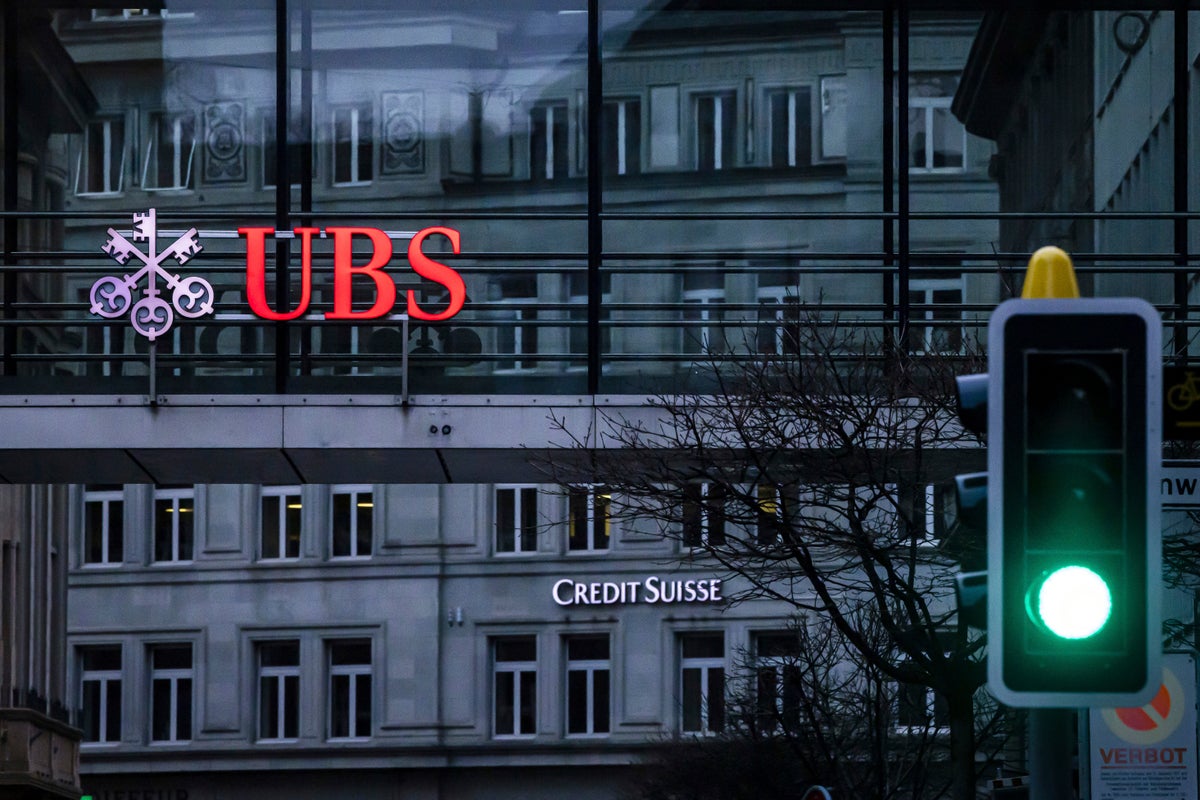

The UBS takeover of embattled rival Credit Suisse has shaken Switzerland’s self-image and dented its reputation as a global financial center, analysts say, warning that the country’s prosperity could grow too dependent on a single banking behemoth.

The uncertain future of a union of Switzerland’s two global banks comes at a thorny time for Swiss identity, built nearly as much on a self-image of finesse in finance as on know-how with chocolate, watchmaking and cheese.

Regulators who helped orchestrate the $3.25 billion deal have a lot on their plates as UBS checks the books of its rival, cherry-picks the parts it wants and dispenses with the rest.

“The real question is what’s going to happen, because we’ll now have a mastodon — a monster — that will be increasingly too big to fail,” said Marc Chesney, a finance professor at the University of Zurich. “The danger is that over time, it will take more risks knowing that it is too big for the Swiss state to abandon it.”

After studying the numbers, he said, the total value of exotic securities — like options or future contracts — held by the merged bank could be worth 40 times Switzerland’s economic output.

“Over time, UBS will control the Swiss state, rather than the other way around," Chesney said.

The neutral, prosperous country of about 8.5 million people enjoys the highest gross domestic product per capita of any country its size. Switzerland's relatively low-tax and pro-privacy environment draws well-heeled expats, and it regularly ranks among the most innovative countries. Over generations, it has become a global hub for wealth management, private banking and commodities trading.

That climate also has bred a reputation as a secret haven of billions in ill-gotten or laundered money, with the Tax Justice Network ranking Switzerland second only to the U.S. in financial secrecy.

