If you’ve ever looked up at the night sky and felt a sense of awe at the enormity and mystery of the universe, you’re not alone. We humans are curious animals, but understandably focused on our day-to-day existence.

Looking up at the stars gives us valuable perspective. It reminds us that everything familiar to us, all our aspirations and problems, are confined to a tiny speck in one of trillions of star systems, nestled among hundreds of billions of galaxies.

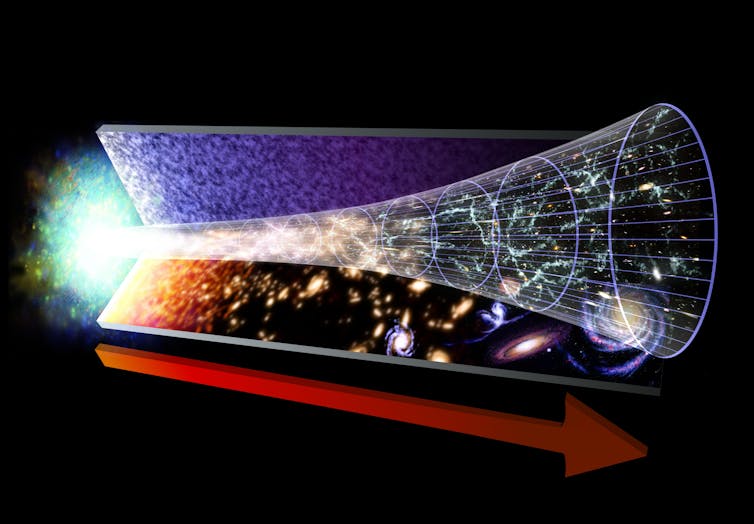

The science of cosmology deals with that vast, inconceivable expanse out there, beyond the precious, fragile home we call Earth. It is concerned with answering the biggest questions in science. How exactly did everything come into existence? Was there anything before the Big Bang? How did we get from there to the huge complex universe we see today?

These questions reference fundamental aspects of how the cosmos works, yet they’re also the source of vigorous debate. An increasing number of inconsistent measurements have even caused some observers to question whether cosmology is a field in crisis.

Over the next few weeks, our experts will delve into some of the longstanding debates, bringing their own perspectives to the table and drawing on the latest research and ideas. In the first article, the astrophysicist Andreea Font argues that whether “crisis” is a fair description or not, the field certainly seems to be at a tipping point.

A recent scientific meeting at the Royal Society in London, called “Challenging the standard cosmological model”, brought some of those arguments to the fore. The cosmological model in question is called Lambda-CDM, where CDM stands for cold dark matter. It is the most accepted framework for describing the structure and evolution of the universe. This is because it gives a good account of what scientists can actually observe, such as the structure of galaxies and the abundances of different elements.

But, as the Royal Society meeting revealed, there are important disagreements. Even though scientists can agree that the universe is expanding, measurements of how quickly it is happening do not align. One type of measurement for the expansion rate relies on bright pulsating stars called Cepheids and supernovae as distance indicators. The other depends on studying the “afterglow” of the Big Bang, known as the cosmic microwave background. Working out the expansion rate of the universe at this early stage of its evolution allows cosmologists to predict the current rate.

The discrepancy between these two approaches is significant and has been dubbed the “Hubble tension”. Perhaps there are holes in scientists’ theories of the cosmos. Or maybe the problem lies with the methods themselves. But this is no mere wrangle over numbers. The Hubble constant is a key to working out the age of the universe, as well as understanding its history.

As to what’s causing the expansion of the universe to accelerate, many researchers think it’s something called dark energy. If so, this form of energy is the dominant component of everything out there, making up 68% of the observable universe. Yet despite the obvious importance of dark energy to the bigger cosmological picture, we don’t really understand what it is or what its other properties are. For instance, is dark energy a constant, or has it varied over time?

If dark energy has changed over time, it might pose challenges for the Lambda-CDM model. Whether or not cosmology is in crisis, such uncertainties can lead to exciting discoveries.

The opportunities for new scientific results will be facilitated by new observatories due to come online in the next few years – especially if the James Webb Space Telescope is anything to go by. Since launching in 2021, the space observatory has shown us the earliest and most distant galaxies ever seen. They include one that existed less than 300 million years after the Big Bang, when the universe was just 2% of its current age.

What has astonished researchers is how bright these galaxies are considering their early ages. The brightness could even point to early bursts of star formation. Yet these distant objects shouldn’t have been able to evolve so quickly after the Big Bang, according to existing models of galaxy evolution.

Such areas of scientific enquiry are so fundamental to our understanding of the big issues that new developments can totally change our perspective on existence. At the very least, a better appreciation of the big questions can make looking up at the night sky an even more wondrous experience than usual.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.