John Ure, born and raised in Adamstown, was a NSW Police detective in the Hunter throughout the 1970s and early 1980s. Here's his latest crime file.

Thursday, November 2, 1972 started much the same as any other day for Neville Parker, a maintenance engineer at the then fully-operational Wangi Power Station, but the day was to take a dramatic turn.

Shortly after lunch Neville set out on a routine inspection of the Number 3B Boiler and, for the first time since March 1971, climbed into the "dead space", a chamber above the boiler which served as further insulation to the main boiler.

Although the inside of this chamber was not exposed to direct flame, it could reach a temperature of 2500 degrees. He made his way along its length, through the thick 100mm layer of dust and, as he reached the other end, was shocked to see what looked like a complete human skeleton lying in the dust, just below an access hatch with the lid partially removed.

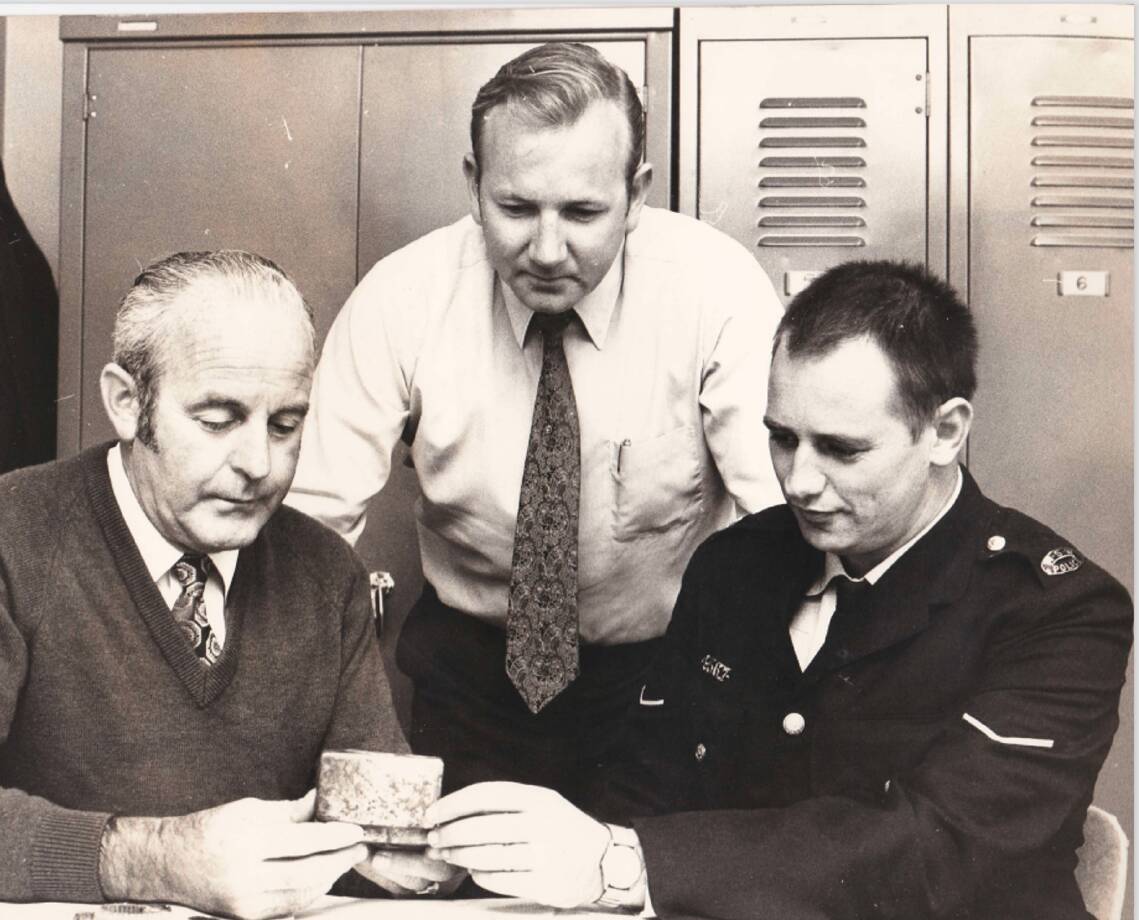

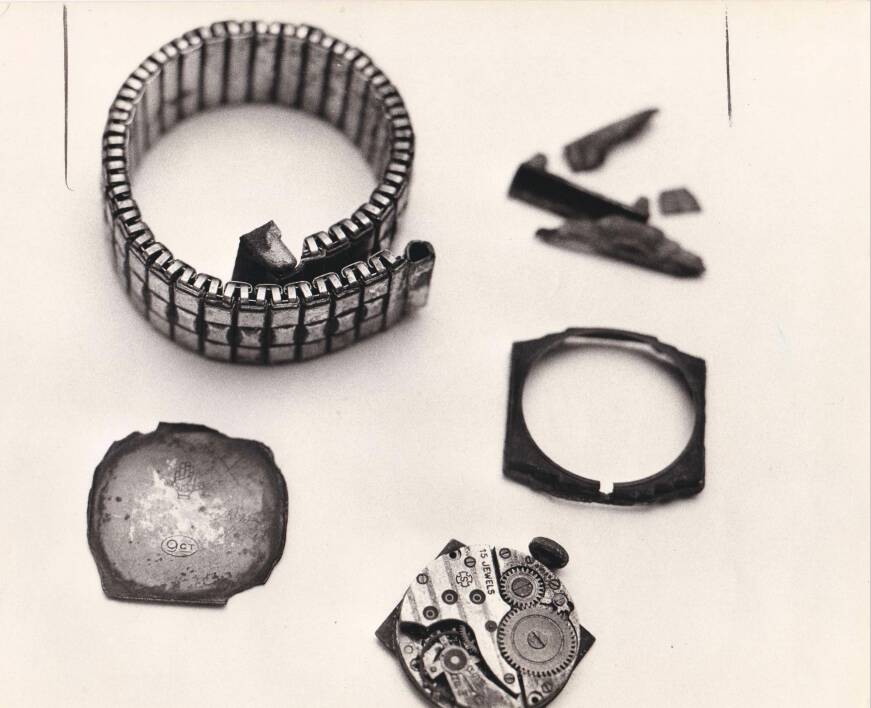

Detective Sergeant Max Jacobson, my boss at Toronto, and I were there in quick time. We confirmed that it was a human skeleton and also found a few personal items in the dust - a man's wristwatch, a chrome tobacco tin, a metal arm band and the remnants of a belt.

Detective Brown of the Newcastle Scientific Section photographed the scene and took the bones for examination. Doctor John Raschke, government medical officer, would confirm that the bones were human and that there was no apparent damage to the skull or any of the bones.

So, who was this person? How and why did he, or she, find their way into the dead space? Was it murder? Was it suicide? Or was it just an unfortunate accident?

There were no records of missing persons in the area, however Constable Eddie Gill - the sole officer at Wangi Wangi Police Station - recalled that about 18 months earlier Victor Evans, a former local resident, had reported to him that his neighbour, Arthur Lawrence Sneddon, an alcoholic who had spent time in Morisset Hospital as an inebriate, had banged on his door in the middle of the night in a frantic state and blurted out: "There's two blokes chasing me, they're going to get me. Here they are coming through the gate now".

Mr Evans confirmed that there was nobody else in the vicinity and was also satisfied that Arthur was hallucinating. He formed the opinion that he was suffering from the DTs [delirium tremens], then encouraged him to go back inside to sleep it off. He did not see Arthur again.

