Although the importance of communication in fostering better relationships and solving problems is well-recognized, much focus has been placed on “talking it out” — while the role of listening tends to be overlooked.

“Compassionate listening” is critical to interpersonal and political communication, because without it, more talking can exacerbate the existing divides and misunderstandings.

Compassionate listening is a practice of shifting our focus from talking to listening. In so doing, we can overcome egocentricity. It helps us change habitual self-referencing to engage with the world from the perspective of others.

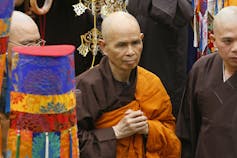

Compassionate listening can be informed by Buddhist philosophy and practice. In particular, it can take the form of “deep listening,” proposed by Thích Nhất Hạnh. He’s the late Zen Buddhist monk who initiated engaged Buddhism and illuminated for decades how to practice mindfulness in daily life.

Read more: Thich Nhat Hanh, who worked for decades to teach mindfulness, approached death in that same spirit

Deep listening

Nhất Hạnh emphasized the importance of deep listening, or what he called “compassionate listening.” He was referring to deep listening and compassionate listening interchangeably, because compassion is needed to listen to others deeply.

For Nhất Hạnh, deep listening means understanding the other person, and listening without judging or reacting.

In his book The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching, he wrote:

I am listening to him not only because I want to know what is inside him or to give him advice. I am listening to him just because I want to relieve his suffering.

He also explained that compassionate dialogue is composed of loving speech and deep listening, making mention of what’s known as “right speech” in Buddhism, which advocates abstaining from false, slanderous and harsh speech along with idle chatter:

Deep listening is at the foundation of right speech. If we cannot listen mindfully, we cannot practise right speech. No matter what we say, it will not be mindful, because we’ll be speaking only our own ideas and not in response to the other person.

When we listen deeply to better understand others, including their suffering and difficulties, we feel with them and compassionate speech comes more easily.

Compassionate listening also requires refraining from being judgmental while we listen. That doesn’t mean giving up engaging with what others say. Instead, it involves switching the focus from self to others.

Trying to understand when it’s difficult

Compassionate listening also involves a tension between the attempt to understand others and the acknowledgment of the limited ability to do so.

It requires a willingness and effort to understand others. As Nhất Hạnh put it, compassionate listening happens when we listen with the sole purpose to understand others. Underlying genuine deep listening is the genuine concern for others’ well-being: If we don’t care about others’ suffering, why would we listen to what they have to say?

In Buddhist philosophy, every being is interdependent and interconnected. In this light, caring for others is also caring for ourselves since our own well-being is interrelated to the well-being of others.

When we show compassion for others and help relieve others’ suffering, we actually help relieve our own suffering as well because in changing our focus from self to others, we start to see and learn to transcend our previously under-recognized greed, hatred and ignorance — in Buddhism, the three root causes of dukkha (suffering) that arise from self-centeredness.

Ultimately, caring for others and listening to them deeply is to practice compassion not only for others but also for ourselves.

But compassionate listening also requires the humility to acknowledge that we may not be able to fully understand others. Humility is crucial for communication, especially against backgrounds of broad diversity and growing inequalities in liberal democracy.

The humility to accept our limited ability to understand others, especially those who are very differently situated from us — along with the aspiration to better understand them despite our limited ability to do so — fosters and energizes ongoing communication across differences.

Equanimity

The Buddhist concept of equanimity can also be helpful.

In Buddhism, karuṇā (compassion) is not an overwhelming or reactive emotion, but is one among the “four immeasurable minds” – with the other three being loving/kindness, joy and equanimity. In the Buddhist tradition, equanimity is generally associated with non-attachment, or letting go of ourselves.

As Nhất Hạnh wrote:

The fourth element of true love is upeksha, which means equanimity, non-attachment, non-discrimination, even-mindedness, or letting go. Upa means ‘over,’ and iksh means ‘to look.’ You climb the mountain to be able to look over the whole situation, not bound by one side or the other.

He explained that equanimity doesn’t mean indifference, but is about detaching from our prejudices. He emphasized that clinging to false perceptions about ourselves and others can hinder us from arriving at a deeper understanding of reality and can lead to misunderstanding, conflict and even violence.

While compassionate listening seems passive, focusing on receiving what others say instead of interjecting to change the conversation is actually an active way to engage in the discussion. That’s because it involves actively looking into our own biases and prejudices, which can open up further possibilities to improve the conversation.

Compassionate listening means not only opening our ears to what others have to say, but also reflecting on and challenging problematic self-narratives that we carry with us. In fact, equanimity can reasonably be seen as an essential condition for genuine open-mindedness.

Listening for better communication

Compassionate listening has broad implications for interpersonal and political communication.

With the practices of deep listening, humility and equanimity, compassionate listening alerts us to the tendency to project ourselves into conversations instead of hearing the other person.

When we focus too much on what to say to persuade others while neglecting to listen deeply, talking can lead to more severe interpersonal tensions or exacerbate political polarization.

Compassionate and effective communication is listening-centred. Listening with compassion does not guarantee solving all problems at hand, but it does help us better understand problems from other perspectives — and to better support one another to address problems collectively.

Yang-Yang Cheng does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.