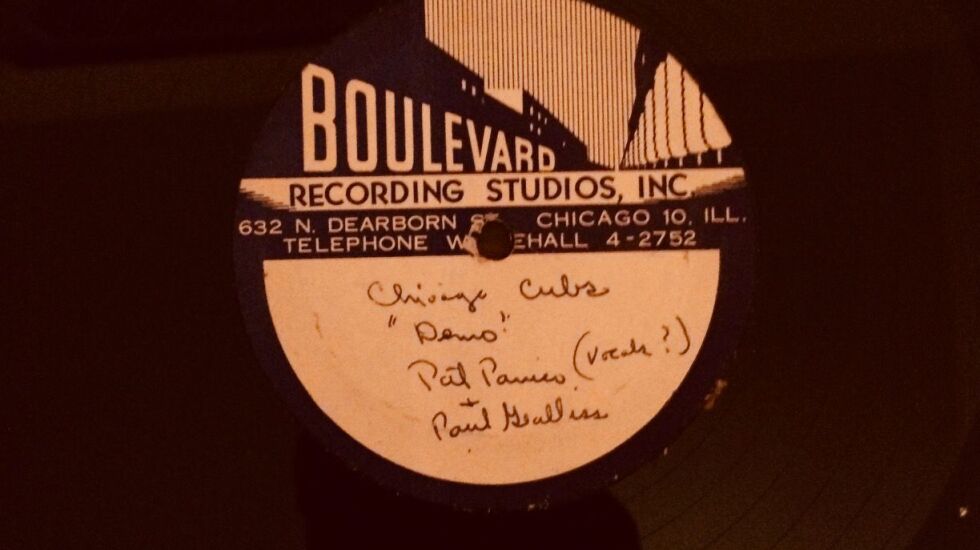

While sorting through his grandfather’s vast record collection in 2015, Rob Sarwark found a mysterious vinyl record labeled “Chicago Cubs Demo.”

The record bore the names of his grandfather, Pasquale “PJ” Panico, and a late family friend, Paul Gallis.

A year later in 2016 — just as the Cubs secured a World Series spot — Sarwark played the record after his grandfather’s passing and discovered a forgotten Cubs booster song, recognizing his grandfather’s voice.

Sarwark collaborated with producer Steven Serra in 2017 to release multiple versions across music streaming platforms. It has been waiting for a true champion to revive it ever since.

“Songs are like houses,” Sarwark said. “They’re not really homes until somebody is living and thriving in them.”

Now, the song — dubbed “Come Out to Wrigley Field (The Home of the Cubs)” by Sarwark and his family — will be revitalized by Chicago jazz musician Sam Fazio, who’s set to perform it at a pregame event at Gallagher Way on Wednesday.

Fazio, a longtime family friend of the Panicos, has performed at pregame and halftime shows for Chicago sports teams for about a decade and recently started playing Cubs pregame shows around Wrigley Field. Given the song’s connection to the location, Fazio said it felt right to reach out.

“The stars just all aligned,” Fazio said. “I was singing [at Wrigley Field], I reached out to Rob, I said ‘Let’s make this happen.’”

Despite the song’s resurgence, the official Cubs song remains “Go Cubs Go,” and the team has no plans to adopt a new song, according to Julian Green, vice president of communications and community affairs for the Cubs.

“We have generations of Cubs fans, so [we’re] not surprised there are diehards like Fazio who would want to share his love of the Cubs through this tribute to the Panico family,” Green said.

Fazio says he feels a connection to Panico as a Chicago-based musician who splits his time between pursuing his passion for music and a career to support himself.

Panico, who was born and raised in Little Italy, was the father of five children, one of whom was Sarwark’s mother. A World War II veteran, Panico was a Streets and Sanitation worker for the city by day and a musician by night, according to Sarwark.

“He didn’t retire until he was 87,” Sarwark said.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Panico played accordion and sang as part of a trio called The Fascinators. Sarwark, who now co-owns the record label Tiki Core Records, said he inherited his grandfather’s love of music and recalls having jam sessions with him during the holidays.

Sarwark described his grandfather as “very Chicago” in the way that he spoke, adding Panico often used jazz slang and called people “cats.”

Also named on the uncovered record was Gallis, another Chicago native and World War II veteran who came up in the city’s music scene. His son, Jimmy Gallis, said his father was a musician who went on to work as an independent record promoter.

“My dad was just one of those guys who was very infectious,” Gallis said. “His goal in life every day was just to make people smile.”

Panico and Gallis were friends who met through the city’s tight-knit music scene, Jimmy Gallis said. Growing up, Gallis knew Panico as “Uncle Pat.”

When it comes to “Come Out to Wrigley Field,” Gallis said his father likely worked on writing the lyrics while Panico focused on the accompaniment.

With punny baseball lyrics like “Come on and pitch your worries away” and “We strike our troubles and woes,” Gallis said his father’s stint as a standup comedian likely came out while writing the song.

Gallis says he’s a lifelong Cubs fan and so was his father, but the same wasn’t true of Panico.

“He was a Sox fan,” Sarwark said of his grandfather.

“Come Out to Wrigley Field” was likely recorded between 1960 and 1965 as a Chicago Cubs jingle. As a musician who needed to make a living, Sarwark said, his grandfather likely saw the song as an opportunity and put his baseball loyalties aside to produce the record.

Sarwark says he hopes his grandfather doesn’t mind the song’s revival and thinks if he didn’t want anyone to ever hear it, he would’ve just thrown the record away.

Multiple members of the Panico and Gallis families plan to come out for the Aug. 2 performance.

“I hope [the song] adds to a feeling of being part of something, being from Chicago and having pride in the city and just everything that goes along with baseball in terms of it being the national pastime and something that brings joy to people,” Sarwark said.