Before there was the Cubs-White Sox rivalry we know and love, before one side made fun of the other for its small crowds and the other side clapped back about frat-boy fans drinking in a baseball beer garden, before one catcher punched another in 2006, before interleague play and many years of the exhibition matchups that preceded it, before “Crosstown this” and “Crosstown that,” there was Al Capone.

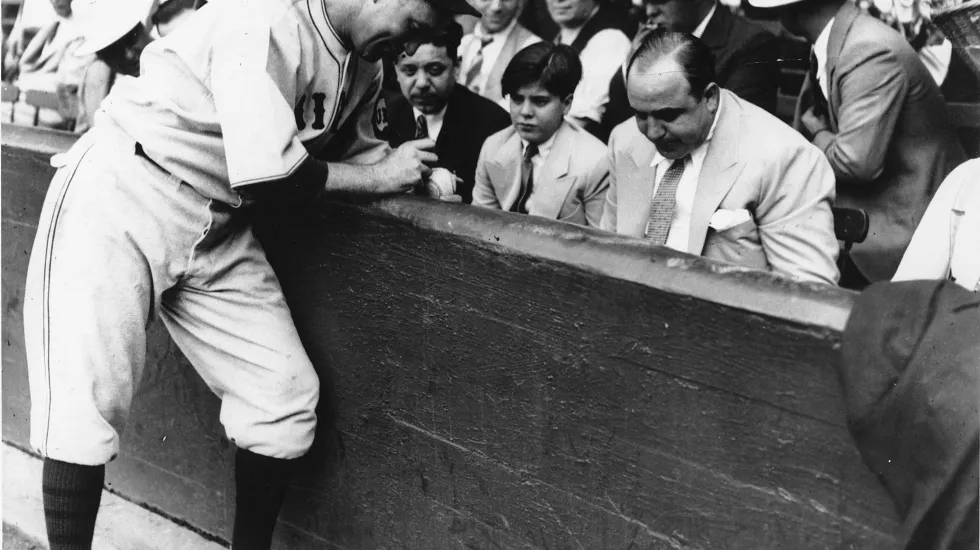

The legendary gangster was in the front row at Comiskey Park for an exhibition between Chicago’s baseball teams in 1931, just a few months before he was convicted on income-tax-evasion charges and sent to prison. Captured in an iconic photo from that day is Cubs catcher Gabby Hartnett signing a ball for Capone’s son as the bad man looks on and bodyguards in white hats sit a row behind. More than 80 years later, one can get lost studying their faces.

So there’s that. Most images chronicling the North-South rivalry’s history aren’t quite as deliciously evocative.

But there has been no shortage of unforgettable stuff since (anybody remember it firsthand?) the Sox beat the Cubs in the 1906 World Series, still the only one of its crosstown-Chicago kind. Maybe, just maybe, there will be another Fall Classic between the teams — Red Line magic — someday. Short of that, we can revel in memories of regular-season moments and outcomes that have counted since interleague play took hold in 1997.

There was Sox slugger Carlos Lee’s walk-off grand slam — the first one in interleague play across the big leagues — off Courtney Duncan at Comiskey in 2001.

“El Caballo!” Ken “Hawk” Harrelson roared into the night.

There was Sox first baseman Paul Konerko homering twice — after being hit by a pitch — as the Sox rallied from an 8-0 deficit to win at home a year later.

And Cubs third baseman Aramis Ramirez belting a leadoff homer off Scott Linebrink in the ninth at Wrigley midway through the 2008 campaign, with both playoff-bound teams in first place.

“Ballgame over!” Len Kasper shouted. “Cubs win!”

Don’t forget then-Sox manager Ozzie Guillen kicking Cubs catcher Geovany Soto’s mask after being ejected in 2011. Fortunately for all involved, Soto wasn’t wearing the mask at the time. And who could forget Cubs catcher Willson Contreras’ sky-high bat flip in 2020? Up, up, up . . . did that really happen?

There have been light moments, such as one hilariously bad Chevy commercial after another in which Guillen and former Cubs skipper Lou Piniella — friendly foes — starred together. And heavy moments, too, such as Harrelson’s tearful 2018 goodbye, ending 33 seasons as a Sox broadcaster, after a game against the Cubs at Guaranteed Rate Field.

“And this ballgame is ovah,” he said.

“Very much, I have enjoyed it. I’ve loved it. And I will never forget it.”

But we can go back further than the beginning of the interleague-play era. Much further.

