The homes that the extended family of Chaudhary Devi Lal has built resemble mini forts. Against the neighbouring amalgam of modest brick-and-mortar homes and shops, the stone structures featuring battlements, arches, and carved wooden doors appear medieval in Sirsa’s Chautala village on the Haryana-Rajasthan border.

If homes are anything to go by, theirs say a lot: of the political power they yield locally of course, but also of their heritage as part of the wealthy, landed Jat community. Mostly though, they speak of lineage derived from Devi Lal — freedom fighter, farmer activist, and founder of the Indian National Lok Dal (INLD). A local leader who rose to national prominence, he was the sixth Deputy Prime Minister of India (1989-1990).

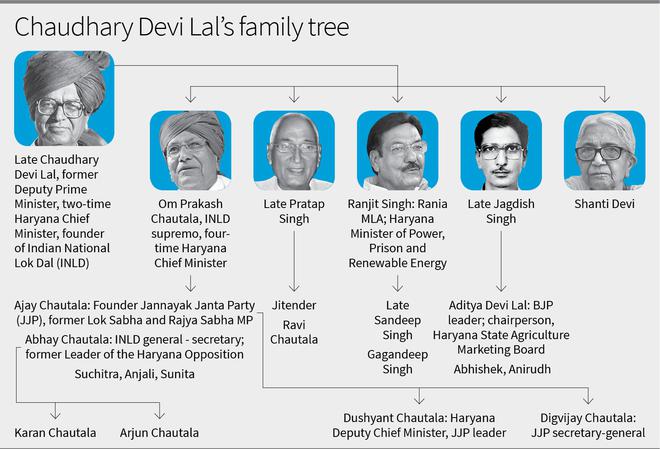

When Devi Lal died in 2001, having lived his 87 years across India’s many growing stages, his mantle was taken on by his son, Om Prakash Chautala, the oldest of five siblings. In time, power has been shared with 10 or more people in the clan, as the original INLD broke up and children and grandchildren began to assert their own personalities, each claiming to be the torchbearer of the patriarch. Today, as the Chautalas feud, the Congress and the BJP are hoping to make inroads into the family fiefdom that spreads across six of Haryana’s 22 districts.

An indication of the clan’s decline in power is shown through results of elections to the 90-member Assembly. In the 2009 poll, the INLD had finished with 31 seats and its vote share was 25%, just behind the Congress’s 41. In 2014, the BJP won a simple majority riding the ‘Modi wave’ in Haryana; the INLD dropped to 19 seats with the vote percentage intact, finishing ahead of the Congress, which won only 15 seats. In 2019, the INLD secured just one seat.

A family splintered

Today, at the heart of the battle is the rivalry between two of Om Prakash Chautala’s descendants: Abhay, his younger son, and Dushyant Singh Chautala, the current Haryana Deputy Chief Minister, and his grandson from his older son Ajay. The family feud began in 2018, when the original INLD splintered, with Dushyant, his father, and mother, Naina, an MLA, carving out the Jannayak Janta Party (JJP); a sobriquet for Devi Lal, ‘Jannayak’ means leader of the people.

In the 2019 Assembly election, Dushyant won Uchana Kalan, a stronghold of the Chautalas, from where his grandfather, Om Prakash, had once stood and won.

His party secured 10 seats and entered into an alliance with the BJP, which was six short of the majority mark of 46, but it angered a section of his core support base, the Jats, who had voted for him against the BJP.

The farmers’ agitation against the agriculture laws of the BJP-led Centre that began in 2020 and lasted for over a year, further eroded Dushyant’s support base. It tilted the scales in favour of the politically marginalised INLD. Most people in Haryana have some connection with farming, and many party workers, who had earlier shifted their loyalties to the JJP, are rethinking this.

A slogan on the parapet wall of a water channel running through Uchana Kalan Assembly constituency’s Karsindhu village says, “Abki baar Abhay sarkar (This time, Abhay government)”, signalling how a section of supporters of the Chautalas, disappointed with Dushyant, is now realigning with the INLD.

“I have always voted for the Chautalas, but not this time,” says Ishwar Sharma, 60, sitting on a wooden chair beside a group of men puffing at smoke cones and playing cards in the late afternoon, a common practice in rural Haryana.

Kapoor Khatkar, another villager, adds that Dushyant had not kept his promise of providing irrigation facilities and drinking water to the village. All this is seen against the Devi Lal legacy of introducing the pension scheme and abolishing commercial vehicle tax on tractors.

Both the INLD and the JJP use images of Devi Lal on their flags and hoardings at rallies, claiming to be his true heirs. The leaders of both factions talk about Devi Lal, his vision, and the model of politics in their speeches to present themselves as ‘real’ inheritors of his legacy.

Personal and political

Buoyed by the declining popularity of the JJP, Abhay has embarked on a 215-day padayatra (journey on foot). Flagged off by Om Prakash in Nuh’s Shringar village on February 24, it will pass through all Assembly constituencies in the State. Led by Abhay and his sons Karan and Arjun — with intermittent appearances by Om Prakash — the yatra targeting the party’s core vote bank, mostly the Jats, will traverse almost half of the State’s 6,000 villages.

INLD spokesperson Rakesh Sihag says the 2024 Assembly election is significant for the party. “We are not only targeting the party’s core voters in villages but also holding public meetings in cities in order to expand to urban areas. Even if we manage to win back our core vote bank that was ceded to the JJP, it will be a big boost to the party’s prospects,” he says.

