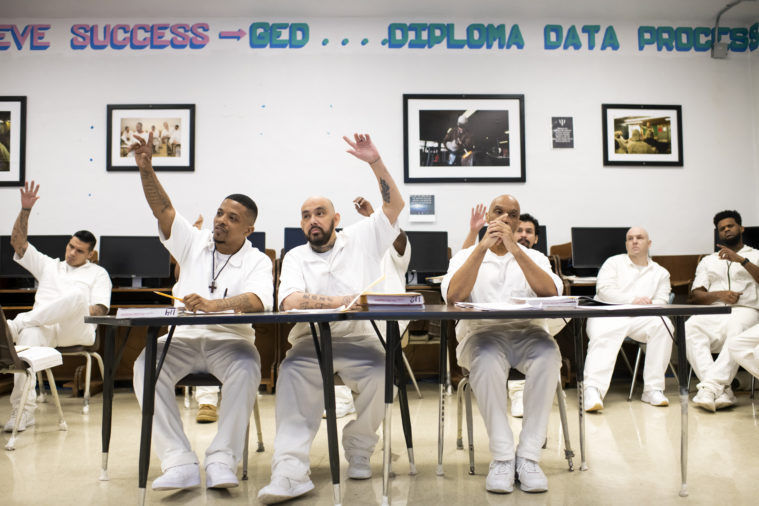

On a lower level of the Wynne Unit, a state prison in Huntsville, about 20 men in white jumpsuits and matching white sneakers sit around the perimeter of a room. Their attention is focused on Paul Allen, who stands in front of them. He’s a familiar face in the unit of about 3,000 male prisoners: He’s been teaching there for years. Today, he’s leading the men through their capstone business course, for many the final step on the path to getting their associate of applied science degrees in business.

“We’ve got some geeks in here,” said Sherman Griffin with a laugh from his place in the back row. “And they’re smart. And it’s OK to be smart.” These men are learning entrepreneurship and creating their own business plans. One hopes to open a bar and grill, another a technology company.

Elkanah Hendrix, 40, sits in the front row. He has decades of martial arts training and wants to start his own virtual training school. “I have three children, and they won’t allow me to see this as incarceration,” Hendrix said. “They say, ‘Daddy, you’re away at college.’”

Many of them probably wouldn’t be in college if they hadn’t gone to prison. Only about 40 percent graduated from high school. The classes at the Wynne Unit—run by Lee College, a Baytown-based community college—are among the most diverse course offerings in the Texas Department of Criminal Justice (TDCJ), ranging from accounting to horticulture to welding. But something else also sets these men apart: They can get federal money to pay for their education, an advantage long withheld from the vast majority of other incarcerated people.

For decades, nearly all prisoners have been excluded from applying for Pell Grants, one of the biggest sources of federal need-based funding for U.S. college students. This policy, which was the result of the tough-on-crime era of the late 20th century, decimated prison education programs nationwide.

Thanks to an order by the Biden White House, the funding will become available next July to people inside.

Nearly 70 institutions across the country, including the one in Huntsville, got an early infusion of funding from the program via the Obama-era Second Chance Pell program. Today, seven colleges operate Second Chance Pell sites in Texas. Altogether, they serve 3,338 students, according to a count from the Vera Institute, which monitors the program.

These units, some of which have benefited from Pell funding for more than five years now, provide a unique look into what the return of Pell might mean for people in prisons, especially in Texas, which has one of the nation’s highest incarceration rates.

“With Pell assistance, they’re able to continue their education and really begin to think about what type of life they want to have following their incarceration,” said Allen, the academic division chair of the Wynne Unit program.

Donna Zuniga, now associate vice president of the Lee College Huntsville Center, has worked with the college for 35 years. She saw the difference before and after nationwide Pell funding went away.

In 1993, the year before Pell was ended for prisoners, 239 people in Texas earned their associate degrees and 41 earned bachelor’s while serving their sentences. By comparison, in 2015, only eight received their bachelor’s while incarcerated. By 2021, the number had ticked up to 17 but still remained a fraction of the graduation rate before the funding stream was cut off.

Zuniga has also seen other programs drop off, including the federal youthful offender grant, which helped cover tuition and fees for people in their teens and early 20s. At one point during her tenure, 78 percent of the college’s prison education budget had been stripped. But she’s always been determined to keep operating—she knows prison education programs have been proven to reduce recidivism and make individual units safer, among other benefits. Lee College has tracked the status of its students who were released in 2018: Their recidivism rate was 6 percent, compared with just over 20 percent for prisoners statewide.

