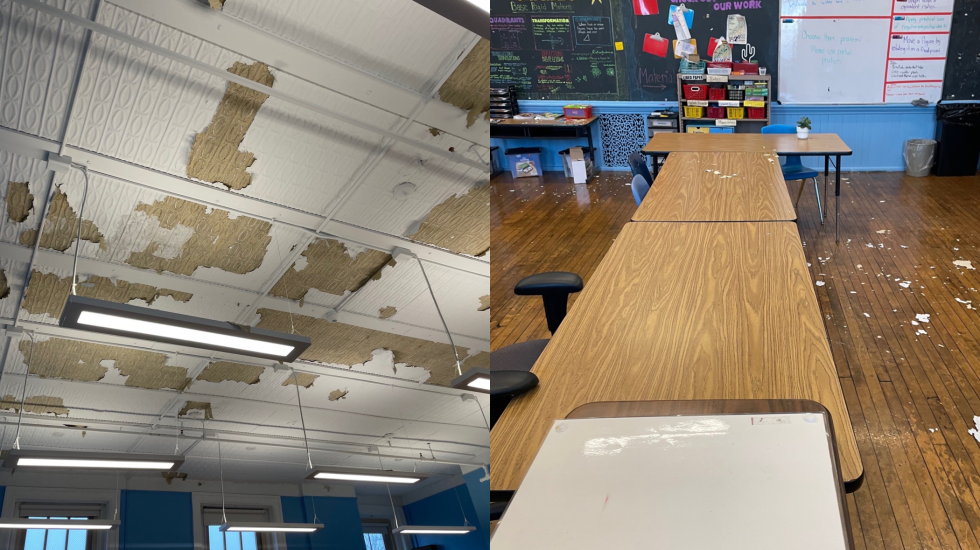

Teachers and other staff members at McClellan Elementary School in Bridgeport complained for months last fall about peeling lead paint and the hazard it posed for students.

Finally, after months of pushing for action and news coverage and after teachers tested the paint on their own and found lead, Chicago Public Schools officials had the dangerous paint removed over winter break.

“We asked many times,” said Kelly Harmon, a special education teacher at McClellan whose room had flaking paint chips. “Our administration kept emailing [CPS officials], and they kept hearing back that it wasn’t a problem.”

But records obtained by WBEZ show CPS officials knew the paint was a problem. In August 2021, they found deteriorating paint in Harmon’s room and the school gym, records show.

And yet students remained in Harmon’s classroom — where deteriorated lead paint was found on the ceiling and one wall — until CPS made repairs the following June, 10 months later.

The paint in the gym also was taken care of in June 2022 — nearly a year after it was identified.

But additional tests that month uncovered even more damaged lead paint in Harmon’s classroom and a nearby room.

According to CPS, the paint finally was removed in both rooms six months later, over winter break.

Inspectors recommended that CPS “notify all facility users” of any positive test results, but teachers said they were kept in the dark.

CPS officials would not say why they kept Harmon and her students in a classroom with chipped lead paint for nearly a year.

Of the additional six-month delay in removing the paint identified in June 2022, CPS blamed a breakdown in communication.

Last fall, Cindy Goga was among McClellan parents who spoke out about the problems. Goga, whose two kids attend the school, said the city failed her children.

“Every morning, parents come to this school, and we drop our students off thinking that they’re going to be safe and well taken care of,” Goga told reporters then. “Imagine our dismay when we found out that the building itself was dangerous.”

CPS knows that many of its older buildings have lead paint. And it routinely tests for lead paint deterioration ahead of construction work.

Intact lead paint isn’t hazardous until it peels or flakes, but CPS officials said it should be fixed and the areas where it’s found should be blocked off while it’s safely removed.

This past school year, workers found lead-based paint at 95 elementary schools and 24 high schools, according to CPS. Almost every one of those schools had deteriorating paint in some rooms and required remediation, according to a WBEZ analysis of records between June and January.

In a written statement, CPS officials said they work to respond “quickly and efficiently to any and all environmental issues and potential risks.” They said they put a new system in place after the situation at McClellan last winter to help ensure there’s better communication and a speedier response.

They said average time between testing and mitigation is about 10 working days and that the actual time depends on factors including the extent of damage, its location, the availability of additional space and the school’s schedule.

CPS also said every deteriorating lead paint project that required removal this past school year at the 119 affected schools, including McClellan, was completed and that “the facilities were returned to use after completion.”

But CPS records show 11 ongoing projects won’t be completed until this summer and five more don’t appear to have been scheduled yet.

When WBEZ spot-checked schools where CPS said mitigation work was done, school staff members said it was incomplete or documented incorrectly, raising questions about the accuracy of CPS’ records.

At McClellan, after Harmon and others demanded action, workers tested across the campus over winter break and made repairs in time for school to resume in January.

Inspectors found more chipping lead paint in parts of at least nine rooms as well as the staff lounge, the main office, the assistant principal’s office, a stairwell landing and other areas. The principal said CPS pledged to prioritize mechanical improvements in the humid school to prevent paint from cracking and peeling.

McClellan runs a program for students with significant disabilities, including some who are medically fragile. Harmon said many of the students in rooms found to be contaminated by lead have sensory needs, making them more likely to put their hands in their mouths.

Banned but still on school walls

Lead-based paints have been banned in facilities like schools and for residential use since 1978, but many CPS schools predate the 1970s and contain lead paint that could require mitigation.

