The coach approved the postgame stop at the 7-Eleven, agreed to the purchase of the beer, even signed off on the conversion of his hotel room into a speakeasy for that beer’s consumption. And drink his players did, well into the Shenandoah night, spilling out into the hallway on account of their delegation’s high spirits and in spite of their low numbers—numbers that, as we’ll see, are part of this story.

Around midnight the commotion roused a hotel guest, a woman who confronted the presumptive adult in charge, who stood in that corridor wearing a T-shirt and black boxers.

“May I ask what you’re doing?”

It’s said that Pete Carril, the Hall of Fame basketball coach who died Monday morning at age 92, sent a cloud of cigar smoke her way before delivering his answer: “I’m wallowing in success.”

That moment was uncharacteristic of the man who presided over the program at Princeton for nearly three decades. No coach more hastily declared virtually every one of his 525 victories “ancient history.” Yet Princeton’s 55–50 win at Virginia 47 years ago deserved a little wallowing. It’s a game from which he was ejected, yet years later he would call “the highlight of my life as a coach.” It carries a lesson for teachers of all types, and stands as a worthy lens through which to look at the life and coaching career of Pete Carril.

On the morning of Feb. 25, 1975, Carril’s Tigers had headed to Charlottesville in a strange psychological limbo, at once gaining confidence and wobbling in their faith. They had strung together six wins in a row thanks to a core of average-sized upperclassmen that included future NBA guard Armond Hill, as well as Mickey Steuerer, Tim van Blommesteyn, Brien O’Neill and Peter Molloy. A couple of rapidly maturing big men, Barnes Hauptfuhrer and Lon Ramati, supplemented them with size and muscle. But only one weekend of Ivy League play remained, leaving Princeton with quailing hopes of claiming the conference’s automatic bid to the NCAA tournament.

The Tigers had split their home-and-home series against Penn and stumbled at Brown. Lagging a game behind the Quakers, Princeton knew that even a sweep of Brown and Yale on the final weekend of conference play would mean little unless Penn lost to one of the same two opponents. And without winning at least 20 games, the Tigers weren’t likely even to land a bid to the National Invitation Tournament, which still held prestige during an era when the NCAA field accommodated only 32 teams.

Worse, Princeton had traveled south exhausted and depleted. The game was set for the Monday after the Tigers negotiated the Columbia-Cornell bus trip, the Ivy’s toughest. The team took only nine players because of injury and illness. Except for a trainer and a team doctor, Carril would be the only person on the bench in civvies. He feared the trip would be such a fool’s errand that he had dispatched his top assistant, a former Princeton player named Gary Walters, to check out a high school prospect in Kentucky, while his other aide, Bob Dukiet, coached the Tigers’ freshmen against the Army plebes.

