Crimes of the Future is not body horror.

Though that term has long been associated with the films of Canadian writer-director David Cronenberg — and works like gangbusters as a marketing pitch — it’s never accurately described his work, aesthetically or philosophically. In his new film, spectators gather to watch a man covered in ears writhe to electronic music. “He’s a better dancer than a conceptual artist,” sneers one critic.

It sounds a bit like how Cronenberg himself might critique the sub-genre. It’s also about as far as body horror can take us.

Cronenberg’s movies obsess over flesh, transforming it, doing unspeakable things to it. But for this filmmaker, the body is merely the raw material, the visual goo from which he builds his stories. It’s a means to an end.

His true fixation is on the intangible inside. He’s obsessed with ideas. And so are many of his characters, who dwell as much on art and the creative process as they do on the body.

Think of Bill Lee, the novelist in Naked Lunch. Or Allegra Geller, the designer of bio-organic virtual reality games in eXistenZ. Or even Jeff Goldblum’s scientist Seth Brundle in The Fly, who approaches his experiments like an artist looking for “the poetry of the steak.”

But in Crimes of the Future, Cronenberg puts artists and the art world into the center of the story and builds the world around them. In the film, people have become so disconnected from their body they can no longer feel pain (except, for some, in sleep). Saul Tenser (Viggo Mortensen) is a performance artist. His body won’t stop producing new bodily organs, and so as an act of defiant rage, he has teamed up with life and creative partner, Caprice (Lea Seydoux), to remove the organs during public performances that electrify audiences.

Among those audiences are Whippet (Don McKellar) and Timlin (Kristen Stewart), administrators of a secret government bureau that seeks to register and catalog all the new organs people seem to be growing. Saul is also an undercover informant, meeting by night with Detective Cope (Welket Bungué), an operative of the newly formed New Vice Unit tasked with crushing subversive movements that are ”evolving away from the human path.” The story heats up when Saul is approached by one such subversive, whose son Brecken (Sozos Sotiris), a mutant capable of digesting plastic, has been murdered by his own mother.

Per the title, the crimes of concern are of the future, not those actually committed in the present — two brutal murders by drill cause barely a ripple. But the crimes that cause anxiety for the establishment are theoretical, abstract crimes: the threat of evolution, of human bodies becoming less human, of ideological threats. The horror is not in the body but in the anxiety that the very idea of body has lost meaning. If the body can be cut open in public for spectacle, if it can eat and digest trash cans or be made to feed on toxic waste, is it even a body at all?