Through most of the first half of the 20th century, the teams played a yearly City Series against each other. And these weren’t just one-off exhibitions; many of the series, held after the season, were best-of-seven or even longer than that.

Post-World War II, the teams played an annual Boys Benefit game, a midsummer exhibition to raise money for the Chicago Park District’s baseball programs. This lasted until 1972, with the city’s baseball fans always turning out in big numbers.

The in-season exhibitions from 1985 to ’95 weren’t exactly big deals — especially, it seemed, to the Cubs, who somehow managed never to win one. It’s sad but true: They went 0-10-2.

“It seems like the Cubs were always trailing,” Andre Dawson says now. “For us, it was like a spring-training game. Play a few innings, shower up, go home.”

Well, no wonder.

“We took it more serious than the Cubs did,” Guillen says. “Why? Because Tony La Russa demands to go out there and play it right. Even after he was fired [in 1986], it was still his team because he raised us. No matter who we [played] against, it was all about winning.”

One time, in 1994, the Sox even employed a secret weapon: a little-known right fielder by the name of Michael Jeffrey Jordan. With a pair of run-scoring hits — off Dave Otto and Chuck Crim, bless ’em both — Jordan carried the Sox back into what ended as a 4-4 tie at Wrigley. Who says winning NBA Finals MVP is a bigger deal than making the Budweiser Play of the Game?

The pregame interview on the field between giants Jordan and Harry Caray is one of the forgotten gems of the long Cubs-Sox story.

“I want you to know,” Caray said, “I’ve been around this game for 50 years, and this is the biggest thrill of my life, just seeing you in a baseball uniform.”

Answered Jordan: “If I ever develop the skills to be [in the majors], then great. If I don’t, at last I fulfilled a dream of at least trying.”

But once the games got real in 1997, the rivalry really began to flower. It took hardly any time. Whatever it was officially called, it was us vs. you, North vs. South, Addison Street vs. 35th Street, blue vs. black, good vs. bad, bad vs. good. It became a huge deal, often as close as Chicago baseball got to something resembling playoff baseball.

“Cubs-White Sox games are very special,” longtime Cubs radio man Pat Hughes says. “Just the feeling in the ballpark, no matter what side of town, it’s a very special atmosphere.”

Guillen takes it a step further. Then again, doesn’t he always?

“I don’t know about now — maybe it [has gotten] a little less important to the players — but for a lot of years it was amazing,’’ he says. ‘‘I mean, so important for the White Sox and Cubs fans. To me, it’s the closest thing you can be to being in the World Series. It’s that intense. The fans are into it, the media’s into it, all the town is into it. I [bleeping] love it.”

Capone would have loved it, too. We’d tell you how we know that, but then we’d have to . . . you know what? Never mind.

Since the start of interleague play, the Sox have a 70-64 edge — 35-32 on each side of town — over the Cubs. Hmm, that’s pretty close. It certainly doesn’t seem very conclusive. Guess the teams will just have to keep hooking up on the field — four times in 2022, Lord willing — and see how this thing plays out.

No-no? Oh no!

Not to be melodramatic, but Kasper was wracked with fear.

Fear of missing out, more specifically.

“FOMO” wasn’t even part of the lexicon yet, but Kasper was swimming in it. He was 39, in his sixth season calling Cubs games on television, and something huge was developing at Wrigley Field — where Kasper wasn’t.

“Oh, my God,” he says now, “I was going to miss it.”

It was June 13, 2010, and Cubs lefty Ted Lilly was dealing. Sox righty Gavin Floyd was dealing, too. Both pitchers had no-hitters into the seventh inning; Floyd gave up a two-out double in the bottom of the frame to Alfonso Soriano, who would be knocked in by Chad Tracy in a 1-0 victory. But Lilly took his no-no into the ninth — three outs from the first no-hitter at Wrigley since the Cubs’ Milt Pappas spun one in 1972.

The game, on ESPN, was one of 10 or so all season Kasper had off. Watching from home in Glencoe, scorebook in hand, he sat. And fretted. And got up and paced the room. And texted back and forth with broadcast partner Bob Brenly, who was experiencing much of the same thing.

All these years later, Kasper can’t admit it without laughing: As much as he was pulling for Lilly, a big part of him was desperate for a Sox hit.

“I thought, ‘Ted’s going to throw a no-hitter, and it’s going to be the first one at Wrigley since ’72, and I’m sitting at home,’ ” he says. “It’s your team — you root for your guy — but it’s very mixed feelings because when you miss a game like that? It kills you. I was rooting for Ted, but I wanted to call the next no-hitter at Wrigley.”

