Meghan, Duchess of Sussex, reportedly had it before marrying Prince Harry. Jennifer Lopez is also apparently a fan. We’re talking about a type of facial called a “buccal massage”.

But what exactly is a buccal massage? Does it really sculpt the face, as claimed? Are there risks? Could it actually make your skin look “looser” and older?

You probably won’t be surprised to hear there isn’t evidence from rigorous controlled scientific studies to show buccal massage gives you a more contoured look.

But talking about it can raise awareness about our facial muscles, what they do, and why they’re important.

What is buccal massage? Does it work?

Buccal massage (pronounced “buckle”) is also called “intra-oral” massage. The term “buccal” comes from the Latin “bucca” meaning “cheek”.

In buccal massage, a beautician inserts their fingers into the buccal cavity – the space between your teeth and the inside of your cheeks – to “massage and sculpt your skin from the inside”.

They apply pressure between the thumb (on the outside the mouth), and pinch and move fingers (inside the mouth), to stretch and massage the muscles.

You can also perform it on yourself, which may give you better control over stopping if it hurts.

But could all of this (rather expensive) action really change the shape of your face, or how it looks, feels, or moves?

It’s extremely unlikely, since the shape of your face is influenced by a lot more than your muscles. Any claims of buccal massage providing any lasting impact or “uplift” on the contours of the face are purely anecdotal.

In the absence of controlled trials reporting on the effects of buccal massage, it’s unlikely stretching your skin and oral or facial muscles in this way will provide any lasting benefit.

That’s possibly because buccal massage is “passive” – the muscles are only moving by the effort of the beautician.

In contrast, “active” movement of face muscles, through a program of face exercises, was associated with some improvements to facial appearance in a small study of middle-aged women.

Read more: Friday essay: the ugly history of cosmetic surgery

But facial massage and stretching can help some

External massaging or stretching muscles in the face, however, can help some people with certain medical conditions affecting the jaw, or how the mouth opens.

This includes people with trismus. This is when the temporomandibular joint – where the jawbone meets the skull – can be so tight it’s hard to open your mouth.

Face massage can also provide some relief for people with jaw clenching or bruxism (teeth grinding) when it relaxes the muscle and reduces tension.

Health professionals might also prescribe mouth and face stretches and exercises for someone recovering from facial burns. This is to make sure that, as someone heals, their skin is flexible and muscles mobile for the mouth to open wide enough and move properly. Being able to open your mouth wide enough is vital for eating and tooth brushing.

Read more: Why do I grind my teeth and clench my jaw? And what can I do about it?

Is buccal massage safe?

As there is no scientific research into buccal massage, we don’t know if it’s safe or if there are any risks.

The firm touch, squeezing and movement of another person’s fingers on the sensitive mucous membrane (moist lining) inside your mouth could be both uncomfortable and off-putting. This action will also stimulate your salivary glands to produce saliva, which you’ll need to spit or swallow.

As buccal massage involves a beauty therapist’s fingers being inside your mouth, infection prevention and control measures, including excellent hand hygiene, is essential.

It would also be interesting to know whether or not buccal massage could actually further loosen your skin and make you look older, sooner.

Read more: COVID or COVID vaccination can cause dermal fillers to swell up

Your face muscles are important

Regardless of whether buccal massage has any effect, it’s a chance to talk about our face muscles and why they’re important.

We often take them for granted. We may not think about keeping these muscles “supple”, and they don’t usually feel “stiff” unless we hold a smile for long periods, grind our teeth, or have a medical condition affecting the face, jaw or mouth.

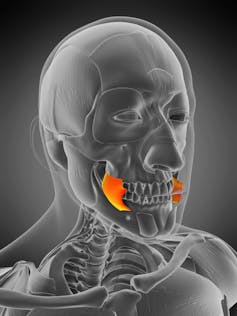

There are more than two dozen, muscles in our face, most in pairs, one on either side of the face.

They’re a vital part of who we are, shaping our appearance, and allowing us to make facial expressions, lower and raise our jaw and the corners of our mouth, smile, blow a kiss, speak, suck and swallow.

Face muscles help define the shape of our face and our identity. It’s no wonder we can struggle with age-related changes that affect how our face looks.

Read more: Let's face it, first impressions count online

3 cheers for our buccinators

The buccinator muscles, which buccal massage moves, are vital to our survival. The buccinator is one of the first muscles to contract when a baby suckles.

These muscles lie deep beneath the skin of the cheeks and are important for a number of reasons:

their main function is to help us eat. They contract to help move food between the teeth for chewing. We can squeeze our buccinator muscles to push food back into the mouth from the sides

they help us puff out our cheeks, blow out a candle, or blow a trumpet

when they contract, they move your inner cheek out of the way of your teeth. Without them, you’d bite your cheek every time you closed your jaw

they help keep your teeth in place.

In a nutshell

Buccal massage mightn’t make your face look “sculpted”. It probably comes with infection risks, and we know little about its safety.

But if nothing else, the buccal massage trend has highlighted just how important our face muscles really are.

Bronwyn Hemsley receives funding from the Australian Research Council and the University of Technology Sydney

Amy Freeman-Sanderson receives funding from he University of Technology Sydney.

Helen L. Blake does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.