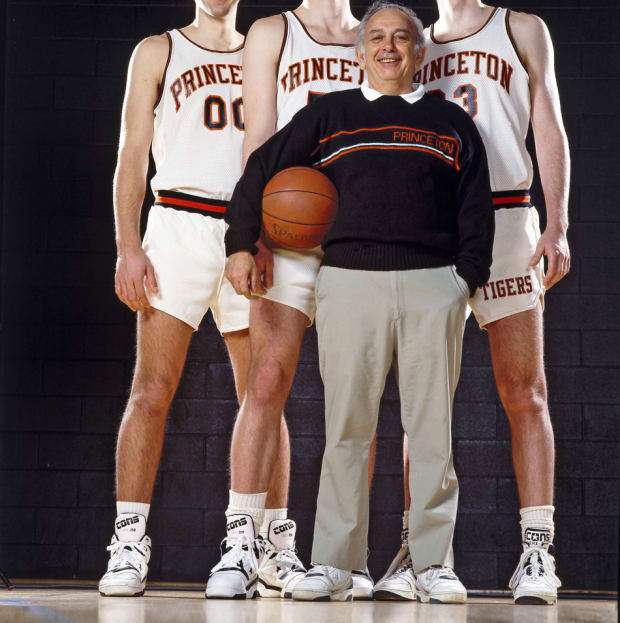

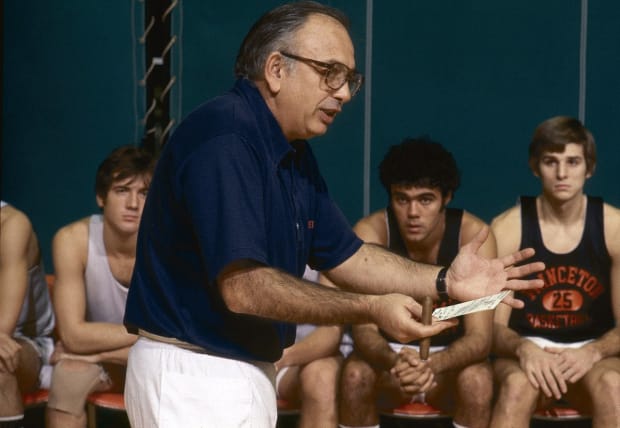

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

So, still weary after the eight-hour ride back from Ithaca, the Tigers flew from New Jersey that morning to the seat of Mr. Jefferson’s University, where not 36 hours earlier Virginia had beaten nationally ranked North Carolina. Late in the afternoon, the Princeton players took their pregame meal, then filed out of the hotel to board the bus for the short ride to University Hall. In the parking lot an impeccably groomed woman began to heckle them. “She was maybe mid-forties, a Southern belle, but one of these rah-rah, Wahoo Virginia fans,” Hauptfuhrer remembers. “She was saying things like, ‘Our Cavaliers are gonna whoop up on you folks to-night!’ I guess she was expecting Coach Carril to say something back. Coach just stared at her. She waited for him to say something, but he kept staring. Finally she got uncomfortable and turned to walk away. That’s when Coach yelled, ‘Hey!’ She turned back around like she’d had a shock to her system, and he went, ‘Grrrrrrrrr!’ We watched all this while getting on the bus, laughing so hard we were guaranteed to come out loose.”

Taking the floor before the customary Virginia sellout, Steuerer couldn’t help but notice the Cavaliers’ bench—“an endless line of players,” he remembers, with lieutenants in matching orange blazers flanking coach Terry Holland, then in his first season at the school. Many of the 7,450 fans in the stands wore orange too, but only a scattering matched theirs with black, Princeton style.

The two teams spent the first eight and a half minutes shadowing each other, which emboldened the visitors, who knew the long odds Princeton faced by drawing a homestanding Atlantic Coast Conference power for what was a third road game in four nights. Hauptfuhrer sank an 18-foot jumper that pulled the Tigers to within a point at 11–10.

And that’s when the lights went out.

Suspicious by nature, Carril believed someone on the Virginia bench had signaled an electrician to break whatever spell was causing the home team’s slow start. After a 20-minute wait for the mercury vapor lighting to come back on, play resumed with Virginia inbounding the ball on the sideline—whereupon van Blommesteyn darted in front of the pass and sailed in for a layup. On the Cavaliers’ next possession, Hill poached into the passing lane on the wing to make a steal of his own, scoring another layup. The first boos tumbled from the upper reaches of the home team’s roundhouse arena.

Hill picked off another pass and converted, and moments later he swanned in for two more points after another steal. When van Blommesteyn added yet one more steal and layup of his own, Holland, furious, called timeout to rip into his guards, who seemed still to be basking in the defeat of Carolina over the weekend. The Cavaliers’ coach subbed in an entirely new backcourt. “The first play after that timeout, they throw another pass to the wing,” Molloy recalls. “And Timmy intercepts it too and goes in for another layup.” The Tigers ended the half with an 11–2 stretch. Turning six stolen passes into snowbird baskets, they left the floor with a 31–21 lead. The second half would deliver even more remarkable events. But of those first 20 minutes Holland would later say, “I’ll never watch something like that again. If I have to, I’ll get thrown out myself.”

Pete Carril was born in Bethlehem, in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, in 1930 to a father who had emigrated from Spain to work in the steel mills. A coal yard across the street served as young Pedro’s childhood playground. First in high school, then at Lafayette, he played run-and-gun, the furthest style possible from what he would become known for as a coach. By ’67, Princeton had seen its two high-profile Bills kite off to the NBA: All-American forward Bill Bradley to the Knicks and coach Bill “Butch” van Breda Kolff to the Lakers. On van Breda Kolff’s recommendation, the school hired Carril, who had just finished coaching his first collegiate season—a losing season—at Lehigh.