“I have three children, and they won’t allow me to see this as incarceration. They say, ‘Daddy, you’re away at college.’”

She and her team have scrounged for grant money and convinced businesses to donate to the technical programs to offset tuition costs for students. TDCJ also received funding through the state Legislature for education programs, albeit far less than that body originally offered in the 1990s. “And then, of course, Second Chance Pell in 2015 was a game changer,” Zuniga said. She estimates that right now, at least 85 percent of Lee College’s incarcerated students—who number around 1,200 each semester—receive some amount of Pell funding.

In Texas, the restoration of Pell Grant funding systemwide next year will give the state prison system a unique opportunity to reduce the yawning chasm in educational opportunity between units.

Twelve community colleges and two universities currently run higher education programs in 33 Texas state prisons—the other 69 state lockups (including privately-operated units) have no programs at all. Half of the educational institutions also participated before Pell ended in 1994, according to data from TDCJ.

Some courses are restricted to inmates nearing the end of their sentences. Although courses can be limited to one per semester, many prisoners accumulate credit toward degrees and earn certificates in fields like construction, culinary arts, and automotive tech.

In Texas, men get far more educational opportunities in prison than women.

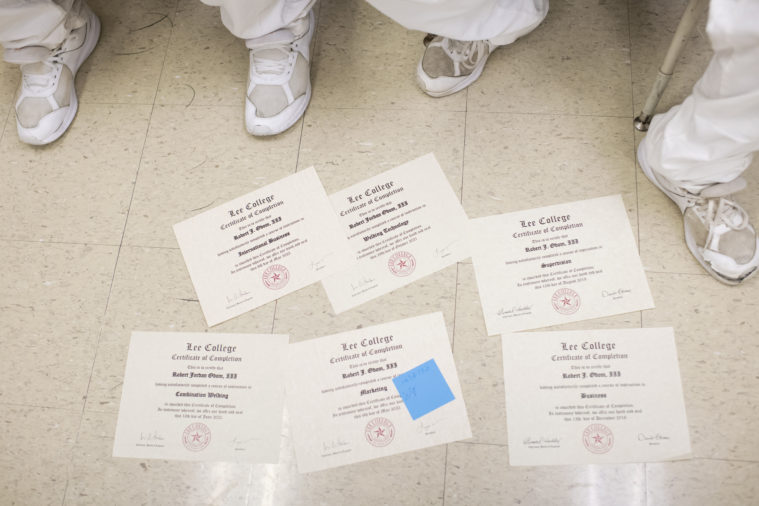

“When you give us education, and we come in here and we accomplish something, we’re learning,” said Robert Odom, another student in the business class. “We’re learning that we can go out into the world and we can become somebody. So you’re not just investing in our education; you’re investing in your own community.”

Modern prison education programs began to take shape in the U.S. in the mid-20th century. At that time, participants could get funding for their education from a deep well of federal sources: the Office of Economic Opportunity, the Veterans Administration, the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration, and the GI Bill. Then, in 1972, when Pell Grants—originally called the Basic Educational Opportunity Grant Program—were created, incarcerated students could apply for funding based on income.

For the next two decades, Pell was the single biggest source of funding for higher education programs in prison. Where the money flowed, the opportunities followed. Then conservative commentators took up Pell funding for prisoners as their cause du jour. Opponents claimed that prisoners were draining Pell coffers, leaving little for students on the outside. But this was a baseless argument: Incarcerated students made up less than 1 percent of the total Pell Grants awarded in 1993-94. Some even bizarrely claimed that providing this funding to prisoners would somehow incentivize crime, as if people would purposefully get themselves locked up in exchange for a “free” education.

Restrictions began under President George H.W. Bush, who signed a law making people sentenced to death or to life without parole ineligible. State prison systems were also put under the microscope to make sure financial aid was being used only for educational purposes. As political opposition to funding prison education grew within both parties, and the issue became part of the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, a sweeping piece of legislation that set the tone for years of harmful “tough-on-crime” rhetoric and legislation. The exclusion of prisoners from the Pell program had strong support in Texas, including from U.S. Senator Kay Bailey Hutchison.

By the 1995-96 school year, prisoner enrollment in higher education programs was halved, according to the Journal of Student Financial Aid. With funding greatly reduced, many programs downsized or closed.

