The search for life beyond Earth dutifully continues. Astronomers using NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory, as well as the European Space Agency's XMM-Newton, are contributing some new research to the hunt — and hoping to lay the groundwork for future projects.

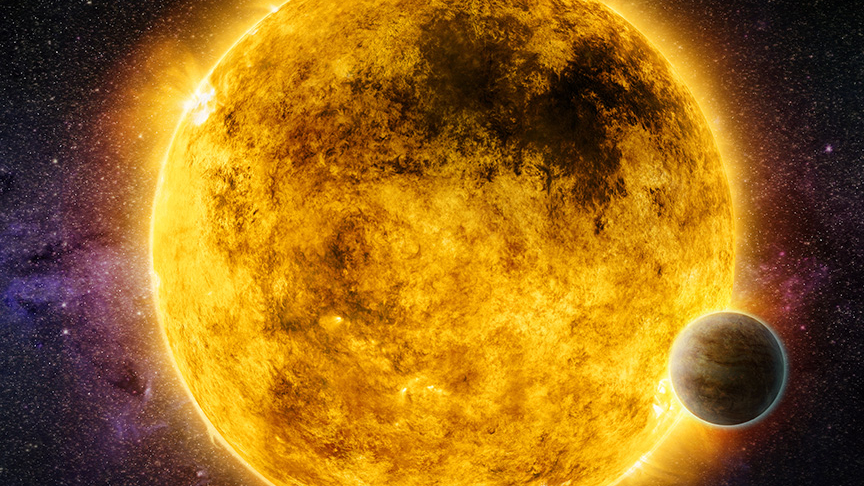

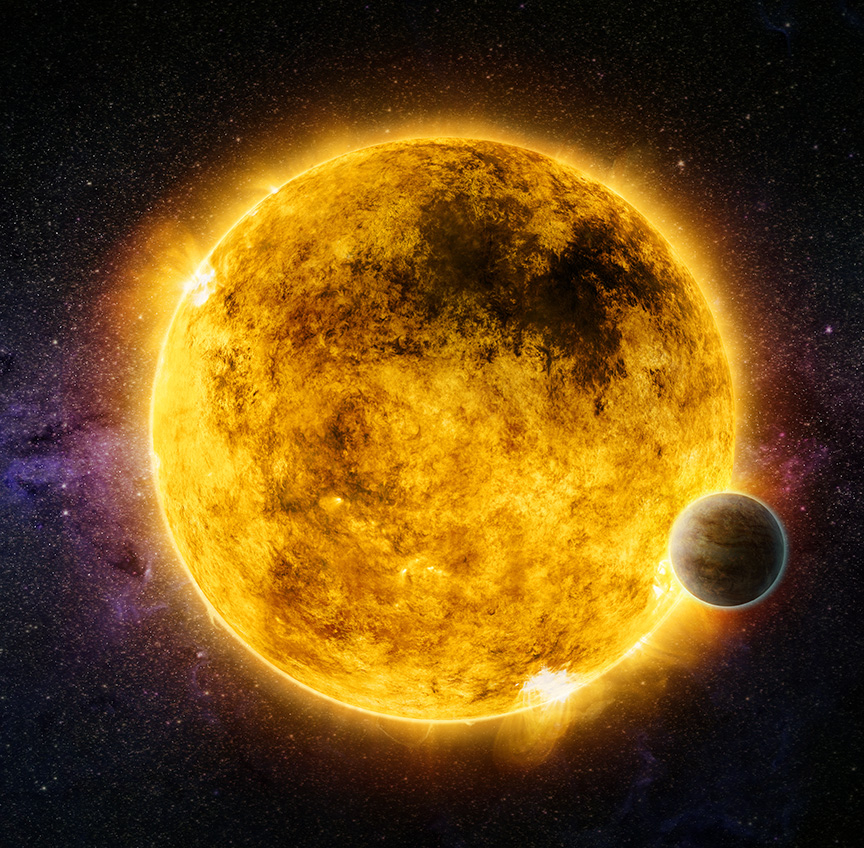

The researchers are using Chandra to study radiation emitted from nearby stars to establish whether or not an exoplanet orbiting those stars could be habitable. X-rays and ultraviolet light could, at high-enough levels, damage an exoplanet's atmosphere, reducing the possibility of supporting life (as we know it, anyway).

"Without characterizing X-rays from its host star, we would be missing a key element on whether a planet is truly habitable or not," astronomer Breanna Binder of California State Polytechnic University, who led this exoplanet study, said in a

. "We need to look at what kind of X-ray doses these planets are receiving."

So far, the team has studied 57 nearby stars, analyzing the brightnesses and energies of their X-ray emissions, as well how quickly their X-ray outputs change due to stellar flares. "We have identified stars where the habitable zone’s X-ray radiation environment is similar to or even milder than the one in which Earth evolved," research scientist Sarah Peacock of University of Maryland, Baltimore County said in the statement. "Such conditions may play a key role in sustaining a rich atmosphere like the one found on Earth."

Related: NASA space telescope finds Earth-size exoplanet that's 'not a bad place' to hunt for life

While only some of the 57 stars have known habitable exoplanets, there are likely many more habitable exoplanets out there — we just haven't found them yet. For context, we've discovered more than 5,500 exoplanets, but there are nearly 10,000 more candidates that are undergoing evaluation. Ultimately, there are likely billions of exoplanets just in the Milky Way galaxy alone.

"We don’t know how many planets similar to Earth will be discovered in images with the next generation of telescopes, but we do know that observing time on them will be precious and extremely difficult to obtain," said astrobiologist Edward Schwieterman of the University of California at Riverside. "These X-ray data are helping to refine and prioritize the list of targets and may allow the first image of a planet similar to Earth to be obtained more quickly."