Presidential elections are complicated.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia hold simultaneous elections in November. The states and the district certify those results.

But that’s not the end of it.

When people cast votes, they’re actually voting for a group of people called “electors.” Groups of these presidential electors meet in December. They send their votes along to Congress, which counts them in January. The presidential candidate who gets the majority of electoral votes is, finally, declared the winner.

There are known weaknesses in these rules for how we administer presidential elections and tabulate results in Congress. Ambiguities in existing law have been exploited to try to make something go wrong. Legal theories were floated by allies of President Donald Trump after the 2020 election that suggested ways to undermine the results of the election, culminating in a failed insurrection at the Capitol.

That’s why a bipartisan group of congressional leaders now aims to pass reforms to the 1887 law governing this process, the Electoral Count Act, before the end of 2022.

As an election law scholar, I have suggested that Congress focus its reforms on a few crucial areas that could have wide bipartisan support. It’s done just that.

Discouraging mischief

Both the Senate and the House have versions of a bill that tries to achieve the same end. But the Senate bill, known as the Electoral Count Reform Act, is narrower, went through extensive public vetting and has broad bipartisan support. It is likely something very close to this version becomes law.

The Electoral Count Reform Act does many small things, but it does a few big things that deserve public attention for their ability to deter mischief in this important process.

I testified at a Senate committee hearing on the legislation at the invitation of two co-sponsors of the bill, Sens. Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, and Roy Blunt, a Republican from Missouri. I have also spoken with members of Congress about its importance.

Here are the four major reforms in the bill:

1. Clarifies that Election Day is Election Day

Right now, presidential elections take place on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November. But existing law also allows states to choose presidential electors on a later date if they “failed to make a choice” on that day. This provision was designed in the mid-19th century for the few states that held runoff elections if no candidate received a majority. But no state uses it for that purpose today.

The provision leaves an open question: When has a state “failed to make a choice”? Some advocates in 2020 suggested that abstract questions about voter fraud or absentee ballots constituted such a failure and therefore meant the state could choose electors at a later date. That raised the prospect that states might send two sets of electors to Congress, a slate for the candidate who carried the popular vote and another slate, chosen later by the legislature. And that would invite Congress to undermine the popular election results by counting the second set of electoral votes.

Congress would close that door in the Electoral Count Reform Act. There would be one day of choosing electors, with no possibility of a later choice. And state legislatures could not show up after the election and attempt to change the rules – the bill mandates that state rules for how the election is run must be on the books before Election Day.

Ensures timely, accurate appointment of electors

In past years, especially in 2020, disputes about which votes should or should not have been counted raged on for weeks after Election Day. A federal court in Pennsylvania, for instance, rejected a lawsuit claiming that hundreds of thousands of absentee ballots cast in the 2020 presidential election should be thrown out because counties processed them differently from one another. The Electoral Count Reform Act would create a firm date for states to certify election results. Creating a firm deadline would ensure a speedy end to any litigation.

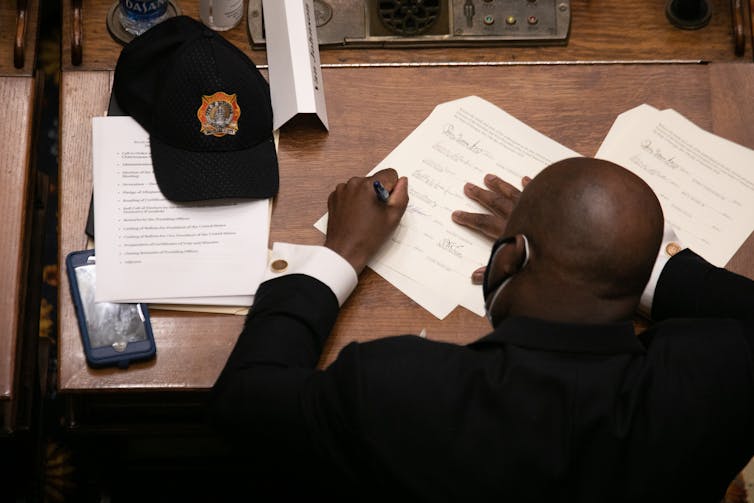

Some Trump supporters in 2020 attempted to file rogue paperwork purporting to represent an alternative slate of electoral votes from a particular state. The act would limit such mischief through expedited judicial review and clear obligations for state officials to submit accurate results to Congress. It would require state election officials to certify only the result that matches the outcome of the election held on Election Day, and nothing else. The act would ensure that there is one true set of returns from the states.

Raises objection threshold

When Congress meets on Jan. 6 to count electoral votes, it is typically a ceremonial act. But since the 2000 presidential election, some Democratic and Republican lawmakers have objected or attempted to object to counting at least some electoral votes cast in presidential elections. Debate proceeded in 2005 and 2021, which forced the chambers to separate and conduct two hours of debate over whether to count electoral votes.

To open debate currently requires just one member of each house of Congress to object. The act would raise the objection threshold to one-fifth of the members, based on the principle that only under the most extreme circumstances should Congress consider refusing to count electoral votes.

It is simply too easy under the existing rules to cause mischief and turn this ceremony into an airing of grievances. Raising the threshold makes it harder to slow down counting and increases public confidence by refusing to give attention to baseless objections.

Defines vice president’s power

In 2021, Trump publicly and privately pressured Vice President Mike Pence to refuse to count electoral votes during the joint session of Congress. Pence would not do what Trump wanted, arguing he had no power to do so.

The act would clarify that the role of the president of the Senate – typically, the vice president – is ceremonial. The language would be updated to reflect what is already known – the vice president has no unilateral power to determine whether to count electoral votes.

While some of these concerns have been around for many years, they have come to prominence only in recent years, and none more so than around the violent attacks that took place when Congress last counted electoral votes.

If Congress enacts these simple bipartisan solutions, it can instill confidence in future presidential elections.

Derek T. Muller does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

.png?w=600)