There is no truth to the rumor Kasper danced in the street after Juan Pierre singled to center leading off the ninth. But, sure, he felt some relief.

“Any broadcaster could understand,” he says. “I was probably 50-50 on what I wanted the outcome to be. At the end of the day, you kind of view the world through your own prism. I mean, 40,000 people at Wrigley, and I’m sitting at home?

“In the back of your mind, you’re like, ‘This can’t happen. I’m not there.’ But you realize your importance — or lack thereof — to the way things are. If you get hit by a bus today, they’re still going to play the game tomorrow.”

Kasper is now the Sox’ radio play-by-play man, in part because he didn’t want to miss out on calling any of the biggest moments. And he has missed his share. He was in the car when Cubs catcher Michael Barrett slugged Sox catcher A.J. Pierzynski in 2006, in the stands for the Cubs’ division clincher against the Cardinals in 2008 and racing for the dugout to assist the Cubs’ radio broadcast when Jake Arrieta no-hit the Dodgers — lucky ESPN — in 2015. Kasper didn’t get to call Jon Lester’s walk-off squeeze bunt against the Mariners in 2016, the 18-inning game (an interleague record) against the Yankees in 2017 or David Bote’s walk-off grand slam against the Nationals in 2018.

But a Wrigley no-hitter against the Sox? An instant classic of that magnitude? The celebration in Glencoe would’ve been bittersweet.

Stone vision

Sox television analyst Steve Stone just might have a better feel for the rivalry with the Cubs than anybody. After pitching on both sides of town, he has been a Chicago broadcasting fixture — first North, then South — since joining the Cubs’ TV booth in 1983.

Stone, 74, has seen it. Lived it. Often loved it. Who better to share his top three moments over decades of crosstown clashes? Here they are:

The Air apparent — April 7, 1994

The teams still were playing a single exhibition game each year, but this one was gigantic because No. 23 — oops, make that No. 45 — was in the Sox’ lineup. Hello, Michael Jordan.

Jordan wouldn’t make it to the big leagues with the Sox, but he was a legend for a day at Wrigley Field, playing right field, batting sixth, going 2-for-5 with a double and two RBI and driving the house wild.

“Fans got a chance to see him in a completely different role,” Stone says. “And then on top of that, he got a couple of hits. The people in the seats were either White Sox fans or Cubs fans, but they were all Bulls and Jordan fans in those days. It was that rare occasion when the entire fandom could cheer one guy. I think that was as unifying a moment as you could have.”

Catchers go awry — May 20, 2006

Everybody remembers it. And if they don’t, they’ve seen the video. And if they haven’t, they’d better get on it right the heck now.

Sox catcher A.J. Pierzynski tags up, beats the ball to the plate and barrels over Cubs catcher Michael Barrett. Then he slaps the plate, gets up and bumps Barrett, who returns the favor with a hard right fist to the face.

“And now all hell breaks loose,” Stone says. “Another highlight.”

Eloy arrives — June 18, 2019

Eloy Jimenez was supposed to hit his first Wrigley home run — and hundreds more — as a Cub. But that was before he was traded to the Sox in 2017. When he finally blasted off there two years later, it was mighty dramatic. In a 1-1 game in the ninth inning, with a runner on, Jimenez broke his bat on an inside pitch from Pedro Strop but still parked a game-winner 10 rows deep into the bleachers in left.

“That was literally a thrilling moment,” Stone says. “The excitement that engendered, I remember it like I was still there watching it.”

Triple play

The words still ring in his ears:

“Along with Hall of Famer Harry Caray and Cubs legend Ron Santo, it’s Pat Hughes at Comiskey Park.”

It was June 16, 1997 — the very first Cubs-Sox game in Year 1 of interleague play across the major leagues.

Hughes, 66, called that one and has called every Cubs-Sox game since. But there has been no topping the first time, which came in his second season on Cubs radio at the tender-ish age of 42. The most memorable part about it? His boothmates.

“You have to kind of stop sometimes and say, ‘What am I doing here? How did I get here? How did I get in the same booth with Ron Santo and Harry Caray?’ ” he recalls.

The game itself was interesting enough. It was, after all, the first crosstown matchup that counted since the 1906 World Series. But the Cubs were a bad team, having started 0-14 en route to a last-place finish. The Sox were uninspiring and would, a month and a half later, cry uncle with the infamous White Flag trade.

The Cubs won 8-3 as Kevin Foster outdueled Jaime Navarro, who allowed seven earned runs in the first three innings but still pitched into the eighth. Ryne Sandberg and Brian McRae each had three hits as a crowd of 36,213 looked on.

