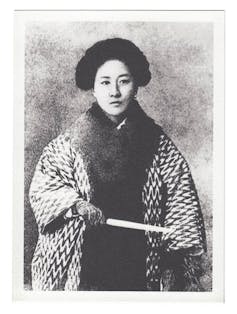

The British Museum has had to apologise after a translator’s words were used without permission. Writer and translator Yilin Wang shared on Twitter that their translations of work by the Chinese feminist poet Qiu Jin appeared in the museum’s exhibition, China’s Hidden Century, without consent.

The museum’s subsequent press release cited “unintentional human error”. It explained that it had corresponded privately with Wang and had now offered a fee for the use of the translations. Along with the Chinese poems, these were then removed from the exhibition. But the removal of the texts has also fuelled criticism of the museum, and sparked a debate about the role of translators.

Translation and copyright

Literary translation is legally recognised as an act of original artistic production. This means that translated literary texts enjoy their own copyright status, independent of the source texts. While Qiu’s work is now out of copyright because she died in 1907, Wang’s translations are not.

The role of original creativity in translation practices is frequently ignored or underestimated. It’s common to talk about reading “author X” rather than “translator Y’s translation of author X”. Even the Nobel Prize conveniently sidesteps the role of translators and their creative work when it confers its annual literary honour.

Recently, however, literary publishing has increasingly recognised the role of translators. In 2016, the International Man Booker Prize announced it would now split winnings evenly between the author and the translator. Translators are gaining visibility and it is becoming more and more difficult to pretend they don’t exist.

Read more: International Booker Prize 2023: our experts review the six shortlisted books

Translations are creative acts that take place in specific cultural contexts. They transform source texts into new, original literary works, and they can advocate for the source text and writer by introducing them to new readers.

Wang has written about the power dynamics of literary translation, including the barriers to access and participation faced by translators who are “outsiders” and translators of colour. In their essay writing, they draw specifically on their experience of systemic prejudice while translating Qiu Jin’s poetry.

They describe translation as an act of “reclamation and resistance” – and talk of the barriers they and others face finding a career in translation.

Like a translation, a museum is not neutral or objective. The objects and texts on display have been deliberately selected and positioned together. Just like the objects they frame, the words in a museum belong to someone and they have been chosen to tell a particular story.

Museums increasingly face pressure to reflect on their processes of acquisition and their contested ownership of items. This latest mistake – and handling of the fallout – shows that they also need to be transparent about the origins of the words they use to build the stories they tell.

From a “hidden century” to hidden texts

Removing items from display is not standard practice for the museum. The museum made a public statement in 2020 that it would not remove “controversial objects” from display. A section of the website dedicated to “contested objects” explicitly engages with the provenance of some of its most famous pieces, such as the Parthenon marbles.

But now Wang has described the museum’s response as “erasure”, and Wang argues, it has troubling implications, both for the museum’s critical engagement with its own curatorship and for the power dynamics of its relationships with non-white contributors.

The British Museum said in a statement: “In response to a request from Yilin Wang, we have taken down their translations in the exhibition. We have also offered financial payment for the period the translations appeared in the exhibition as well as for the continued use of quotations from their translations in the exhibition catalogue. The catalogue includes an acknowledgement of their work.” Wang contests this.

Meanwhile, the story has not gone away. It has been reported in the Chinese and French media, and Wang’s still developing Twitter thread about the discovery has been shared over 15,000 times.

As momentum grows behind the criticism of the museum, it is a good time for all of us to consider how we value and engage with the work of translators, whose creative labour allows us to access worlds and imaginations far beyond our own.

Caroline Summers does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.