For more than two decades, many people served time in prison with no access to higher education. Even if they could afford classes on their own—either through family contributions or by tacking on costs to parole fees—the lack of federal funding had discouraged colleges and universities from offering courses. Once-flourishing programs dwindled, with offerings at fewer facilities.

In 2015, the Department of Education under President Barack Obama launched its Second Chance Pell program. It opened the faucet to let the funding stream begin to flow—or rather, drip—once again to some incarcerated students.

Since then, these second-chance sites have become cities on the hill for those hoping to get a degree or certificate in prison in Texas.

But not everyone gets access.

Alexa Garza lives in Mesquite, a suburb of Dallas near where she was born and raised. Since her release, Garza has emerged as one of the most vocal Texas advocates for incarcerated women, whom she says are often a correctional afterthought. Nowhere is this more evident than in prison education programs.

Just a few days shy of her 20th birthday in 1999, Garza entered prison. She said she felt like her life was over, but there was a silver lining: She had been assigned to the Mountain View Unit, a state prison in Gatesville then known for its robust college program.

“I wanted to take advantage of everything they offered. Heck, I would’ve learned to drive a forklift. Would I ever drive a forklift? Probably not. But if they were teaching it, I was going to learn it,” Garza said.

The classes were run by Central Texas College and Tarleton State. Each session had a huge turnout, and to Garza it felt like a true college campus. But over the years, course offerings dwindled. If her classes were held at another nearby facility, the women had to be bused—a process that included multiple rounds of strip searches and a ride in a hot, cramped van. Despite the obstacles, she earned her Braille certification from the Library of Congress and a bachelor’s degree from Tarleton State University.

Garza is now planning for her wedding in November—she met her fiance soon after being released. But she discovered the hard way that not all of the skills she learned in prison could be easily applied: She had to work at a steakhouse because the parole board wouldn’t accept her contract work as a Braille translator as a valid job. She had to have a pay stub every two weeks on top of her translating work.

One of Garza’s best friends in prison has remained by her side after release. Jennifer Toon was incarcerated as a teen and was able to pay for her classes with the now-defunct youthful offenders grant.

“I wanted to take advantage of everything they offered. … If they were teaching it, I was going to learn it.”

Toon loved the early classes she took within TDCJ. She loved them so much she started crying in the dining room when she realized that grant funding would help her take more than one class per semester. But the gradual elimination of various funding streams eroded the educational offerings. “College is very different and it was whittling down. Now it’s not this privilege that feels like the college campus. Now it’s a punishment,” Toon said.

Toon paid an unusually high price for her education. While incarcerated, she was transferred to a different unit for a month to take a class. But the unit she was transferred to lacked air conditioning, and the degree program she was pursuing was set to end, which meant the credit from her class was useless. By the time she returned to Mountain View at the end of the course, it looked like Toon had lost 15 pounds in just one month, Garza recalled. Toon had basically stopped eating while at the other unit—the walk to the chow hall in the dead heat was too much.

The heat is a factor for other friends still in prison, Toon said.

“Now, as I’m reading the list of programs to a friend that we have at the Hobby Unit, asking, ‘Have you heard of this? Are you interested in college?’

“She said, ‘Girl, right now, I am so hot, I can’t think. I am trying to survive. I don’t care about those programs. Not right now I don’t.’”

Toon added, “When you’re wanting people to participate in educational programs, higher education or otherwise, if the conditions are not conducive to learning, you’re not going to get that participation.”

Culture change can be slow, even with the impending reinstatement of Pell funding. According to the Vera Institute, 85 percent of students enrolled in Second Chance Pell funding programs are men.

Toon has spoken with women who are still incarcerated and asked if they know Pell is being reinstated. Many had never even heard of the funding opportunity.

Back in Huntsville’s Wynne Unit, a group of male students meets for their truck driving course. It’s a massively popular class—the course often gets hundreds of applicants from units throughout the state vying for about 36 spots. When asked how many are paying for the class using Pell funds, which are need-based and don’t need to be repaid, more than half raise their hands.

Lee College has issued one of the highest numbers of Pell grants among the 67 initial second-chance sites around the U.S. The secret: Lee College counselors try to ensure every student who’s eligible gets enrolled in Pell. These counselors—Felix Buxkemper, Lance Byrd, and Tommy Crane—are semi-famous figures around the halls of the Wynne Unit. Men they’ve helped shout greetings as they walk by.