During Carril’s early years, Princeton played an offense lively enough to produce, in Geoff Petrie and Brian Taylor, NBA and ABA rookies of the year, respectively. But by the mid-1970s, escalating tuition costs and the Ivy League’s longstanding refusal to permit athletic scholarships began to price the Tigers out of the market. As he struggled to attract first-rate athletes, Carril chose to hunker down. He developed a set of offensive principles based on the old “pivot play” popularized by Dutch Dehnert and the Original Celtics back in the ’20s. His teams would wait out an opponent, carefully moving the ball around the perimeter, until a defender, lulled or careless, turned his head. Then, suddenly, some Tiger would “pull the string” and cut through the open middle to the basket, taking a pass and converting a layup.

Carril’s teams would go on to use “the Princeton Offense” to engineer a series of signal NCAA tournament victories and near-misses, most notably a one-point, down-to-the-wire first-round loss against Alonzo Mourning and Georgetown in 1989, which until UMBC’s upset of Virginia in 2018 was as close as any No. 16 seed had come to upsetting a No. 1. But the final victory of Carril’s career—the game that seared him into the minds of the public and probably ensured his enshrinement in the Hall—was Princeton’s 43–41 upset of defending-champion UCLA in the first round of the ’96 NCAA tournament. Victory came on a backdoor layup in the dying seconds, after Carril, during a timeout, had urged forward Gabe Lewullis to circle back and try “pulling the string” again if he couldn’t at first get his defender to bite on a backcut. That’s precisely how Lewullis freed himself for the winning shot, a basket that became a monument to Carril twice over: as the Tigers’ signature play, to be sure, but also as a demonstration of the stubborn faith their coach placed in it.

Carril detested praise, both the collecting and dispensing of it. “The cheapest kind of reward,” he called it. Late in his final season, right after Princeton had held Dartmouth to 39 points, someone asked him about his team’s defensive performance. Carril sensed a trap. Surely Dartmouth deserved no praise, but he had found plenty to be desired in his own team’s play. The coach’s answer was a rhetorical backdoor pass, threaded past the premise of the question to score a point of its own: “They have guardable players. And we guarded them.”

Throughout his career, Carril used his working-class beginnings as a touchstone. He made an obsession out of the truism that material comfort rarely confers advantages on those who play basketball. The game instead rewards guile and deception, traits bred on city streets and at lower social strata. So he brought the sons of cops and firefighters and holders of union cards to the Ivy League school. He didn’t consider basketball to be a builder of character; it was instead, he believed, a revealer of it. How someone played the game told Carril everything he needed to know. Indeed, his greatest flaw was a tendency to believe that a player came to him with character fully formed, and thus it wasn’t always worth the effort to change him for the better.

In Carril’s worldview, beer had its place. He considered it a restorative drink, the reward due a man after an honest day’s work. He winced when he saw his players eating candy. Children ate candy. He wanted his players to be men, and men drank beer. This veneration of proletarian life helped him survive on an Ivy League campus—to cope, as a Sports Illustrated headline once put it, with being “a blue-collar coach in a button-down league.”

Like van Breda Kolff before him, Carril in 1996 nominated his own successor. He did so with an ad lib at a postgame press conference after clinching the league title at the end of his final season, declaring that his longtime assistant, Bill Carmody, would replace him—“after a brief search.” (At this, Gary Walters, by now Princeton’s athletic director and nominally Carril’s boss, watched from the back of the room with the blood draining from his face.) Two years later, under Carmody, the Tigers lost only twice and were ranked No. 8 in the country. The season’s emblematic moment came in Madison Square Garden, during a defeat of Niagara in the ECAC Holiday Festival, when Princeton scored every one of its 21 field goals on an assist. With the Tigers briefly flummoxed by the Purple Eagles’ switch to a zone defense, Carmody called timeout. In the huddle, his players looked at him searchingly. Carmody could have been channeling his old boss when he told them, “You’re smart guys. You figure it out.”

