First contact between Māori and the French

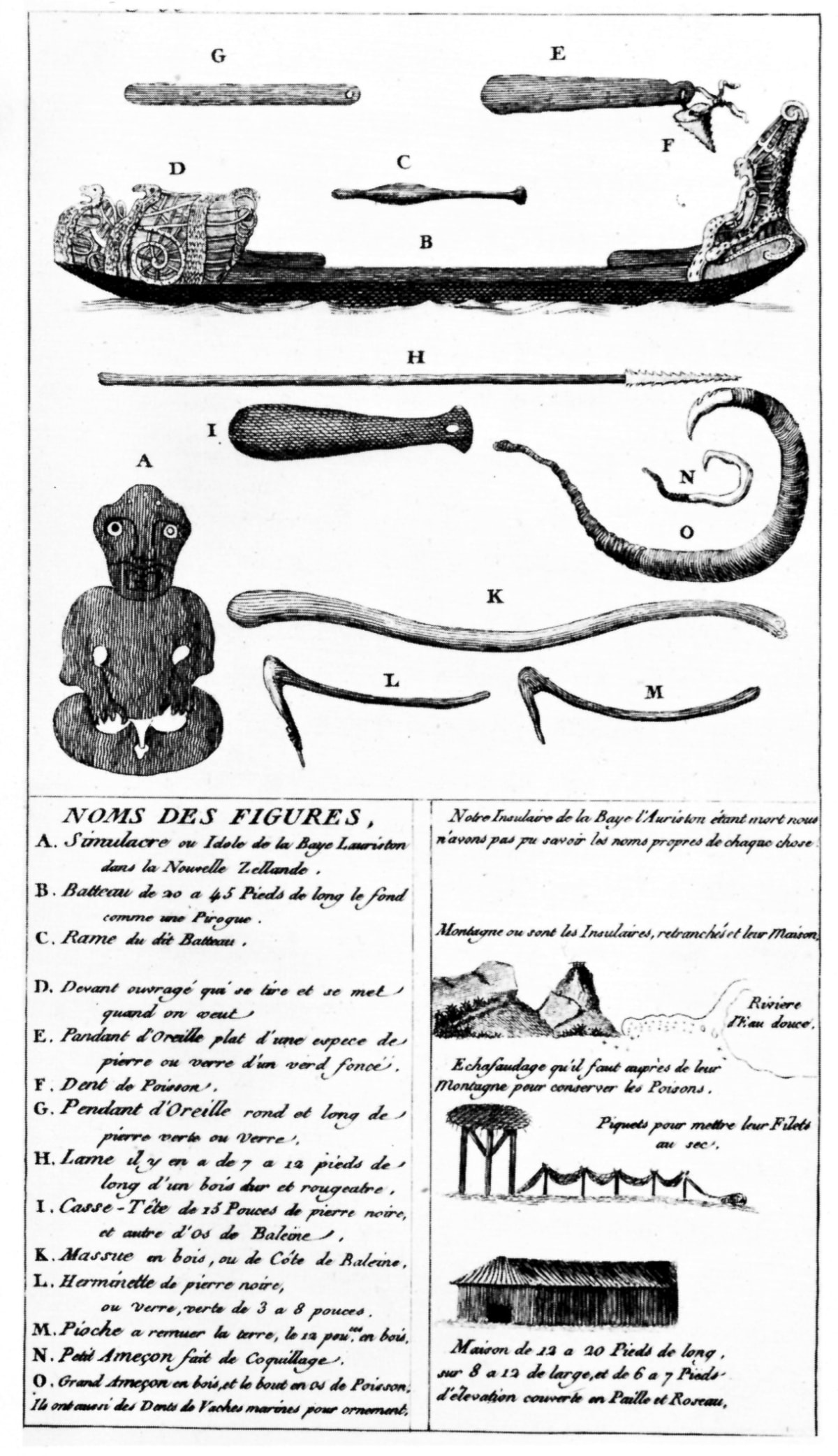

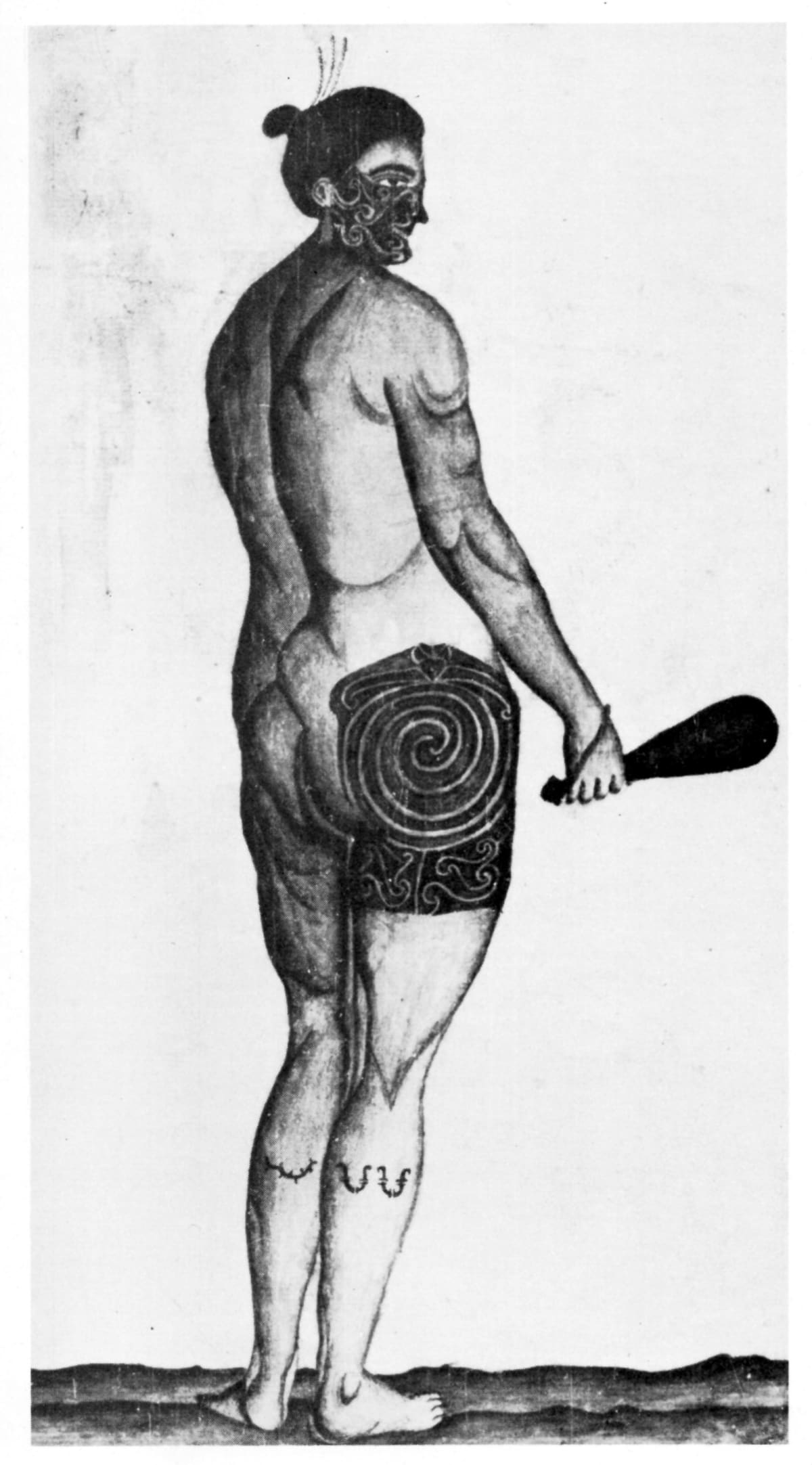

December 17, 1769: Solomon Islanders had looked fierce and been fierce; Māori looked less frightening and soon proved themselves hospitable to strangers. The French had their first glimpse of Māori after passing Surville Cliffs. One canoe, then several, came up to the St Jean Baptiste, bearing strongly built, confident looking, brown-skinned men whose hair was tied back in a top-knot. They were muscular, proud in their bearing, and bore large concentric tattoos on their faces and thighs. Above all they came as traders, bringing freshly caught fish to barter with the newcomers.

The sick crew were told that soon they would have a good meal, that the natives were peaceful, and that before long it would be possible to anchor. In their feverish state, the wretched sailors imagined they could smell the magic "land air" already rolling down into their stinking darkened quarters. For the first time in six weeks hope had returned, more effective by far than any of the remedies which the ship's surgeon could bring out of his depleted and inadequate store.

A chief was bold enough to climb aboard. Alone on the upper deck, watched at a distance by a group of gaunt sailors, he stared at the forest of rigging above him, the furled sails, the rising masts, and shook with wonderment. The sailors led him to de Surville who clasped him in his arms. In the main cabin he was offered food and brandy. He spat out the drink, as much in fear as in surprise, but ate the salt meat. Then de Surville gave him a pair of trousers and a vest, both of red cloth, and helped him put them on. In exchange, the chief presented de Surville with a dogskin cloak.

Thus the news could be sent down to the sick that a friendly exchange of gifts had marked the first contact between French and Māori.

When he stepped ashore the next day, it was as the first European to land on the shore of Doubtless Bay and the first white man the local Māori had ever seen.