Bruce Corbell and Melvin Coleman teach the truck driving course. The Wynne Unit is in a perfect position to host it since TDCJ’s freight transportation division is based in Huntsville. Truck driving also tends to be friendlier than other trades to applicants with felony records. The class lasts for six months—five days a week, six hours a day. There are strict admission requirements: Students must have a clean disciplinary record for six months, a valid driver’s license, and no blemishes on their driving record.

Corbell, whose massive cowboy hat and white mustache would make him seem right at home on any of Texas’ sprawling ranches, recently heard from a former student. Thomas Lawless used a Pell grant to take the course at Wynne in 2017 and was released in 2019. Now, with the help of his commercial driver’s license, he works for Goodwill Industries. He recently took over as instructor for the company’s own truck driving course. He traveled to Huntsville this year to speak to current students about his outside success.

Tim Jones, deputy director of volunteer services operations for TDCJ, said prison college and certification programs—like the truck driving course—emerge in one of two ways: Either the prison system approaches the college or vice versa. On the agency’s side, they’re looking for vocational and technical programs that will help people get jobs immediately after their release—and for success stories like Lawless’.

“We’re looking for something that will give them a job skill,” Jones said. “When they leave, they can go right into it.”

About five minutes from the prison, an unassuming row of businesses is home to the administrative offices of Lee College’s Huntsville operation. There, in an office with posters on the wall that commemorate the college’s more than 50 years in correctional education, a trio works to help current prisoners and formerly incarcerated people make the most of their education.

Brandon Warren, Tracy Williams, and Matt McGinnis make up the reentry services department. Warren and Williams were formerly incarcerated themselves, and both earned degrees and certifications while serving their sentences. McGinnis is a former parole officer. They connect people with job openings, host support groups, and offer a six-week reentry class. They’ve got a mentor network and weekly Zoom calls where people can pop in with questions about how to navigate the job market with a leg monitor, or where to get the best outfits for job interviews.

These services, often called wraparound services, are the holy grail. Very few prison college programs offer such a holistic approach. But advocates hope that will change in the new Pell era.

The new funding stream will not kick on overnight. Colleges looking to set up shop or expand in prisons must go through a lengthy approval process, proving the programs they’ll offer will actually benefit incarcerated people. The stipulation comes from a very real problem in prisons nationwide: Many people are barred from working in certain industries or are denied jobs after release because of their criminal records, even though courses for these fields were offered in prisons.

Maggie Luna, policy analyst and community outreach coordinator at the Texas Center for Justice Equity, got her construction certificate while incarcerated in Texas. (The nonprofit seeks to end mass incarceration and make communities safer.) “When I got out, I was so excited that I had this certificate, only to realize that there was absolutely nothing I could do with it,” she said. “It was just a piece of paper. Nobody would hire me.” She said one man laughed when she showed him her certificate, saying she could have just gotten it online with no effort.

“That is heartbreaking,” Luna said. “I thought that was going to be my ticket out. … Access to education not only helps give people a purpose while they’re in there; it gives them a light to look forward to. And if these are meaningful programs that you can actually use in the world, it reduces the chances of recidivism.”

“I was so excited that I had this certificate, only to realize that there was absolutely nothing I could do with it. It was just a piece of paper. Nobody would hire me.”

TDCJ will be able to enter into and terminate contracts with colleges with some amount of discretion, so ostensibly the prison system itself will be charged with determining whether colleges are serving students’ best interests. TDCJ officials will also have access to more robust tracking data than before, which will help determine how well the program is working—and where it needs a tune-up.

One area of particular interest to advocates is accessibility for all incarcerated students. Certain programs and classes are only offered in certain units, so women and prisoners with disabilities or medical conditions can get left out of the system altogether.

“The first step in making sure that Pell is reaching its full impact is understanding that the men already have a foundation, but that the women, their foundation crumbled almost to dust,” Toon said. “They don’t have to reinvent the wheel over here with the men and Lee College and the other universities, but with the women, it’s like having a mansion over here and then you’ve got a dilapidated farmhouse. … And these are two different structures to build.”

The federal government is in the process of working out the details of how these funds are distributed and overseen.

Meanwhile, both formerly incarcerated people like Toon and veteran educators are hoping the benefits will be plain to see.

Zuniga, who runs the prison programming for Lee College-Huntsville, said she thinks “it will be easy for us to make the case” that restoring Pell will make a difference in the lives of incarcerated people, their families, and their communities.

“Everyone should have the right to an education,” Zuniga said.