The Cronenberg aesthetic universe

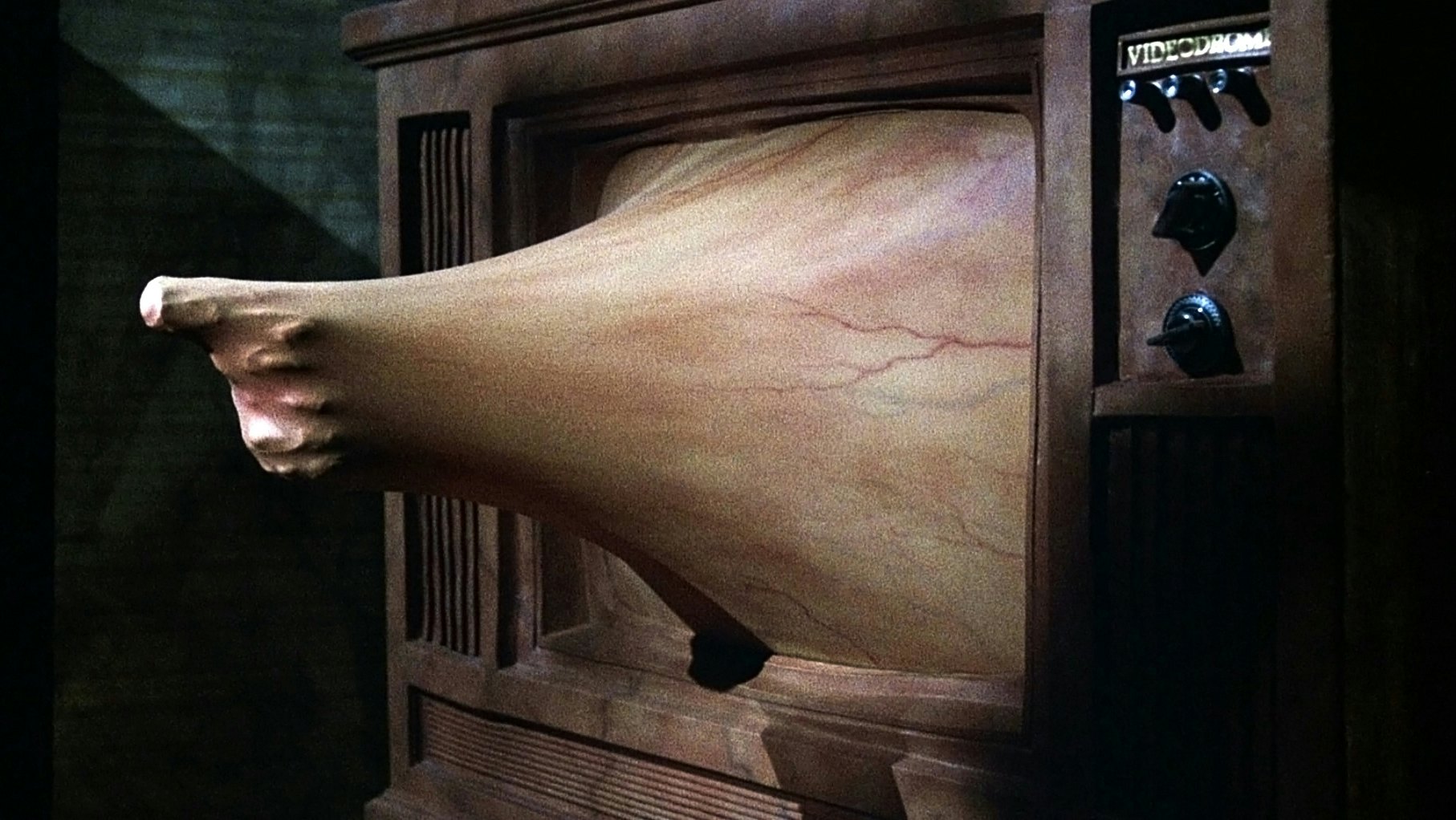

Crimes of the Future reflects so much of Cronenberg’s previous work that it feels like an extended universe. Not one of characters and events but of his aesthetics, his obsessions, and his warring, nested ideas. Brecken’s white, acidic saliva recalls Jeff Goldblum’s Fly digestive fluid. The RipLock — a fleshy zipper installed into Saul’s abdomen to better spy on his exciting new organs — calls to mind James Woods’ Videodrome organ. The knobby, unsettling technology (courtesy, as usual, of production designer Carol Spier) is reminiscent of the bone gun and control pods of eXistenZ or the creatures and typewriters of Naked Lunch.

Because Crimes Of The Future has so much in common with previous work, the differences glisten and drip with meaning. It suggests a culmination, a reimagining but also a re-aligning — and maybe even a betrayal.

Cronenberg’s films usually begin with an inciting incident that launches the hero’s obsession and physical transformation: the telepod experiment that fuses Brundle with a fly; Will Lee killing his wife and moving to Interzone in Naked Lunch; Max Renn exposed to the Videodrome signal. As the characters become energized, transformed, and even inspired by their new circumstances, they pull the audience into a complex, paranoid world. We learn about it as they do.

In most of Cronenberg’s work, a vibrant couple — Woods and Debbie Harry in Videodrome; James Ballard and his icy wife Catherine in Crash — finds themselves thrown together and then torn apart by new ideas. As the ideas grow within them, the relationship becomes an opposition. Cronenberg’s cerebral obsessions manifest as sexual and emotional betrayals. He depicts the war of ideas through the modes of intimacy and break-ups.

In a pointed break from his previous films, Cronenberg begins Crimes at a later point in time than usual. Caprice describes her Cronenbergian meet-cute: being dazzled by Saul after performing surgery on him. Only here, that’s ancient history. Saul has for some time been living with a body in rebellion. He has already adapted his rage and turned it into art. The inciting incident of the movie — the murder of Brecken, an act of maternal filicide on the Aegean sea that suggests the tragedy of Medea — does not happen to him. That act of violence does not change Saul’s body. But it will change his ideology.