They were kind to him. At dawn they came in their elaborately carved canoes loaded with fish. They traded under the stern gallery, the French sending down baskets on a line, lowering a length of red cloth and hauling back the fish placed in the baskets. Trade was pleasingly brisk: although the French were unaware of it, their choice of red cloth was a good one, red being a mark of rank in Māori society. Occasionally a basket would be sent back if the fish were too few or too small and the fisherman would make up the deficiency in order to receive his share of cloth. Soon many of the Māoriwere wearing their purchases thrown as a light cloak over their brown shoulders; while on board the smell of fish soup, of fish frying, of fish cooked in white wine, spread from the galley to the rest of the ship.

After lunch de Surville ordered a boat lowered, together with the small yawl he had bought in the Batan Islands.

He wrote, "I embarked a detachment of ten soldiers and gave a sword to each of the rowers, eight in number.... As we approached we could see numbers of natives spread out along the shore and on the nearby heights, as well as in a little fort, some waving a loin cloth from left to right, others a green branch, others a stick. We did not know whether these signs were favourable or not. Finally we reached the shore where the surf was breaking so that we were forced to use the grapnel and to disembark on the sailors’ shoulders."

A chief was there to greet him, his faced marked with the traditional tattooed patterns, deep blue on a brown complexion, a dogskin cloak over his shoulders, a heavy flat mere of greenstone tied to his wrist.

He put his hand out to touch the strangers and "offered me his nose: it is their manner of kissing". De Surville gestured to the water casks. The chief took him by the hand, leading him to a small stream running down from the heights. They then sat down on the bank, with the warriors in a semi-circle behind them and the soldiers standing on guard. Dried fish and herbs were brought and set down before them. De Surville ate a little fish and took the greens back to the ship — perhaps he guessed that some kind of vegetables had to be added to their diet if the sick were to recover.

Before he left, the Captain walked up to a clump of trees and touching a few gnarled branches gestured that he wished to cut them down for firewood and take them away. The chief nodded agreement. De Surville was taking no risks — he had no wish to anger the natives by sawing down a sacred tree.

The night was fine. Fires were visible on the heights and along the inlets, signs that the bay supported a large population. The cress and wild celery de Surville had brought back had contributed to a fish-based stew which the men had greatly enjoyed. Was it this, or the land air, or hope — or all three — which made the sick declare that they felt better and one or two come up on deck for the first time for a week and stare at the dark mass of the shore with its pinpoints of flickering fire? The cress and the celery certainly appeared to have amazing effects, bringing a flush to the cheeks and tasting like a heavenly food; but for some it all came too late: a slave from Madagascar died during that night of hope and was consigned to the waters of the bay.

The sun rose proudly in a clear blue, early summer sky. The longboat was lowered. Ten empty barrels were hauled down into it; then Monneron, de Surville and his nephew, and a detachment of soldiers and sailors, climbed down the rope ladder. The surgeon Dulucq helped some of the sick into the smaller boat, where he was joined by eight soldiers.

Māori were waiting on the shore as they had done previously, waving branches and weapons. The chief came forward, the rubbing of noses was repeated; but this time he asked the French to wait.

"I agreed to this and he went to discuss with various groups of natives gathered on the neighbouring heights; after which he returned to me and we walked together to the watering place."

Māori were beginning to wonder how long their visitors planned to stay and even whether they might not be contemplating some settlement

The men rolled out the casks and the woodcutters started work on the trees. The sick disembarked, walking slowly and painfully, helping one another along the beach and towards the long grass at the foot of the slopes, watched by the soldiers on duty and by Māori above them. At lunchtime de Surville offered the chief some roast pork, the taste of which greatly appealed to him — for he had to be prevented from taking it all. Farther off, seated on the lower slopes, the scurvy cases were eating the same food, with the addition of cress dipped in a vinegar and oil sauce prepared by the cook. Noticing the Frenchmen’s predilection for this greenstuff, a few young natives went off collecting it and brought it to them in large handfuls.

But Māori were beginning to wonder how long their visitors planned to stay and even whether they might not be contemplating some settlement. The ordinary routine of life was disturbed; the food situation might soon become unbalanced if the strangers continued to buy most of the fish they caught. When de Surville went back to the watering place the following day with the same number of soldiers and another 10 casks, but this time more sick — since the cress and celery were having a prompt effect and a greater proportion of the men were now strong enough to go ashore — "the chief came as usual but seemed less friendly".

He asked the Captain to wait at the shore’s edge, as he had done before, and went up to talk to the silent knots of men on the slopes, with yet more silent watchers on the heights above, where the village lay hidden and defended by ditches and stout palisades. When he returned, he made signs that the French were to return to their ship.