But the superstar of the show was, as Hughes saw it, the 83-year-old treasure seated to his left. Caray had the day off, with Sox TV partners Ken “Hawk” Harrelson and Tom Paciorek handling the call on WGN, but he wasn’t one to stay home and miss a good time. On such an occasion, Hughes was delighted to have a third man in his booth. Caray — who would die eight months later — was one of his favorites.

“Harry was an old radio man from his days in St. Louis, so he always loved to join Ronnie and me,” Hughes says, “and I was thrilled to have him in our booth, no matter if they were playing the White Sox or anybody else.

“But what I remember about that day is Harry Caray having the time of his life. Every time the Cubs would score, there would be Cubs fans there cheering and Harry would laugh and bellow out in delight, ‘Listen to this crowd!’ And he just had a great time. That’s the most vivid memory I have of the Cubs-White Sox series, the thrill that I had to work with him.”

‘A pride deal’

The most amazing thing about Tony La Russa as the Sox’ manager isn’t that he returned to the dugout at 76 years old. No, it’s an older story than that. Often forgotten but still kind of wild: When La Russa was hired by the Sox the first time around, in 1979, he actually replaced a player-manager.

That would be Don Kessinger, who forever might be the last person to serve in that dual role for an American League team.

But Kessinger, now 79, is much better known for his time — from 1964 to ’75 — as a Cubs shortstop. For most of that stretch, he met the Sox on the field once a year in what, from 1949 to ’72, was known as the Boys Benefit Game. Held at Comiskey Park or Wrigley Field, the benefit game was a midsummer exhibition and fundraiser for the Chicago Park District’s baseball leagues.

“Back in the day, we didn’t play each other at all other than that because the Cubs trained in Arizona and the White Sox trained in Florida, so the benefit games were really a big deal,” Kessinger says. “Certainly, they were a bigger deal than we, as players, needed them to be. The games didn’t count, but you had so many fans at the games — in pretty equal amounts [supporting] each team — and, I’m telling you, they were serious about whom they wanted to win.”

The players were serious, too. Pretty serious, anyway.

“We’d try to win the game,” Kessinger said, “and they’d try to win the game. I think it was a pride deal, to some extent — and certainly the benefit for the city was very good — and there was some pressure to win it because of the fan involvement. But it’s not like it was the World Series. Then again, what would I know about the World Series?”

Ozzie Guillen goes commercial

Andre Dawson hardly could believe the sound. What kind of person made that kind of racket? Did it ever shut off? Did that mouth ever stop moving?

It was during batting practice at Comiskey Park on May 18, 1987 — Dawson’s first “Windy City Classic” since signing with the Cubs — that he first laid eyes and ears on young, chirpy and sometimes hilarious Sox shortstop Ozzie Guillen.

“I thought, ‘Who is this clown?’ ” Dawson says. “But he came up to me and introduced himself, and I liked that.”

If there’s such a thing as the loudest person in the history of the Cubs-Sox rivalry, it only can be Guillen. He played when the Sox almost always won, even though the games didn’t count in the standings. He later managed the South Siders for 11 seasons, during which the rivalry was at its fiery best. He talked, swore, insulted, swore some more — and that was before he got around to ripping the hell out of a not-yet-renovated Wrigley Field.

“It’s 1000% better now,” says Guillen, 58.

Yeah, well, everybody knows that by now. But not everybody knows these five things about Ozzie:

1. He wasted no time humiliating himself: Guillen was the American League Rookie of the Year in 1985, but on April 29 of that year, he was still a relative nobody. And then he spotted the reigning National League MVP — none other than the Cubs’ Ryne Sandberg — in the visitors’ dugout at Comiskey.

The Cubs were about to take the field for batting practice. Guillen, a really big fan, couldn’t pass up the chance to say hello.

“Hey, Jim!” Guillen yelled as he approached. “Jim Sundberg!”

Sandberg looked at him as though he had two heads. Sundberg was a longtime AL catcher who, ironically, would become Sandberg’s Cubs teammate in 1987.

“I just got so excited, so nervous to meet him,” Guillen says. “I said, ‘Oh, I’m sorry — Ryno!’ That was one of my most embarrassing moments in baseball.”

2. Home cooking could be a very bad thing: It’s possible no Cubs manager has wanted to beat the Sox as much as Guillen wanted to beat the Cubs. With Dusty Baker and then Lou Piniella in the other dugout — and working on the side of town Guillen swore got more love and attention from the media — Guillen, even after winning the 2005 World Series, wanted to be recognized.

