The search for solutions to climate change is reminiscent of the tragedy of the commons, where neighbours benefit from shared goods, such as an area of pasture or an irrigation pond, but their overexploitation ends up degrading the shared resource. Faced with a situation that harms everyone involved – in this case, out-of-control greenhouse gas emissions – the actors are unable to reach consensus positions that guarantee the common good, ie. limiting global warming to below 2 ℃.

To address this “tragedy”, the United Nations will host the 27th summit on climate change (COP27) in Sharm el-Sheikh (Egypt) from November 6 to 18.

What are COP meetings and what are they for?

In 1992, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, better known as the Rio Conference, established the Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), among other agreements. The summits known as COPs (Conference of the Parties) are some of the instruments that attempt to reach binding international agreements on emission reductions.

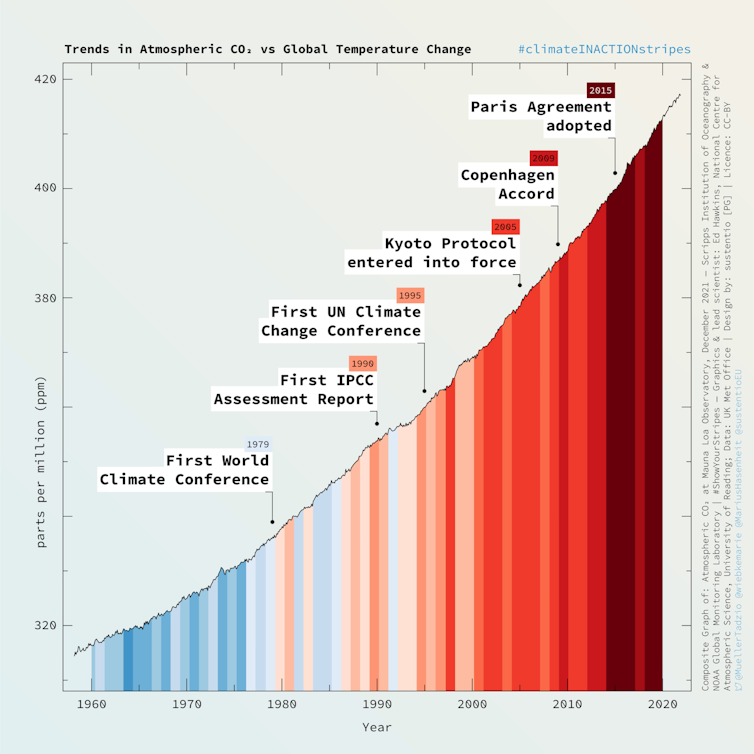

The UNFCCC has hosted an annual COP, from the first one in 1995 in Berlin to the 26th in Glasgow last year. Perhaps the most famous COP was the third (COP3), in 1997, which established the Kyoto Protocol: a set of commitments to achieve the decarbonisation of society and limit the damage from climate change.

Another particularly important COP was COP21, held in Paris in 2015. Countries there signed an agreement to limit global warming to 2 ℃. It also included the aspiration to limit it to 1.5 ℃.

What happened at COP26?

Last year’s COP is considered by many to have fallen short of its expectations, but some progress was made.

A firm commitment on zero emissions by 2050 was expected, in order to maintain the possibility of limiting global warming to 1.5 ℃. This required a 45% cut in emissions in 2030 compared to 2010 emissions. However, the agreements signed set us on a path for an average temperature increase of about 2.4 ℃.

Last-minute negotiations were particularly frustrating, as the term “phase out” of carbon was changed to “phase down” just before the negotiations were due to close.

Another key issue at COP26 was how to finance clean development in poorer countries and how to compensate them for the damage they have suffered because of climate change, for which more industrialised countries are responsible. At COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, a climate fund of $100 billion per year was pledged for developing countries from 2020 onwards. The current figures are still far below that target.

What can we expect from COP27?

This year’s COP is seen as the one that will bring concrete actions and commitments on emission reductions and also on the financing of losses and damages resulting from climate change to the global south.

It has been called the “African COP” because important commitments are expected, in particular for the African continent. It’s one of the most vulnerable continents to climate change from an environmental and social point of view, but paradoxically one of the least involved in the historical accumulation of emissions.

Despite agreements at previous COPs, the UN estimates that emissions in 2030 will be higher than in 2010, which eliminates the possibility of limiting warming to below 2 ℃. COP27 is therefore expected to be the one where effective emission reduction policies are implemented.

The risk of greenwashing

COP27 is also expected to make significant progress in the fight against tropical deforestation. Terrestrial ecosystems are essential in the fight against climate change, absorbing 25% of greenhouse gas emissions.

But we must be vigilant that the possible establishment of the Forests and Climate Leaders’ Partnership (FCLP) does not end up being a propaganda strategy or greenwashing that would allow big business to continue to emit while hiding behind uncontrolled and unmonitored tree plantations, which often generate more environmental damage than benefits and undermine the interests of indigenous communities.

Impact of the war in Ukraine

The war in Ukraine has highlighted Europe’s vulnerability due to dependence on fossil fuels and the need to rethink its energy model. After decades of calling on developing countries to grow through renewable energy, Europe’s energy crisis is forced to be exemplary and to make a firm commitment to non-fossil fuel energy. Otherwise its credibility and opportunity to influence the global energy transition will be undermined.

It is also foreseeable that the US will try to reinforce its technological leadership by promoting ambitious initiatives and gain the ground lost during the previous administration.

Another possible consequence of the war is whether the resulting new geopolitical status quo will affect emissions. In addition to the traditional influence of Western countries, China has a growing presence in Africa, which may encourage important agreements to strengthen its position on the continent.

Is international cooperation really possible?

COPs are often experienced with a certain optimism and excitement before they begin and with disappointment after they close. Replacing the main source of energy -fossil fuels- and the current short-term economic growth model is extremely complex. The outcome will not be known until the end of the 12-hour meeting on the final day.

Whatever the final outcome, the scientific community has a key role to play in rigorously documenting the impacts of climate change, the future risks for different regions and integrating the social perspective with the ecological one. Different studies show examples of possible consensus solutions to avoid overexploitation of shared resources and, ultimately, tragedy.

Víctor Resco de Dios receives funding from MICINN and the European Commission.

Miguel Angel de Zavala finances his research with funds from the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and the European Commission (H2020).

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.