In response to the cost of living crisis, the UK government has announced a number of measures – including a non-repayable rebate on energy bills for some households – to relieve the pressure from rising prices. While these are to be welcomed, they do nothing to tackle a much deeper social and livelihood crisis that has been building for decades.

Gaps in income have widened sharply since the 1970s. The share of national income taken by the top 1% has doubled, rising from 6% in 1977 to 13% in 2018. Because this rise has squeezed incomes among the rest of the population, especially those at the bottom, the level of child poverty (based on a relative measure) has also risen sharply, from 14% in 1977 to 27% in 2021.

The level of personal wealth, meanwhile, has been rising at twice the rate of incomes, while becoming increasingly concentrated at the top. Private wealth holdings now stand at nearly seven times the size of the UK economy compared with three times in the 1970s.

It hasn’t always been this way. In the late 1970s, Britain achieved peak equality and a low point for poverty. As shown in my recent book, The Richer, The Poorer, this was the high point of egalitarianism that drove transformative, progressive change after the second world war. Today’s crisis of living standards is due in large part to a steady weakening of post-war pro-equality reforms.

How peak equality was achieved

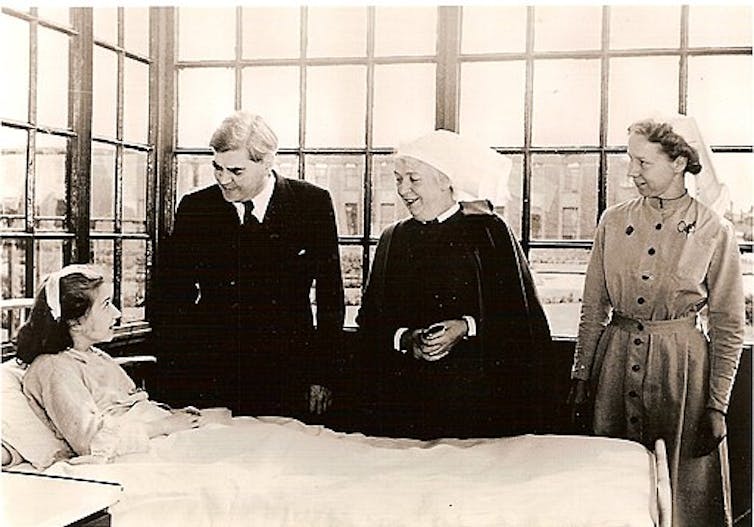

In 1945, the new Labour government, led by Clement Attlee, launched a wave of social reforms. Attlee, influenced by leading thinkers including the eminent historian and Christian socialist R.H. Tawney , saw his central goal as achieving “greater equality, fewer great differences, more opportunities, and more social justice”.

These reforms built a stronger welfare state. They included a more comprehensive national insurance system to cover unemployment, sickness and old age. Further, with the founding of the NHS in 1948, all were given direct access to free healthcare. And there was a new system of family allowances to support children, a measure extended by the introduction of child benefit in the late 1970s.

These reforms were paid for by a more progressive tax system which bore more heavily on those with the highest incomes. They were underpinned by a broad, if shallow, cross-party consensus on the need for social change. A new, informal pact was made with business to accept greater social responsibility. Full employment – unemployment was below 3% for men throughout the 1950s – and a rise in the share of output accruing to wages were both key factors in the steady improvement in living standards across society.

The counter revolution against egalitarianism

Today’s crisis of living standards is, as I have argued, due in large part to the collapse of the egalitarian consensus, and its replacement by an anti-equality, pro-market ideology.

The New Right architects of this counter-revolution, which included the Conservative MP, Keith Joseph, one of Thatcher’s most trusted advisers, argued that egalitarianism had gone too far. Britain, they claimed, now needed a stiff dose of inequality to drive a more dynamic economy.

Far from the economic resurgence they envisaged, the effect of this shift has brought a new gilded age for the rich. This has come at the expense of a reversal of social gains, deteriorating life chances for many ordinary citizens, and a more crisis-ridden economy.

Many of the towering personal fortunes at the top – accumulated since the 1980s – have been largely unearned. As I have shown, they are less a reward for new wealth and value creation than the product of the upward extraction of existing wealth and corporate assets. Extraction, which was commonplace in the Victorian era, returned from the 1980s.

Contemporary examples of wealth extraction include manipulating corporate balance sheets, skimming returns from financial transactions (a process known as “the croupier’s take”) and the growth of monopolistic and anti-competitive behaviour by powerful corporations.

Extraction has been used to deliver excessive rates of return, boosting rewards to executives and investors, rather than raising corporate investment, long-term durability and productivity. From 2014 to 2018, FTSE 100 companies generated net profits of £551 billion, but returned £442 billion of this to shareholders, leaving a much lower proportion for wages and private investment. This has resulted in the steady decline in the share of the economy accruing to wages, down from the higher levels achieved after the war.

An influential study by the International Monetary Fund has concluded that high levels of inequality are associated with brittle economies and weak growth. A key reason has been a perverse system of incentives that makes it more attractive for executives to line their pockets than to build for the future. As economist Andrew Smithers has noted, this contributes to Britain’s low-wage, low-skill, low-productivity economy.

Rising inequality has also been shown to have significant negative social consequences. The voting gap between rich and poor groups rose from four percentage points in the 1987 general election to 22% in 2010. This has been fostered by political alienation and what political scientist Colin Crouch has called “post-democracy”.

In the decade before COVID, the gap in mortality rates between those living in the most and the least deprived areas widened. It now stands at 9.7 fewer years for men and 7.9 years for women.

Rebuilding Britain’s fractured society depends on re-embracing post-war egalitarianism. This means a set of pro-equality measures for modern times that raise the income and wealth floor but also lower the ceiling. Such measures should include a more generous benefits system financed by a more progressive tax system. They should also include the steady rebuilding of the social state.

Tackling widespread corporate extraction would further help to strengthen the economy for all. Part of Britain’s towering private wealth mountain should also be harnessed for the common good, with all given a stake in economic progress through a citizen-owned wealth fund.

Stewart Lansley does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.