Cultural heritage is an intrinsic part of the urban landscape of historical cities. Its tremendous socioeconomic and anthropological value is witnessed by the United Nations’ having included it as part of Sustainable Development Goal 11, which aims to “strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage’.

Despite the global recognition of cultural heritage’s importance and role in enriching our lives, it is under constant menace. The International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) has identified eight different threats, of which urbanisation – manifested through rapid demographic changes and pressures, homogenisation, loss of identity and in the worst case, demolition – is seen perhaps as the most significant.

Because these threats are complex and multi-layered, preservation and efficient management of cultural heritage demand robust information. One such information-gathering tool is geo-information technology (GIT), which through its different forms – remote sensing and graphic information systems (GIS), photogrammetry, and laser scanning – has long been used to document, model and monitor cultural heritage as well as disseminate information about it.

Recent examples include the virtual reconstruction of the Qatari city of Al-Zubarah (Ferwati and El Menshawy, 2021) and the creation of a virtual-reality application for the German town of Duisburg of 1566 CE (Tschirschwitz et al,. 2019). The rationale behind many of these efforts is to help visualise the sites and so understand their previous form, function, and context, as well as re-establish their lost identity.

The case of Shahjahanabad

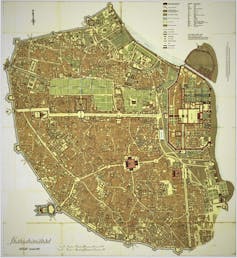

Established in 1648 CE as the capital of the Mughal empire, Shahjahanabad – now known as Old Delhi – was the subject of glowing accounts in the writings of European travellers such as François Bernier.

Today, however, Shahjahanabad is in a state of decay in every sense – physically, socially, and economically. The pressures of development have contributed to the loss of valuable resources, architectural typologies and civic amenities that were once contributing factors to its historic value.

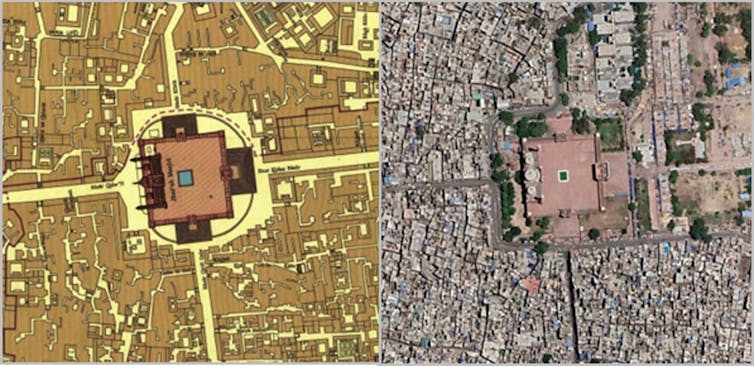

Unlike other cities of Delhi whose historical forms are either untraceable or exist merely as desolate monuments scattered here and there, Shahjahanabad still is a living city. Many of the architectural imprints of the Mughals – including the Red Fort and the Jama Masjid (the main mosque) – have survived the various "planned” and unplanned onslaughts that have befallen the city since its establishment and peak.

Given its density, the city is under constant change, with built heritage continuously being replaced by newer forms. Not only is information on Shahjahanabad’s past obscured and lost, but also the average visitor to identifies the city only with congestion, pollution, and decay, and is completely unaware of the wealthy and glorious city about which travellers such as Bernier wrote.

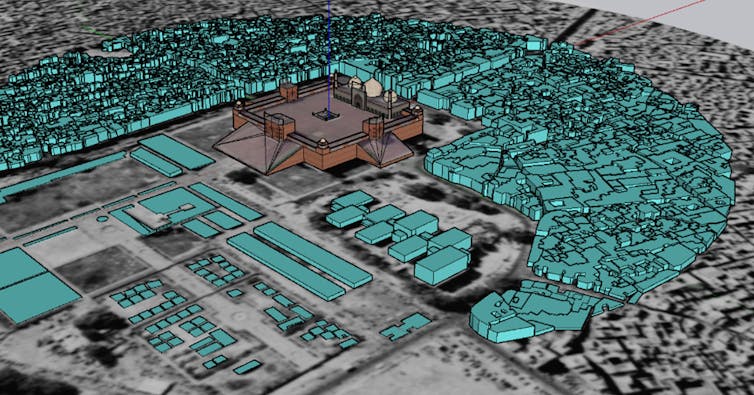

The goal of our ongoing research is to create a digital twin of Shahjahanabad across a spatio-temporal scale. This virtual model would support future conservation efforts, restore the city’s unique identity by creating cultural awareness, and serve as a model for future planning and development.

When photogrammetry meets archival research

Created using geo-information tools such as photogrammetry in combination with archival research, historic maps and survey plans, the digital twin would be a model of Shahjahanabad as it once was. The gaps found in cartographic sources would be filled by extracting spatial information contained in written records, sketches, photographs, and other images. Some of these sources will also be used to construct the virtual 3D model of the city.

Although photogrammetry and laser scanning have been used for creating historic urban environments, modelling dense and “living” heritage areas like Shahjahanabad using these methods takes on a different meaning. The methodology proposed by our research – combining GIT methods with archival research – could be useful for other urban areas that do not have sufficient historic spatial information for modelling the past.

Historic cities at the crossroads

For historic cities in the developing world, there is an urgent need to upgrade infrastructure and housing to improve the quality of inhabitants’ lives. Still, policymakers and planners need to be careful that such vital work does come at the cost of cultural heritage of which cities such as Shahjahanabad are a rich repository.

Digital twins can play a vital role in highlighting the elements of cultural heritage that have been lost to time as well as those that have survived and so need to be preserved for future generations. From spatial-planning perspective, they can present different scenarios to planners and designers for fulfilling contemporary needs while at the same time preserving cultural heritage.

50th anniversary of the World Heritage Convention: World Heritage as a source of resilience, humanity and innovation.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)