Neil Leifer/Sports Illustrated

The home team’s sluggish start, the blackout, the ease with which Hill and van Blommesteyn made sport of the Virginia guards—all combined to make for a bizarre first half. But the strangest moment came slightly more than five minutes into the second, after which the Princeton players were indeed left to “figure it out.”

Virginia’s offense involved running its All-American forward, Wally Walker, off a series of screens to spring him free. Until late in his career, when they played virtually nothing but zone, Carril’s teams rarely conceded any pass, and the man guarding Walker on this night, Hill, contested every cut and fought through every screen. As the Cavaliers struggled to catch up, Walker became more and more frustrated. Finally the two stars’ private battle came to a reckoning. Walker cut off a back screen. Hill scrambled over its top, beating Walker to his intended destination on the wing. That’s when—in the Princeton telling, anyway—Walker shoved Hill out of the way, sending him, as Hauptfuhrer remembers it, “under the scorer’s table.”

Referee Lou Moser had to blow his whistle. But then Moser, a veteran ACC official, did something that left the Tigers in disbelief. He ruled not that Walker had shoved Hill, but that Hill had shoved Walker, thereby committing his fourth foul. What happened next, Steuerer says, was “like out of a movie.” Carril flung his program to the floor and lit out after Moser “with his full Spanish red temper on high,” Hauptfuhrer recalls. “He was already in a foul mood from the lights going out. When this happened, his cork popped.”

After the game, Carril would sound Churchillian in his indignation, calling Moser’s call “the most flagrant act against fair play I’ve seen in 20 years.” But his response in the moment was a cartoonish stream of profanity that left his players so slack-jawed they failed to perform the task that normally fell to Princeton’s absent assistants—restraining the head coach so he wouldn’t get tossed.

No transcript exists of exactly what Carril said to earn his only ejection in 29 seasons. But according to the recollections of several players, Moser whistled the first technical foul after Carril called him a cheater. He whistled the second after Carril called him a redneck. In those days it took three, not two, T’s for a coach to get ejected. And so:

“Say one more word and I’ll give you a third!”

“You’re a @#$%*&%^$# cheating redneck!”

“It was funny, really,” Molloy recalls. “It was like when you tell your kid, ‘Say one more word and you’re grounded,’ and your kid says, ‘Word!’ Coach really did do everything but slug the guy.”

Once Moser had banished him, Carril began to consider the consequences. “He wouldn’t leave,” Steuerer says. “We’re like, ‘Coach, you’ve gotta go.’” But Carril believed he couldn’t go—not so much because he had no assistant to coach the team, but because he didn’t want to leave his players to the tender mercies of someone he considered to be “a @#$%*&%^$# cheating redneck.”

As it happened, the other official whistling that night’s game—college basketball hadn’t yet adopted the three-man officiating crew—was a veteran well known to the Princeton party. Hal Grossman worked often in the Northeast, and Carril had actually grown up with him in the Lehigh Valley. “Hal sort of calmed me down,” Carril would recall years later. “Said I was embarrassing him. That’s sort of why I agreed to leave the court.”

A couple of Princeton players clearly remember one other thing Grossman told Carril: “You tell your boys to hustle. If they do, they shouldn’t have anything to worry about.”

Carril appointed Molloy, a 5'10" junior reserve from Merrick, N.Y., as acting coach and took his leave. A calm quickly settled over the bench. “Carril wasn’t the world’s greatest game coach, because he’d get so worked up that smoke would be coming out of every orifice,” says Richard Stengel, another reserve guard on that team. “What struck me was how calm and focused Peter [Molloy] was. It’s like with horses: If you’re calm, they’re calm. He spoke clearly and softly and told us to do the simplest things.”

Before departing, Carril ordered the team to give up its aggressive man-to-man and instead play a 1-2-2 zone, with Hill planted safely at the point to avoid his fifth foul. Then, flanked by security guards, the coach took up position in a tunnel leading from the court.