Just as soon as we’ve met Saul and Caprice, as well as the bureaucrats Whippet and Timlin, they are already transforming each other’s ideas, and we are racing to catch up in a setting that feels deliberately obscure and confusing, full of hidden truths and subtexts. To quote Adrian Tripod, the lead in Cronenberg’s original 1970 Crimes of the Future, which also featured a man growing and cataloging new organs, “Their purposes are entirely opaque to me. As are the purposes of so many others.”

Ideas are contagious, more perilously so than disease. (As Masha says about Videodrome, “It has something you don’t have — a philosophy. And that’s what makes it dangerous.”) The panic in Crimes of the Future is not that bodies are changing, but that people have new ideas about changing their bodies. The authorities see these ideas as a doorway to utter chaos. “It's pathological. It's not healthy. It's a breakdown of the system. An organism needs organization. Otherwise, it's just designer cancer,” claims Caprice.

Cronenberg has always depicted a paranoid view of human relationships, from the triple agents of Interzone in Naked Lunch to Max’s closest friend revealing himself to be his most dangerous enemy in Videodrome. In Crimes of the Future, the betrayals are fractal-like, one inside the other. Saul’s insides betray him by growing new organs that he surgically removes. In turn, he betrays a community of futuristic thinkers by being a New Vice informant. (It’s not the first time Cronenberg has turned Viggo into a tattooed undercover agent, though in Eastern Promises his ink was visible on the outside.)

Meanwhile, Whippet is both an employee of New Vice and the leader of the subversive criminalized organization behind the Inner Beauty Pageant. In the climactic autopsy, the inside of Brecken’s body is a revelation, but a revelation of betrayal. We are expecting to see nature’s new take on the human digestive system. Instead, we see sabotage. Kristen Stewart’s Timlin, it seems, has made the body look like a hacked surgery instead of a miracle. A betrayal against the awe-inspiring truth.

Of betrayal and transcendence

Crimes of the Future deploys Cronenberg’s usual crisp materialist aesthetic — perfectly linear, perfectly clear, composed, and paced as if by surgical steel. But as shot by new-to-Cronenberg cinematographer Douglas Koch, it is arguably his most beautiful. The lighting evokes Renaissance paintings, depictions of The Passion. The colors, and the halos and shadows around Viggo Mortensen’s head, approach the mythological. The aesthetics suggest the ultimate betrayal in Crimes of the Future might be against the filmmaker’s long-held beliefs themselves. A betrayal around the possibilities of transcendence.

Videodrome, The Fly, The Dead Zone — these movies all end at the exact second the main character takes a bullet, his point of view snuffed out. eXistenZ mocked the idea of transcendence, ending in the reveal of a game called transCendenZ from which we may never escape. A false transcendence. An impossibility.

Videodrome, in fact, rests on a vehement denial of transcendence. Cronenberg originally planned to end the movie in a kind of orgiastic afterlife — Max and Bianca and Nikki all in the red Videdrome world, intertwined with glorious new sex organs. But the filmmaker’s own hard-core atheism prevented him from depicting the consciousness of humans who had died. The bullet must end the experience because Cronenberg does not believe in an afterlife.

But Crimes of the Future doesn’t end with a death. It is a movie about ideas and inspiration rather than the limits of the body. And therefore there is the possibility of transcendence beyond our philosophical limitations or the limitations of our life on earth in these bodies.

Just like Joan of Arc taking communion to prepare for her execution at the end of Theodor Dreyer’s Passion of Joan of Arc, Saul risks death by biting into the toxic candy bar. Cropped, black and white, looking upwards in beatific ecstasy in an exact reflection of Dreyer’s saint, Saul leaves his body and accepts the truth of himself. This is the real shock: It is a spiritual moment. The glimmer of a soul.

Seeing Saul in this perfect reproduction of Joan, we have to imagine what she imagined: that her body’s death and destruction would not be the end of her. This is the crime Cronenberg commits, the sin of suggesting transcendence. Maybe not going so far as to claim a literal belief in an afterlife — but maybe through ideas, through evolution, through the single tear of a transforming artist, there is some future beyond the body.

Crimes of the Future is in theaters now.