Hundreds die each year from workplace-related incidents in Canada. Alberta, in particular, has seen its fair share of recent deaths, like the man who was killed at a construction site in Cochrane last September, and the oilsands worker who was killed in northern Alberta last June.

The most recent Report on Workplace Fatalities and Injuries found that 590 workers in Canada died from occupation-related diseases, and 335 died from workplace injuries in 2019.

Besides the loss of life and environmental damage, these incidents are expensive; the associated production losses, absenteeism, medical costs and workers’ compensation payouts equate to four to five per cent of the annual global gross domestic product (GDP).

Learning from past mistakes

As researchers with an interest in workplace safety, we wanted to understand: How do companies learn from their mistakes? What motivates them, and their industries, to change their ways? Monetary penalties? Deeper reflection from analyzing the causes of the infraction? Public scrutiny?

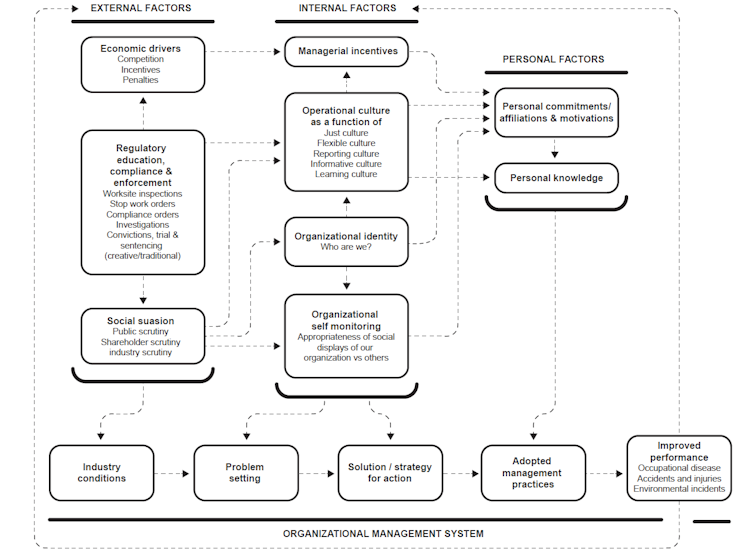

To answer these questions, we (an engineering professor, an economics professor and a business professor) developed a testable model of how different types of regulations affect companies’ safety performance. We examined the injury rates of 87 Albertan employers found guilty and sentenced for environmental and occupational, health and safety infractions from 2005 to 2018.

Our work is among the earliest to quantitatively examine the effect of incidents and sentencing type on companies’ safety performance, for two reasons. First, is a lack of data access, which we overcame by connecting with several forward-looking government ministries: Alberta Justice and Solicitor General, Alberta Environment and Parks, Alberta Labour and Immigration.

Second, our approach is interdisciplinary, meaning it combines research from several fields. There are a few assumptions each field tends to make: economists expect companies to maximize expected profit, management researchers expect companies to avoid incidents that create public scrutiny and engineers expect companies to adopt the best technical solutions.

Individually, all these perspectives have blind spots. For example, economists might fail to see the hidden costs associated with incidents, such as reputational impact, or management researchers might overlook how incidents are under-reported and unevenly covered by media. Together, our research is able to overcome these shortcomings.

Fines are not (always) the way to go

Our results suggest that creative sentencing provided more effective and longer lasting deterrence for offending companies. Instead of paying fines, creative sentencing uses funds to promote better workplace safety, like better industry training.

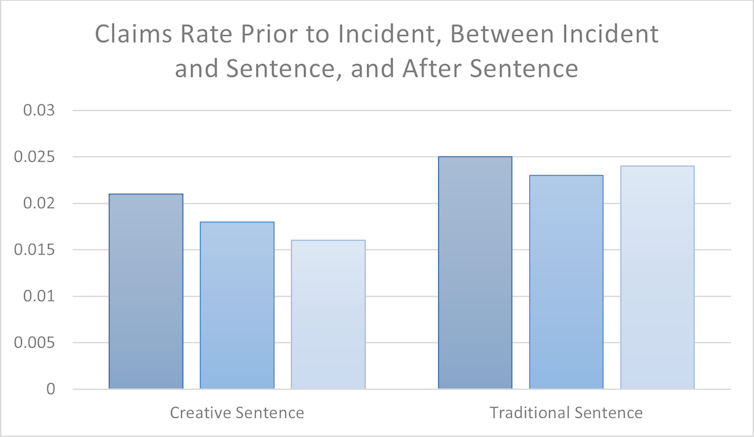

When a serious incident happened, we found a small reduction in a company’s injury rate, even before they were sentenced. This suggests that incidents motivate companies to change their practices prior to prosecution and sentencing.

With traditional sentencing, like fines or imprisonment, companies’ injury rates rebounded within two years. With a creative sentence, companies’ injury rates remain lower for at least two years. In other words, our research suggests that creative sentencing and case-study learning improves performance, while economic fines do not.

A possible explanation for this is that major incidents focus managerial attention on improving company practices, while creative sentences reinforce these improvements.

Why isn’t creative sentencing used more often?

This begs the question: If creative sentencing improves company behaviour, why don’t more jurisdictions use it? The answer is that fines are easy — justice departments collect money from offending companies and it goes into government general revenues. Fines are simpler for companies too — they just need to write a cheque.

In comparison, creative sentencing requires much more work. There needs to be a detailed examination of the incident’s root causes, agreement on the right creative fixes to put in place and appropriate follow-through to hold the company accountable for those changes.

The root causes, and subsequent fixes, are often complicated. Workers feel rushed and take shortcuts, or they might be contractors who don’t have access to their company’s work procedures. Perhaps work procedures are overly detailed, complicated and difficult to follow. Or only one specific person knows and they’re home sick that day.

A justice department has to monitor a company (sometimes for years) while it unravels the causes and enacts fixes, then check the company’s homework.

Our firsthand experience working with companies and creative sentencing is that this is time-consuming, technically and organizationally complicated and emotionally exhausting. Company operations are messier than our model portrays.

This work is incredibly important to do, despite how tedious and difficult it can be. Only by examining these complexities, and enacting creative solutions, can we learn from incidents and fix the causes. While a workplace fatality is a tragedy, an even greater tragedy is not learning from it.

Lianne M Lefsrud receives data from the Government of Alberta Workers' Compensation Board and funding from the Social Science and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) of Canada, Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada, Alberta Justice and Alberta Occupational Health and Safety.

heckert@ualberta.ca receives funding from The Government of Alberta, Ministry of Labour and Immigration.

Joel Gehman is a co-investigator with Lianne M Lefsrud on grants related to this research program.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.