CPS officials note that its mere presence does not present a hazard if the paint is in good condition. They said minor paint damage, including scratches and small chips, are “not uncommon and do not pose an exposure risk” and that these areas are “monitored and touched” up to prevent further damage.

But the paint poses a hazard if it’s chipping, especially if there’s dust. The area is supposed to be isolated, cleared up and mitigated.

No amount of lead exposure is considered safe for kids.

“It’s dangerous because, when it deteriorates or pulverizes into dust, children inhale it or ingest it — usually by putting their hands in their mouths,” said Dr. Susan Buchanan, a clinical associate professor of environmental and occupational health sciences at the UIC School of Public Health who is director of the Great Lakes Center for Reproductive and Children’s Environmental Health.

Buchanan said paint dust remains the top source of lead poisoning in children. Kids also can be exposed if they chew on surfaces coated with lead paint, including window sills and door edges, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“For children, it directly interferes with neurodevelopment,” Buchanan said. “We have very good evidence of loss of IQ points and behavior problems from lead poisoning.”

Illinois law requires that all children 6 or younger be evaluated for lead exposure and tested if necessary to enroll in daycare, preschool and kindergarten. Buchanan recommends annual blood tests starting from nine months to 6 years old.

She said there are no guidelines recommending blood screening for teenagers because they don’t have the same exposure risks as younger children. “They’re not sucking on toys … so they shouldn’t have that same level of exposure,” Buchanan said.

But Harmon said even older kids sometimes put their hands and toys in their mouths due to a disability or sensory needs.

“Any lead is too much lead, regardless of age or disability,” she said.

Some schools have ongoing problems

In December, workers found deteriorated lead paint in Room 207 at Libby Elementary School in Back of the Yards, CPS records show. Six months later, CPS confirmed it has not scheduled any remediation work in the classroom, saying repairs to the roof must be completed before the classroom ceiling can be fixed.

Kids were present in the room throughout the school day, and the area hadn’t been blocked off.

“When you lift up the ceiling tiles in our building, you can see the original” lead paint, said Jonathan Eigenbrode, a Libby teacher who is a Chicago Teachers Union delegate. “And then, on the third floor, there’s a lot of paint that is literally flaking, chipping or water damage off the walls.”

CPS removed lead paint from the main entrance, kitchen, lunchroom and other areas at Libby over winter break but “never finished the job,” according to Eigenbrode, not painting over the areas that were mitigated. According to CPS, a lead mitigation job is completed only when the area is coated with a surface primer.

“You can see where CPS had come in and patched up areas,” Eigenbrode said. “How are [students] supposed to enjoy going to school if it constantly looks the way it currently looks?”

Eigenbrode said he hopes Mayor Brandon Johnson’s administration will offer “more feedback and less runaround.”

“I’m optimistic because I’ve seen a lot of changes happen very quickly when I start pointing things out,” he said.

Schools are responsible for communicating with kids families and with staff members before the start of any environmental mitigation work and after the work is complete, according to CPS.

Officials said they test and mitigate damaged lead paint when buildings are unoccupied, including during breaks and after school hours, allowing workers to scrape off any lead paint and cover the area with primer and new paint.

“My No. 1 job here is to ensure that our students are safe … so anytime [lead issues are] brought to my attention, I want to get ahead of it right away,” said Charlene Reynolds, the principal at Dewey Elementary School in Fuller Park on the South Side.

In February, workers found chipping lead paint in the third-floor gym at Fuller. Students would knock ceiling tiles loose with balls, exposing the paint underneath.

Reynolds acknowledged that the area was never blocked off from students and has remained in use.

CPS officials said the damaged lead paint in the gym will be repaired before students return in the fall.

Reynolds said she’s not aware of any children who became sick as a result of the lead paint.

According to experts, though, lead poisoning can be hard to detect. Even people who seem healthy can have high blood levels of lead, according to the Mayo Clinic, affecting a child’s mental and physical development.

“Of course, it would be nice to know that you’re walking in to a building that does not contain any lead,” Reynolds said. “But, because I have not had any complaints from students or their parents, I haven’t been uber concerned about it.”

Workers also found deteriorating lead paint in two classrooms, a few bathrooms, the boiler room and other areas during a construction project last summer. It was fixed before the start of the school year, CPS records show.

Reynolds said the lead paint was beneath a layer of latex paint throughout the building.

“Kids would pull it off,” she said. “It was something that they just liked to do. It was a concern because I knew how old the building was, that possibly there was some lead.”

After CPS fixed that deteriorating paint, Reynolds said the entire school received a new coat of paint during summer break — blue and gold, the school’s colors.

CTU asks teachers to report problems

The CTU created a Google form for members to report potential hazards like deteriorating lead paint and asbestos. Fifteen teachers flagged environmental issues this past school year, according to Lauren Bianchi, a teacher at Washington High School who chairs the union’s climate justice committee.

“We’re encouraging people to make sure you are including the union in that conversation so we can make sure that there’s follow-up and that we can document just how many schools are having these issues,” Bianchi said.

After the lead issues at McClellan Elementary became widely known in December, CPS officials said they said it implemented a new system to address environmental complaints in a more timely manner. They said they’re also expanding training for all building managers, engineers and custodians to help identify potential paint-related hazards.

Bianchi said the union has distributed store-bought lead tests and done campus walk-throughs to help teachers document environmental hazards. She said it typically takes an emergency — and community uproar — for CPS to address lead issues quickly.

“There needs to be a systemic remediation and greening of all of our schools, starting with schools like mine in environmental justice communities,” Bianchi said. “Black and brown communities that are most divested in should be first in line.”