“I wanted to be the best [bleeping] manager in town,” he says, “at least for a week or a weekend.”

Guillen was 23-23 against the Cubs as manager. Oh, well. Win some, lose some?

“Man, that series was huge,” he says. “I liked to win, especially against the Cubs.

“We had rules in my house: If we beat the Cubs, we eat at a restaurant; if we lose, Mom has to cook. Because I don’t want to go out and be around people if we lose. We lose to anybody else, I’m a miserable man. We lose to the Cubs, you can triple it.”

3. He has a regret … kind of: Guillen really blew it in the bottom of the eighth inning at Wrigley on May 19, 2007. With the bases loaded, he went to the bullpen and got lefty Boone Logan. Piniella responded by sending in righty slugger Derrek Lee — who wasn’t expected to be available — to pinch-hit.

Bye-bye, baseball. Grand slam. The Cubs scored six in the frame for a comeback victory.

Guillen isn’t proud of the answer he gave a reporter who asked after the game why he’d made the move to Logan.

“Do I remember what I said? Yeah, I remember,” he says. “I said, ‘Because I’m the [bleeping] manager, that’s why I made it.’ That was not the best answer. Maybe I shouldn’t have said that.”

4. He has no regrets about this: On one rainy day at Wrigley, Guillen’s criticisms of the ballpark had blown up into a bit of a controversy. Guillen thought local media were full of it by not agreeing with him publicly. When it was time for his daily pregame briefing — the rain picking up — he insisted on doing it in the dugout, even though it wasn’t big enough to provide cover for all the reporters and cameras.

“I say to the media, ‘You want to say the same thing as me, but you don’t have the guts,’ ” he says. “It was a terrible place for them to work.

“Half of them were soaking wet. I told them, ‘See? If this happens at another place, you’re not so wet.’ Some guys laughed, some guys hated it, but I made my point.”

5. The best part of the rivalry: Believe it or not, Guillen says he looks back most fondly on all the truly ridiculous commercials he did with Piniella. Recalling the ads — fishing, rapping, pretending to race cars — still cracks him up.

“All the commercials I did with Lou, all of it was amazing,” he says. “It was the funniest part of being a manager in town. I would just show up and look at Lou’s face and just die, man. He made the funniest faces when he tried to act. I love Lou Piniella.”

Brawl over the call

The day after Cubs catcher Michael Barrett punched White Sox catcher A.J. Pierzynski at the plate in 2006, there almost was another brawl at the Cell.

No, not between the crosstown rivals. Between Pierzynski and the Sox’ then-TV analyst, Darrin Jackson.

Let’s take it from the top. The famous fight was during a telecast on Fox, with Jackson working alongside play-by-play man Thom Brennaman. Because it was a national game, Jackson’s intent going in was to show no bias. But he wasn’t about to blame Pierzynski’s face for hitting Barrett’s fist.

As Jackson remembers it, Brennaman asked repeatedly about Pierzynski’s role — barreling into Barrett, slapping the plate after Barrett fell, bumping into him again after both rose to their feet — wanting to know if the punchee had been the instigator.

“Finally,” Jackson says, “I was like, ‘Thom, it’s possible.’ ”

Jackson had been involved in the previous most-famous moment in modern Cubs-Sox history: the Jordan game in 1994. Most long have forgotten — if they ever knew — that Jackson was the man Jordan drove home on his first hit in that exhibition game at Wrigley Field.

“What a memory,” Jackson says. “What a conversation piece for my involvement.”

But now, 12 years later, Jackson was at the center of the rivalry’s new most-famous moment. An article had been written that portrayed Jackson as having put the onus for the Barrett incident on Pierzynski.

So, again, the day after: Jackson entered the Sox’ clubhouse.

“A.J.!” he yelled, approaching.

According to Jackson, he was met with an outpouring of F-bombs. Aside from that, Pierzynski said he wouldn’t be speaking with him.

“I said, ‘First of all, don’t you ever talk to me like that again. Secondly, you owe me an apology. I defended you,’ ” Jackson says.

But Pierzynski was all lathered up, and it almost got ugly. Fortunately, it didn’t. Jackson moved to Sox radio in 2009 and has been there ever since. More than 20 years in as a Sox broadcaster, he is a South Side fixture and part of a small fraternity, so to speak, of prominent figures with baseball roots on both sides of town.

A day-after fight might have changed all that. It would have been a disaster. But Jackson and Pierzynski were able to squash it. Good thing, too.