Arthur, whose mother lived in Sydney, was not reported as a missing person as he frequently went wandering off for a few days or weeks. So, there was a strong possibility that the skeleton was Arthur Lawrence Sneddon, but how to prove that to the satisfaction of his family and the coroner?

There were some very small markings and numbers on the inside of the back of the watch. This was before throw-away watches; if your watch wasn't working you took it off to a watchmaker for repair.

I knew that watchmakers generally recorded their individual mark on the inside of the back of the watch during repair, so off I headed into Newcastle to track down the watchmaker who inscribed these markings and, after a few false starts, to Whitakers Jewellers where watchmaker Hugh Dare identified his mark and showed me a job-sheet where the watch was booked in under the name of Sneddon, of Wangi.

Detective Sergeant Jacobson and I travelled to Cessnock, where Arthur Sneddon's mother was now living, and she identified the tobacco case, armband and the watch as having originally belonged to her late husband, who had passed them on to their son Arthur. Her sister Enid was also able to identify the items.

On April 26, 1973, Newcastle Coroner Reg Radford found that Arthur Lawrence Sneddon had died at the Wangi power station, "but when and by what means he died, the evidence adduced does not enable me to say".

And that shall remain a mystery. We know that Arthur had a working knowledge of the power station but the reason for him climbing into that remote space died with him.

Since the early 1950s the Wangi Power Station has dominated the landscape at the south-western end of Lake Macquarie. Operating from 1956 to 1986, it played an important role in keeping the lights on in NSW during the critical power shortages in the 1950s and 1960s and at one time was the largest power station in the state.

It was heritage-listed in 1999 and hopefully will one day be repurposed to again bring life to this imposing, historic building. Perhaps the tale of the skeleton in the dead space will figure somewhere in its new life.

Put Down That Weapon

Sticking with crime, Newcastle Police posted this on Facebook this week: "We have seen an increase in firearms offences involving realistic Gel Blaster firearms. Gel Blaster weapons are illegal in NSW and are treated as real firearms when police are considering charges and in the eyes of the court."

WHAT DO YOU THINK? We've made it a whole lot easier for you to have your say. Our new comment platform requires only one log-in to access articles and to join the discussion on the Newcastle Herald website. Find out how to register so you can enjoy civil, friendly and engaging discussions. Sign up for a subscription here.