The North Park Village election site, at 5801 N. Pulaski Road, is tucked into one of the hidden jewels of Chicago, a 155-acre bucolic preserve born in the early 1900s as the Municipal Tuberculosis Sanitarium.

On Tuesday, Election Day, a ribbon of campaign signs for candidates for mayor, City Council and police districts lined most of the driveway — about 1,000 feet — from Pulaski to near the steps of the administration building, where voting was taking place in a majestic room at the end of a covered portico.

Scotty Goldblatt, 59, a musician who lives in West Rogers Park, just cast his ballot, and as he was leaving the complex, I asked him whom he voted for and why.

Of “the issues that are important,” Goldblatt said, “No. 1 is crime.”

Though Goldblatt declined to say whom he backed for mayor, he summed up the major issue driving this election and the April 4 runoff: public safety.

With the defeat of Mayor Lori Lightfoot, voting goes into round 2.

Former Chicago Public Schools CEO Paul Vallas faces off April 4 against Brandon Johnson, a Chicago Teachers Union staffer and Cook County Board member.

The runoff contest will be in large part a referendum on their approaches to crime.

They will wrestle with the city’s most complicated problems and root causes of pervasive crime, including poverty, lack of housing, health care and racism. The history of Chicago police brutality — and the availability of guns — will remain a challenge.

All the candidates for mayor knew voters were fed up with crime and addressed it.

Vallas, running with the support of the Fraternal Order of Police, the cops’ union, leveraged the crime issue to become a front-runner, finishing first in the field of nine.

Crime is “overwhelmingly the issue voters are very concerned about,” Joe Trippi, the top strategist for the Vallas campaign, told me Friday.

Trippi called in while I was interviewing Vallas campaign manager Brian Towne in Vallas’ West Loop brick-walled campaign headquarters.

Towne said crime was “the No. 1, 2 and 3 issue” and “it all kept coming back to crime in all the neighborhoods.”

The Vallas campaign boiled it down to this tag line on his closing ads: Vallas is “the Democrat who will put crime and your safety first.”

The election will also produce a potentially new significant factor when it comes to policing in the city, perhaps launching those who will become the next generation of elected leaders in the city.

For the first time, voters are electing 66 police district members, three from each of the 22 police districts. These spots have provided something very rare in the city for people interested in politics: an entry-level elected position where every seat is open with no incumbent.

The Chicago mayor — and the 50 City Council members — will have to deal with 66 new players now when it comes to policing, a factor not discussed much in the campaign.

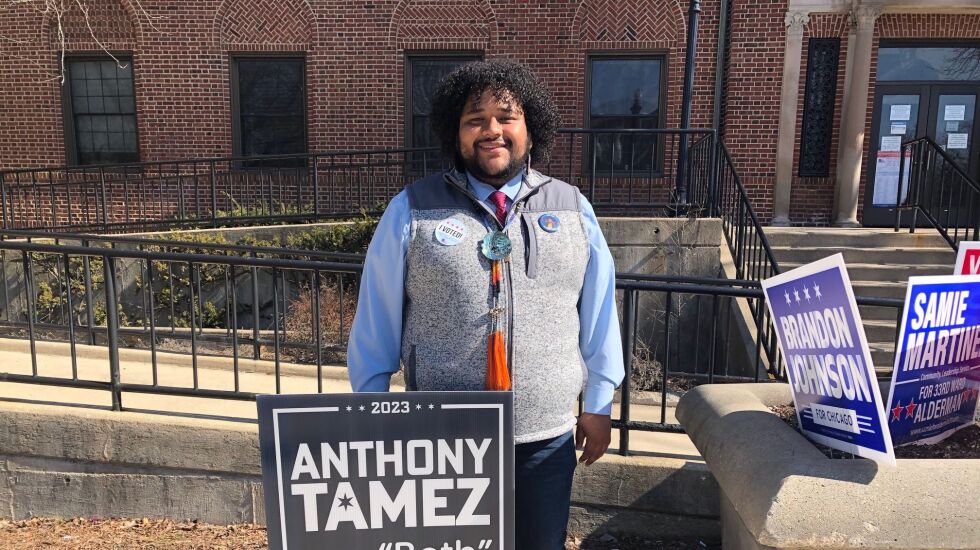

At the age of 23, Anthony Tamez is probably one of the youngest people on the ballot. Tamez, an Irving Park resident, ran for a seat on the 17th Police District council, part of a three-person slate backed by a variety of progressive organizations.

According to unofficial returns, Tamez won his seat.

Tamez, a First Nation Cree, is a program contractor for the Center for Native American Youth. He said he voted for Johnson for mayor and was at North Park Village looking for last-minute votes when we talked.

“I believe that district council positions are going to be an outlet for community voice and to allow the communities to talk with each other and to understand how we as a community get to keep us safe,” Tamez said.

How powerful these councils will become — and how they interact with the mayor and City Council — remains to be seen. Said Tamez, “I think the most significant power that comes with the seat is just the platform we are given.”