The split in the party has not just pitted the Chautalas against each other politically but also soured personal relationships. In a video that went viral after the split, Om Prakash’s wife Sneh Lata, before her death in 2019, gave instructions that her son Ajay’s family not be allowed to touch her body.

Dushyant has, on a couple of occasions, posted pictures on his social media accounts seeking the blessings of his grandfather, but Om Prakash and Abhay did not attend Dushyant’s younger brother Digvijay’s wedding earlier this year. In fact, Om Prakash will contest the next Assembly poll from Uchana Kalan, against Dushyant.

Abhay, in one of his speeches at ‘Parivartan Padayatra’ in Fatehabad recently, attacked the JJP, and said, “Now, people have come to understand that these impersonators carrying the picture of Chaudhary Devi Lal are standing at the front to plunder the State. The people are disappointed and want them out of power.”

Dynastic disintegration

In Chautala village, Pirthi, 60, remembers Tau, as Devi Lal was called fondly in these parts. He would visit the village every month even after he shifted base to Delhi, India’s power centre, walk around sans security, meet villagers and farmers, and listen to their grievances. “Bees saal ho gaye, lekin aaj bhi yaadein taazi hai. Unke jaisa neta na kabhi dekha, na dekhne ko milega (It has been 20 years, but the memories are still fresh. We have not seen a leader like him, nor will there ever be anyone like him),” he says.

Devi Lal was born to a family of landlords in Teja Khera village, Sirsa district, on September 25, 1914, but his parents relocated to Chautala village when he was five. He was elected as an MLA in 1952. His older brother, Sahib Ram, who became a Congress MLA from Hisar in 1938, was the first politician in the family. He had trained as a wrestler, was imprisoned as a young freedom fighter, and advocated for Haryana’s statehood.

Prakash Badal, sitting next to Pirthi on a cemented platform under a large-canopied tree in the village, says he was a teenager when Devi Lal gave the call for “Ek vote, ek note”, seeking both political and financial support during the elections after the Emergency in 1977. He became the Chief Minister of Haryana thereafter.

In fact, Dushyant’s “Ek booth, dus youth (one polling booth to 10 youth)” echoed his great grandfather’s initial message.

Reaffirming the relevance of Devi Lal even today, considering he is still fresh in voters’ memories, Union Home Minister Amit Shah remembered him at a rally in Sirsa four weeks ago. He said Prime Minister Narendra Modi was the only one to fulfil Devi Lal’s dreams for the farmers in the State. Whether they align with the INLD or the JJP, it is clear that the Chautalas remain at the core of the BJP’s electoral strategy in Haryana ahead of the 2024 Assembly poll.

“Expecting a direct contest with the Congress in Haryana, the BJP will need the Chautalas to cross the majority mark in the event of a hung Assembly. The Chautalas too will be more comfortable supporting the BJP over the Congress as history suggests,” says Rajendra Sharma, head of the Political Science Department at Maharshi Dayanand University, Rohtak.

New fronts

The second and fourth of Devi Lal’s four sons (the youngest is a daughter and not in politics) — Pratap Singh and Jagdish Singh — are no more. Pratap’s daughter-in-law, Sunaina Chautala, entered politics in 2018 and heads the INLD’s women cell.

Ranjit Singh, the third son, rebelled to join the Congress. He is now an Independent MLA from Rania and the Power and Energy Minister in the Haryana government.

Adding a new dimension to the legacy debate is Aditya Devi Lal, Jagdish’s son, who made his political debut defeating Abhay’s wife, Kanta, in the Zila Parishad elections in the Dabwali Assembly constituency in 2016.

At the original Devi Lal house in Chautala village, where Aditya and a few other family members live, he says he was forced to join the BJP after he realised that the Chautalas did not want him to grow politically. “I made every possible effort to unite the entire clan before the 2014 Assembly poll, but I decided to quit after I realised that they wanted to sideline me,” Aditya says.

He also feels the Chautalas are “busy amassing wealth” and “only use Tau’s pictures”. He says only he has revived Devi Lal’s name as it appears with his own name on foundation stones and inaugural plaques. “I live him every day,” says Aditya, surrounded by about 10 supporters.

He had unsuccessfully contested the Assembly election in 2019 from Dabwali on a BJP ticket, but was recently appointed the chairman of the Haryana State Agriculture Marketing Board, enhancing his political stature in the region.

The villagers of Chautala, however, seem divided on the question of legacy. Gagandeep, an ardent INLD supporter, says Abhay’s popularity is on the rise after he resigned as an MLA in protest against the farm laws and he will be the next Chief Minister. “He is a man of his word,” he says.

Surender, a Dushyant supporter, disagrees. “Dushyant resembles Chaudhary Devi Lal not just in his looks and manner of speaking but also in his friendliness, like Tau himself. He remembers workers’ names and mixes with them when he visits the village,” he says.

At the ancestral home, Rajendra, a BJP supporter, stressed the resemblance between the pictures of Aditya and a young Devi Lal hanging on a wall. “Though Aditya’s father Jagdish never joined politics, he too, like Chaudhary Devi Lal, was very popular in the area for being helpful. He would often offer villagers waiting for transport at the village bus stop a lift in his jeep,” he says.

Miyan Khatkar, 70, a resident of Karsindhu, feels no one has the kind of political or personal presence that Devi Lal had. “Had the Chautalas stayed together, they could have been strong challengers to the Congress and the BJP,” he says, his wisdom echoing through the village.