Chicago Public Schools is poised to make a significant change to the admissions process for its coveted test-in elementary and high schools in an attempt to award more seats to low-income students.

In one of his first major moves as CEO, Pedro Martinez is proposing that the school district drop part of the current system that awards 30% of the seats at these schools — including for the nearly 16,000 students at 11 selective enrollment high schools — strictly based on a student’s seventh grade marks and test scores. This would almost certainly open up more seats to a more diverse student population and make it more difficult for students from the city’s upper-income neighborhoods to get in.

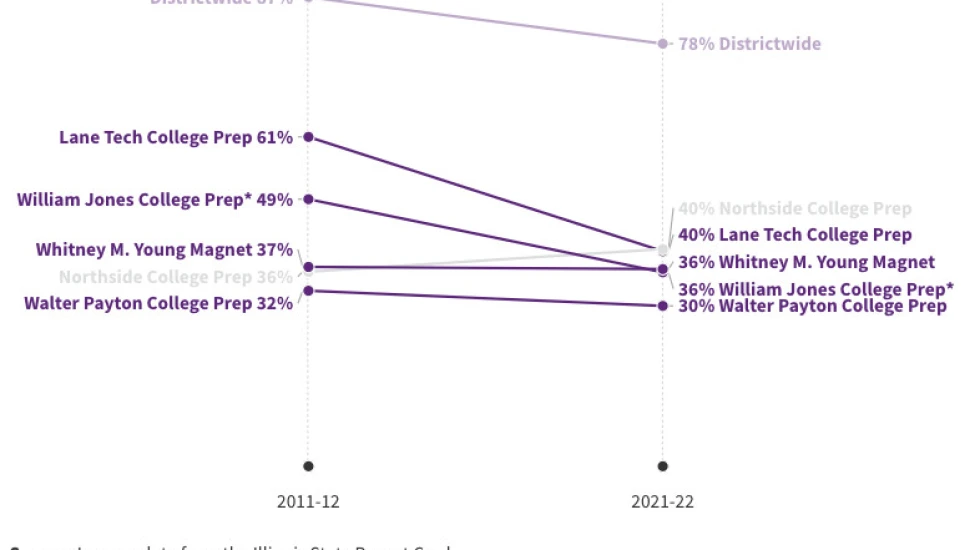

It is a move some have long advocated for, especially as the student population in some of the most coveted schools, including some of the top schools in the state, have become more affluent, white and Asian.

Most of the seats at these selective schools — 70% — are divided among four groups of students based on the socioeconomic characteristics of where they live. Students earn a score out of 900 based on their grades and test scores and then compete for seats against students in their same socioeconomic group.

Another 30% of the seats are awarded exclusively to students who earn the most points in the admissions system — and those seats mostly go to higher-income students. In the 28 selective enrollment elementary schools, 85% go to students in upper-income areas, and in high schools, it’s 73%, according to CPS.

Officials say they want to make the process more equitable. They are proposing either getting rid of the rank order set aside or reserving more spots for students for lower-income communities.

This would be the most significant change to the admission process since 2009, when CPS was forced by the courts to drop race as one factor in admission. Instead, it began weighing a student’s socioeconomic status, in large part as a proxy for race.

This new change would make the admissions process more fair, rather than having it tip in favor of students from middle- to upper middle-class communities, said Lauren Sartain, a professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and an an affiliated researcher at the University of Chicago Consortium on School Research.

“It means that a student living in a low-income neighborhood who has a high academic record, high test scores and high grades is equally as likely to get into a selective enrollment high school as a student who is from a higher-income neighborhood also with high test scores,” she said.

CEO Pedro Martinez says this is important to him.

“I believe academic ability is distributed equally across our city and that access to our selective enrollment schools should be more equitable,” said Martinez, explaining the proposed change in a video.

The change wouldn’t take effect until the application process next year for students applying for fall 2023. The school district is surveying parents about the change and is holding an information session Thursday evening.

CPS officials have long maintained a desire to ensure the selective enrollment schools, which were created as a result of a 1980 federal desegregation consent decree that was lifted in 2009, are diverse.

Nate Pietrini, who runs High Jump, a program to help low-income students get into top high schools, said doing away with the rank order is a change many people have long wanted.

“It’s something that I and a number of folks have been advocating for years,” he said. An analysis by a group that Pietrini works with indicated that about 500 more low-income students could earn a seat in a selective enrollment high school without the rank order, he said.

Still, the bigger problem is that not all schools offer high-quality programs, he said.

Pietrini spent five years as principal of Hawthorne Elementary School in Lake View on the North Side, an area with many affluent families. He said it might be difficult for some parents to understand this policy change since it can be challenging for students from upper-income areas to get into top schools now.

Last year, students in the highest income areas had to get nearly a perfect score to get into Payton College Prep and Northside College Prep and a high score to get into Lane Tech, the three closest selective enrollment high schools.

“People generally are for increasing access and increasing equity, until it becomes about their own situation or what you perceive to be best for your own kid, and so I would have to do a delicate dance,” Pietrini said.

Arjuna Ariathurai, chair of the Hawthorne Local School Council, said he expects the complaints will come after the change when students with perfect scores end up getting rejected from their top choices. Ariathurai said there’s already an assumption that a higher income student with a B average or one who scores in the 85th percentile on standardized test scores must look at other options.

But Ariathurai wonders if this change will really solve the problem of limited enrollment of low-income students at some of the most coveted selective high schools, some of which are far from their homes.

He also wonders how students who are not as qualified might fare in the highly competitive selective high schools.

Some research shows that selective enrollment schools are not always the best choice for students, Sartain said. High-performing students tend to do well regardless of where they go, she noted. And there’s some evidence that high-performing students from low-income backgrounds from neighborhood high schools get into more selective colleges than those that go to selective enrollment high schools.

“Families should think about all the options that they have available to them and think about their children, and what would be the best fit both academically and also socially,” she said.

Ursula Taylor, who is on the Local School Council at Lincoln Elementary School in Lincoln Park, said she hopes this policy change gets people in her affluent community talking about how they can exit the “rat race” that accompanies trying to get into a selective enrollment high school. She said the parents in the neighborhood should be able to support a local school where they can feel comfortable having their children attending.

Lincoln Park High School, which has both neighborhood and selective programs, has become more of an option for local families, she said. But there’s still a heavy emphasis on the elite selective enrollment high schools.

“The seventh graders are carrying a burden on their shoulders,” Taylor said. “They’re stressing about every grade, the test scores. It’s like they’re in high school applying for colleges, but almost worse.

“I don’t think we need to do that in Lincoln Park,” Taylor said. “We shouldn’t need to do that anywhere. But there’s really no excuse for it here. Why are we in this fear-based mentality? Why do we have a scarcity mentality about our children’s education in Lincoln Park?”

Sarah Karp covers education for WBEZ. Follow her on Twitter @WBEZeducation and @sskedreporter.