Martin Puchner’s Culture: A New World History examines “the history of humans as a culture-producing species”. At the core of this statement lies the humanities, which emerges as a collective discipline “through a desire to revive a newly recovered past – more than once”.

Review: Culture: A New World History – Martin Puchner (Ithaca Press)

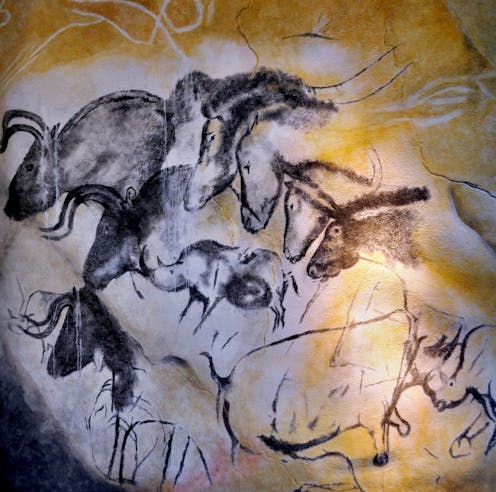

In his introduction, Puchner qualifies this idea through the case study of the Chauvet Cave in the south of France, where elaborate rock art dating back approximately 30,000-37,000 years was discovered in 1994. He reflects on the creation of this ancient art across generations, and the recovery of its remnants by new generations.

Culture is thus defined as a process of creation through transmission, and revival through discovery. This in turn

means focusing on special places and institutions of meaning-making, from the earliest marks left by humans in places like the Chauvet cave to human-made cultural spaces such as Egyptian pyramids and Greek theaters, Buddhist and Christian monasteries.

As far as a general audience is concerned, Culture delivers. It is well written, nuanced and light in style, spinning a series of historical narratives in an erudite and engaging way.

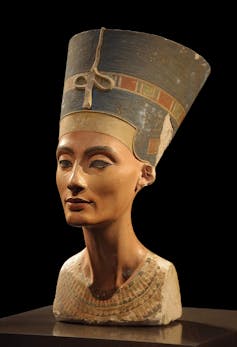

The history is broad in scope. Each of the book’s 15 chapters focuses on a different cultural space and time. It begins with Queen Nefertiti (c.1370-c.1330 BCE), and ends with Nigeria declaring its independence from Great Britain in 1960.

Puchner takes us through his case studies, interweaving each with attendant stories to show that no discrete culture owns its historical narrative completely.

Rather, each narrative is created from cross-pollination or hybridisation, as different peoples have moved in and out of space and time, adding their own blueprint. Every culture is shown to have an immense backstory of influences, contaminations, revisions and reinventions.

Read more: Friday essay: Simon During on the demoralisation of the humanities, and what can be done about it

Cultural interaction

A particular focus in Culture is the creation, preservation and transmission of culture through writing, translation and art. These processes, according to Puchner, have entailed travel, trade and global interactions.

In Puchner’s stories, we meet a host of fascinating historical characters. He gives an account of the excavation of the sculptor Thutmose’s workshop, which unearthed arguably one of ancient Egypt’s most iconic artefacts: the famous bust of Nefertiti. This, in turn, leads to a discussion of Nefertiti and her husband, the pharaoh Akhenaten, experimenting with monotheism.

There is the Muslim sultan of Delhi, Firuz Shah Tughlaq (1309–1388) – a man with a passion for architecture, inspired by his discovery of a mysterious stone pillar, which he eventually retrieved from its isolated location and brought to Delhi.

And there is the epic journey of the Chinese Buddhist explorer, Xuanzang (602-664 CE), author of the Great Tang Records on the Western Regions, which Puchner describes as “a classic in cultural mobility”.

Puchner is not naïve about the realities underpinning his stories of cultural interaction, replete as they are with colonialism, destruction, theft, and getting it wrong as much as getting it right. A particularly poignant case study in this respect is Tenochtitlan, the floating Aztec city founded c.1325, which was besieged, looted and destroyed by the Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés (1485–1547) in 1521.

This reality check reminds us that we need to do better than we did in the past. Recovery means more than wilful and ambitious archaeological practices. It means more than class-riven scholars locking up the artefacts of antiquity for the eyes of the intelligentsia only.

Recovery is about the constant striving towards “getting it right” and communicating with the broader community. It entails educating the next generation, entrusting them with the preservation of “human inheritance”, so they may proceed with “humility”.

The necessity of education

Puchner is interested in the creation of repositories for histories, religious texts, and literature in the form of academies, monasteries, libraries, and even studioli (“little studios”).

He discusses the necessity of education – written and spoken – as a mechanism of preserving culture. His book considers the examples of Plato’s Academy (the first western university); the House of Wisdom, also known as the Grand Library of Baghdad, from the Islamic Golden Age (c.8th–13th centuries CE); and the scriptoria or “writing rooms” of the Benedictines, the Christian order founded by Saint Benedict in the 6th century.

Puchner’s heroic tales of creative and intellectual interaction are chronicled in historical artefacts and documents, such as The Pillow Book by Sei Shōnagon (c. 966–c.1017). Shōnagon was lady-in-waiting to Fujiwara no Teishi, empress consort to Emperor Ichijō. The Pillow Book is a hybrid text in the form of a diary, which includes stories, anecdotes, gossip, poems and character portraits.

Shōnagon’s adventures become the basis of Puchner’s discussion of the extensive Chinese influence on the culture of the Japanese court – a discussion that is additionally fascinating because the information gleaned from The Pillow Book comes from a female perspective.

Methods and paradigms

While Culture makes for some thought-provoking reading, not all of the chapters are consistent or clear in the presentation of ideas. The chapter on Plato, for example, shows Puchner to be out of his depth, with ideas not always meshing. His accounts of the Egyptian influence on Greek culture and Plato the young playwright falling under the spell of Socrates and turning to philosophy are messy and uncertain.

Puchner nevertheless challenges us not to get caught up in the traditional Western paradigm of the ancient Greeks as the creators of culture. As he observes, the Egyptians considered the Greeks to be latecomers, compared to their own monumental history.

His chapter on Rome, which is overtly concerned with the Greek influence on Roman culture, adds little to this extensively researched topic. The intriguing story of a statue of Lakshmi, the Hindu goddess of prosperity, which somehow voyaged from South Asia to Campania and was eventually unearthed at Pompeii, though delightfully narrated by Puchner, gets lost along the way.

While some chapters, such as the one on Nefertiti, are smooth and coherent, others (Puchner’s discussion of the Muslim philosopher Ibn Sina’s dreams of Aristotle, for example) could have been better established by a consideration of the function of folklore and aetiological myth in cultural history. A closer reflection on the system of syncretism as a historical methodology, now regularly contested by academics, would also have been beneficial to Puchner’s project.

Despite its charm, Culture does not present anything new, particularly to scholars who are deeply engaged in the varied and intricate history of cultural transmissions. Unfortunately, and perhaps inadvertently, the book gives the impression that it is the first to consider cultural hybridisation in a dynamic global context – an impression augmented by the notes, which are light on the vast scholarship on the theme.

This incorrect impression is not helped by the publisher’s hype around the book, which declares: “Puchner argues that the humanities are (and always have been) essential to the transmission of knowledge that drives the efforts of human civilization.”

This is an argument that has been made many times before.

Marguerite Johnson does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.