Molloy says he faced only one difficult decision the rest of the game: whether to sit Hill down or risk that fifth foul. But Steuerer disputes this. “Lon Ramati hardly ever took a shot, and within 30 seconds after Coach gets thrown out and we decide we’re slowing it down, Lonnie jacks up a turnaround airball from 20 feet,” he says. At that, Hauptfuhrer remembers looking over at Carril in the tunnel and seeing the coach draw an index finger across his throat. Whether or not the team’s new player-coach saw the gesture, Molloy made his move, replacing Ramati with O’Neill, a guard, and ordering the Tigers into a forerunner of the Princeton Offense.

In January, Carril had installed the alignment, a four-guard set he then called “the Open Offense,” to cover for his team’s lack of size. By late February, it had evolved from a jerrybuilt fix into an effective weapon. If they seized a lead, Carril would sit Ramati, as erratic a foul shooter as he was an offensive player. With Hill, Steuerer, van Blommesteyn and O’Neill or Molloy arrayed around the sweet-shooting Hauptfuhrer, Princeton would prosecute each possession with patience. Controlling the ball, snapping off passes and cuts, staying wide to keep the lane vacant (hence the name “open”), they waited out backdoor opportunities and spotted up for jump shots if a defender became too mindful of his flanks. The Open Offense had an additional virtue: Four guards created at least two mismatches. “No forward was fast enough to guard Armond [Hill] or Timmy [van Blommesteyn],” Molloy recalls.

And so Princeton minded the clock—the game clock, for the shot clock hadn’t yet been introduced. The Tigers’ 35–29 advantage upon Carril’s ejection flowed to eight and ebbed to two but never entirely evaporated. Molloy called only two timeouts, the first with 5:11 to play. “It was either to remind the guys that we were trying as much as possible to hold the ball,” he would say years later. “Or it was just to catch our breath. There were no TV timeouts back then.”

The game turned on a moment right after the first of those stoppages. Since Carril’s ejection, Grossman had served as Princeton’s guardian angel. “If there were 15 close calls down the stretch, we must have gotten 14 of them,” Molloy says. “Grossman would step in and wave the other ref off.”

With slightly more than four minutes remaining, the black stripes on Grossman’s shirt looked more than ever like those of a Tiger. Hill drove down the gut of the Virginia defense, flipping in a shot while sending the Cavaliers’ Mark Newlen into a heap on the floor. You couldn’t find a more explicit charge in an indictment, and Lou Moser stood poised to make the call. But Grossman freight-trained on to the scene. He whistled a block, counted the basket, and sent Hill to the free-throw line, where he added the point that pushed Princeton out to a 48–40 lead. Hill’s full-contact layup would be the Tigers’ final field goal of the game. From there the Cavaliers could only foul, and Princeton sank seven of 11 free throws, including a couple by Molloy who, after van Blommesteyn fouled out with 2:20 to play, had finally put himself in the game.

Lane Stewart/Sports Illustrated

As Princeton’s victory became more likely, several Virginia fans gathered along the railing overlooking the tunnel to bait and throw things at Carril down below. “Policemen chased everyone back to their seats,” the coach recalled in 2001, still sounding surprised that the cops had afforded him any protection at all. By the time the buzzer sounded, he had already retreated to the safety of the Tigers’ locker room, where he greeted his jubilant players. “Muggs [Molloy] and Mickey [Steuerer] were soaking their knees in ice,” he remembered. “Everyone was asking, ‘How in heck did we ever do this?’ There was a moment of silence, and Mickey said, ‘Well, we finally got ourselves a coach.’”

Firing up a cigar, Carril met the press to make the case of a man wronged. “My guy got pushed 20 feet,” he said, “and they called the foul on him!” Then he urged reporters to interview “our real mastermind.”

“The kid wants to be a coach,” he said of Molloy. “I’m trying to get him to be a lawyer. He’s got 1520 board scores and his old man is spending 6,000 bucks to send him to Princeton. To do what? To be a coach?”

The Tigers swung by that 7-Eleven on the way back to their hotel, making sure the cashier knew the lettering on the marquee outside—a pregame message that still read “CAVS OVER TIGERS”—needed revision. Then the team repaired to Carril’s room. “The beer went in the bathtub,” the coach recalled. “And they sat me up on the bed, like a king.”

