Fossil fuels have provided a crucial source of energy over the past 200 years. But they also account for 75 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, enable massive environmental destruction and support many brutal regimes.

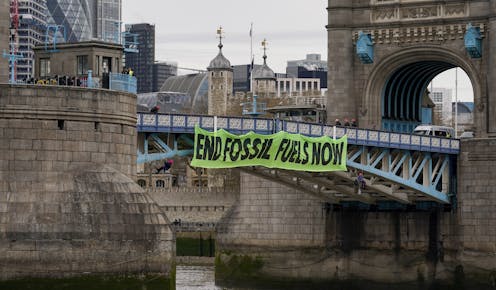

The United Nations climate change conference, known as the Conference of the Parties (COP27), begins Sunday in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, offering countries and organizations yet another chance to push for a phasing out of fossil fuel production. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting sanctions have made this move both urgent and challenging.

As researchers working on climate change and resource governance, we believe that new initiatives like the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance (BOGA) and rising support for a Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty — which aims at addressing the threat posed by fossil fuel production — can help build momentum towards phasing out fossil fuels.

A managed fossil fuel phaseout offers a chance for producers — including governments, corporations and unions — to negotiate the terms of a ‘just transition’ to renewable energy that includes retraining workers, addressing lost income, securing new forms of energy and diversifying fossil fuel dependence economies.

COP26 opened the doors for a phaseout

The Glasgow Climate Pact, that emerged out of COP26 last year, called upon parties to “accelerate efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power and inefficient fossil fuel subsidies, recognizing the need for support towards a just transition.”

The COP26 also saw the launch of the BOGA through which governments like Costa Rica, Denmark, France, Greenland, Ireland, Québec, Sweden and Wales can pledge to either phase out the production of fossil fuels, commit to a production phaseout with a legislated end date for existing production, or make looser commitments.

So far, no government with significant fossil fuel production has joined BOGA or endorsed the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty initiative, a fast growing civil society initiative calling for an end to new exploration and production, a fair phaseout of existing production and a just transition for fossil fuel workers, communities and producing countries.

Having tracked through the Fossil Fuel Cuts Database which countries had previously adopted initiatives to curtail fossil fuel production, including moratoria, divestments, carbon taxes or subsidy phaseouts, we tried to determine which of them might join an international coalition for a managed phasing out of fossil fuel production.

Who may join the phaseout coalition?

Using the Fossil Fuel Cuts Database, we tested economic, political and climate vulnerability factors against initiatives already taken between 2006 and 2019 by 124 governments with fossil fuel reserves. We found that dependence on fossil fuel rents reduces the likelihood of constraint measures, but not the size of fossil fuel reserves or production. Richer countries are also more likely to use constraints.

Based on our findings, we sketched seven main categories of countries for building up a global phaseout coalition.

The first and most likely members of such coalitions are middle and high-income countries with democratic regimes, active domestic climate movements and fossil fuel reserves of little significance to their economy. This has been the case of most of BOGA’s members.

The second category includes small countries that have no fossil fuel industry and are highly vulnerable to climate change impacts, such as the republic of Vanuatu in Oceania, the first state to officially support the Fossil Fuel Non-Proliferation Treaty.

The third category comprises countries with little prospect of fossil fuel production compared to major stakes in a green transition, such as Chile, a leading copper and lithium producer.

A fourth category includes high-income democratic countries with significant fossil fuel production but a diversified economy, such as the Netherlands, which shut down some of its natural gas fields.

A fifth category comprises countries where fossil fuel production is almost exclusively serving domestic energy markets that are slowly decarbonizing. China, India and the U.S. — the three biggest coal burners — have considered phasing down their coal production, but are yet to sign the Powering Past Coal Alliance — a coalition of national and sub-national governments, businesses and organizations working to advance the transition from unabated coal power generation to clean energy.

A sixth category includes countries that are highly dependent on fossil fuel revenues but still interested in accelerating their economic diversification, such as Saudi Arabia, the world’s largest exporter of crude oil, which embarked on an ambitious economic diversification plan. But, like with many other fossil fuel rich countries, this plan largely relies on fossil fuel revenues to finance diversification and a green transition, thus sustaining the paradox of increased production to pay for a planned phaseout.

A seventh category comprises low to middle-income countries with a high level of dependence on foreign aid, foreign direct investment and fossil fuel revenues. These countries face challenges when translating fossil fuel wealth into inclusive forms of development and often become even more indebted. Compensating them for leaving their fossil fuel reserves has proven challenging. However, some countries like Colombia may at some point decide to join a coalition following initial pledges to keep fossil fuels in the ground.

The right incentives can mobilize institutions

An agreement over a managed fossil fuel phaseout will not only help reduce emissions, but also help producers move away from the harmful effects of fossil fuel revenue dependence.

With the right kind of economic and political incentives, including support for economic diversification and energy security guarantees, a phaseout agreement could attract producing countries and mobilize key organizations, including the International Energy Agency, the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the World Trade Organization.

The next two COP meetings taking place in Egypt and in the United Arab Emirates will play a crucial role in increasing pressure to phase out fossil fuels, expanding the number of BOGA members and starting substantive discussions on processes and principles for an international fossil fuel phaseout agreement.

Philippe Le Billon receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Päivi Lujala receives funding from the Academy of Finland.

Nicolas Gaulin does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.