That was on display this week when a U.S. Senate committee's two-year investigation found that Credit Suisse violated a plea agreement with U.S. authorities by failing to report secret offshore accounts that wealthy Americans used to avoid paying taxes.

Such turmoil at the Switzerland's second-largest bank, which also includes hedge fund losses and fines for failing to prevent money laundering by a Bulgarian cocaine ring, made it vulnerable as U.S. bank collapses stirred market upheaval this month.

Now, many conservatives are reviving their calls for Switzerland to turn inward.

Christoph Blocher, a former government minister and power broker of the right-wing Swiss People’s Party, blasted the Credit Suisse-UBS deal as “very, very dangerous, not just for Switzerland or the United States, but the entire world.”

“This has to stop,” he told French-language public broadcaster RTS. “Swiss banks must remain Swiss and keep their operations in Switzerland.”

If Switzerland wants to be a strong financial center, it needs a strong globally significant bank, said Sergio Ermotti, who was CEO at UBS for nine years and will return to help shepherd the takeover.

“For me, the debate nowadays is not ‘too big to fail' — it's rather ‘too small to survive,’" Ermotti said at a news conference this week. ”And we want to be a winner out of this.”

Gregoire Bordier, scion of an illustrious Geneva banking family who chairs the Association of Swiss Private Banks, played down the size of the merged institution, estimating that it would have roughly the same weight in Switzerland as Dutch giant ING does relative to the Netherlands' economic output.

“Rather than arranging the dissection of the last great ‘universal bank’ in this country — and let rival finance companies benefit — it's above all necessary to roll out much greater control measures for the new UBS,” Bordier told the Tribune de Geneve newspaper.

Still, he acknowledged that the combined entity's potential importance within Switzerland was "another question,” saying he reacted to the banks' shotgun marriage, announced on prime-time TV, as if watching “a bad soap opera.”

Critics say the federal government was asleep at the wheel and hadn’t learned from the 2008 global financial crisis.

Blocher’s protégé, Ueli Maurer — who was finance minister until stepping down in December — championed a hands-off approach to banks like Credit Suisse to let them sort out their own troubles.

The Credit Suisse rescue is a stain on regulators and the idea that putting money into a Swiss bank means it’s “rock solid and safe,” overseen by the world's best financial managers, said Octavio Marenzi, CEO of consulting firm Opimas LLC.

“That reputation has gone up in smoke, and it’s very hard to regain that reputation,” Marenzi said. “Unfortunately, a reputation that you built up over years and decades and maybe even centuries, you can destroy really quickly.”

Beyond banking, Switzerland’s image has been unsteady recently, generating debate ahead of parliamentary elections in October.

A web of bilateral deals with the European Union, Switzerland's biggest trading partner, are clouded under a standoff with Brussels. The country's constitutionally enshrined commitment to “neutrality” has angered Western nations that are blocked from shipping Swiss-made arms to Ukraine so it can fight Russia.

Swiss diplomats, who have been intermediaries between Iran and Saudi Arabia since the countries broke off ties in 2016, were absent as China brokered an agreement this month to restore relations between the Mideast rivals.

Scott Miller, the U.S. ambassador to Switzerland who is a former UBS executive in Colorado, upshifted the debate about how the European country interprets its idea of neutrality.

Miller told the Neue Zuericher Zeiting newspaper this month that Switzerland was facing its "biggest crisis since the Second World War” and urged the Swiss to do more to help Ukraine defend itself — or at least not block others from doing so.

Before the bank marriage was engineered on March 19, Credit Suisse was hemorrhaging deposits, shareholders were dumping its stock and creditors were rushing to seek repayment.

Since then, some smaller Swiss banks have reported an influx of deposits from Credit Suisse customers. Staffers face the prospect of sweeping job cuts, though details may take weeks or months to iron out.

The fallout is far from over.

A special session of Parliament next month is expected to discuss the takeover, including “too big to fail” legislation and possible penalties against Credit Suisse managers.

Sascha Steffen, a professor of finance at Germany’s Frankfurt School of Finance & Management, said “having such a huge bank isn’t necessarily bad,” pointing to efficiencies.

But creating a behemoth could make it harder for small businesses to get credit. The way the takeover was done — using emergency measures to tweak Swiss law and shucking the bondholder-shareholder pecking order on losses — has unsettled investors.

“The false marriage that was initiated by the government was something markets don’t really like, particularly when there was no involvement of other stakeholders whatsoever,” Steffen said.

“The attractiveness as a place to invest is definitely damaged,” he said.