A year later, Molloy, the Tigers’ coach-in-a-pinch, would find himself featured again, this time in one of Princeton’s tantalizingly unavailing efforts in the NCAAs. With his team up a point and four seconds to play, the Scarlet Knights’ Eddie Jordan fouled Molloy, a 90% free-throw shooter, sending him to the free-throw line for a one-and-one. Rutgers called a timeout, and another timeout, desperately hoping to preserve with some magic spell an unbeaten season that for the moment lay out of its hands. Finally, Molloy squeezed off his shot, the last competitive one of his life. It clanked off the back of the rim.

Afterward Carril and his one-time understudy headed to the coach’s favorite dive, Andy’s Tavern, on the fringe of campus. Together they drank beer into the small of the morning. “Believe me,” Molloy says, “more people remember Rutgers than remember Virginia.”

But considering how it fit into the grand scheme of Princeton’s 1974–75 season, the Virginia game should earn Molloy a more flattering kind of immortality. That victory in Charlottesville, followed by a sweep of Brown and Yale the following weekend, did win the Tigers, despite an 18–8 record, a place in the NIT, where they took out Holy Cross, South Carolina, Oregon and Providence in what became one of the program’s great accomplishments. For much of its postseason run, including most of the second half of the NIT final, an 80–69 defeat of the Friars, Princeton used the same offensive set that had so bamboozled the Cavaliers and would become Carril’s great legacy to the sport. “The crispness, the ball movement, the cutting, the way we broke the press—everything we did in Madison Square Garden [during the NIT] followed from that game,” Hill remembers. “The Virginia game began everything, with five guys being mentally together.”

A year later, the morning after the loss against Rutgers and suddenly free from Carril’s ban on facial hair, Molloy let his beard go. It lasted into the next century. He did leave Princeton with the vague idea of becoming a coach, and briefly signed on as an assistant at his old high school on Long Island, St. Agnes Catholic School in Rockville Centre. But as Carril would have it, Molloy wound up going to law school, and then into the title insurance business in Mineola, N.Y., where he and his wife raised four kids. He limited his coaching to CYO ball. Over the years, Molloy became amused at how often his old coach would mention that game he failed to finish. “I think it became part of his shtick,” Molloy says, “because the story’s not really about him.”

Of course, in the end, the story is entirely about him—about how soundly he taught the game. Is it any wonder that a Chicago-based team composed of various former Tigers, including Barack Obama’s brother-in-law Craig Robinson, became a perennial three-on-three champion, regionally, nationally and even internationally? As Carril conceived and imparted it, the Princeton Offense was basketball at its most stripped down. By the end of the century, it had spread throughout the sport, with teams at every level adopting its principles because they could be so effective, no coach required. “I’ve always said the test of a teacher is how the students do when the teacher isn’t around,” says Hill, who after a pro career installed the Princeton system as coach at Columbia and went on to win an NBA title in 2008 as an assistant with the Celtics. “He did such a good job drilling us. There were times he’d ask us to do things and we’d ask why. Against Virginia, we found out why.”

Or as Steuerer puts it: “We didn’t need as much coaching because we were older and pretty experienced. But it just goes to show that if you prepare properly, a game is no different from practice. It’s the team whose coach tries to get everyone all pumped up that’s in trouble, when you should really be doing just what you do every day.

“I don’t remember ever getting a motivational speech from Coach—anything like, ‘C’mon, play hard.’ Play hard is what you’re supposed to do.”

What Carril ceaselessly urged his players to do was play smart. “That game was the most beautiful display of knowledge I’ve ever seen,” Carril would later say of that February night, delivering himself of that rarest of things, a compliment. “The fellas played so smart, it was unreal.”

Praise may indeed be the cheapest kind of reward. And Carril’s long wallow in how smart his men played that night was, in a roundabout way, a kind of bouquet to himself. But with that game his pupils delivered a lesson of their own. He that by me spreads a wider breast than my own proves the width of my own, goes the stanza from the 47th section of Walt Whitman’s “Song of Myself,” a poem about teachers of athletes that Walters shared with each of his coaches after he became Princeton’s athletic director. He most honors my style who learns under it to destroy the teacher. . . . My words itch at your ears till you understand them.

The best teacher, Carril’s players demonstrated that night, is the one who engineers his own redundancy.