"I at once made it clear that I would not. Then taking me in his arms he urged me to wait a while and begging me to draw my sword, he also asked me to give it to him for a moment and told me that he would bring it back. I gladly gave it to him. He took it by the handle and, holding it upright, went back to each group. He returned and offered me his nose, making sign that I could advance to the watering place, which I did, taking the barrels, and set the woodcutters to work and brought the sick ashore."

The strange ceremony was repeated shortly after this. The chief again borrowed de Surville’s sword, this time going up to the pa on the hill. The Frenchman agreed — he was still protected by the soldiers’ muskets. Meanwhile the economic consequences of the Frenchmen’s arrival were becoming more evident: there was marked reluctance on the part of Māori to sell any more fish. Familiarity was also breeding minor annoyances. There were jostlings, laughter, catcalls, all directed at the sailors and at himself. By lunchtime de Surville was beginning to feel irritated: "An old man seated near the watering place harangued me ceaselessly in a loud voice, without making one single gesture that might make me understand what he was endeavouring to say. He annoyed me because he would not stop and kept on staring at me and talking."

One word seemed to emerge time and again from the ceaseless babble. Atua. Gods. Was the old priest calling on the gods to protect his people and drive the French away, or was he likening them to gods? Or was he — less politely but equally plausibly — calling them atua nga tangata: demons, enemies of man, harbingers of plagues and diseases? Whichever it may have been, de Surville complained to the chief when he came to lunch. Gestures made it clear that the old man was a person of rank, a priest or noble of some kind. De Surville told his servant to take some roast pork to him, then went over himself and tied a strip of red cloth to his lance. "From that moment he looked happy."

De Surville was prepared to make any reasonable concession to please Māori. That is why — even though in time he wearied of it — he was willing to trust the chief with his own sword. He had to refill at least a hundred water casks from the slow-running stream. And it was far easier to buy fish than to send his men fishing in a bay of which they knew nothing.

"With patience, we shall in time discover a great deal about this country. We already know far more about the people and their way of life than Tasman ever did."

De Surville changed the anchorage to bring the St Jean Baptiste closer inshore, reducing the distance the boats had to travel with the water casks. He was aware of the Māori's changing mood and he realised that it would be wise to reduce the length of the stay in Doubtless Bay. Accordingly that evening the St Jean Baptiste struggled against the tide and wind to anchor in eighteen fathoms facing the little bay where the French obtained their water and which de Surville named Chevalier Cove — thus both the main backers of the venture would be commemorated, and the jovial governor of Chandernagore could console himself, if the profits were low, with the thought that his name would appear on the maps of New Zealand.

The wind freshened during the night. By early morning it rose to a strong south-westerly gale — driving the ship slowly towards the shore, for the holding qualities of the bottom were poor and the anchor was slowly dragging over the bed of broken shells and sand. All the available men were on duty. The wind began to scream through the rigging, and the ship, after the stillness of the past few days, was once again creaking and rolling. One squall after another struck her. A salty damp, mingling with the urine of the last few pigs, once more ran down the companionways and seeped into the ’tween-decks.

De Surville lowered his only large anchor, paid out more cable, and the ship responded. A grey dawn was rising over the land, heavy with clouds and the threat of chilling rain. No canoes came out to the ship and no Frenchman went ashore. The men rested from their exertions, watching the white waves clawing the base of the cliffs.

The next day was calmer, if still cool, but now at least the heavy clouds thinned out and parted to reveal long strips of blue sky. The sea had moderated a little and the bay once more was alive. Canoes slipped in and out of the coves; men went fishing, and on the heights, inside the forbidden pa and behind its high palisades, where the French had glimpsed strangely carved, red-painted huts and sinister looking idols with extended tongues and eyes of mother-of-pearl, the women went about their mysterious tasks and the old tohunga brooded.

The canoes turned and made for the ship. The chief himself was paying a visit, accompanied by a crowd of warriors and this time by a few women. The wahines puzzled the French. Few among them were well enough to feel any interest in women. No doubt the women found it difficult to understand why the white men should be so listless. The French wrote them off as lascivious and impudent. Their dances, performed that day on the forecastle, were hard to interpret. Their arm movements were graceful enough, but the shaking of thighs and stomachs less so. The men watched impassively or with mild curiosity, their indifference exciting the women and driving them to unequivocal gestures. They were lewd; they were a nuisance; and they had to be kept away. De Surville was concerned about his men being led into some ambush. Nothing very serious could happen on board ship, but if a man, once he had recovered his health and vigour, were to be lured into the bush by some native woman, murder might ensue; and if several Frenchmen were tempted into taking such risks a whole boatload might be massacred. The women, therefore, had to be driven back to their canoes with yells and threats and if necessary with blows.

The men laughed and turned to watch the chief and his followers who had paid no attention to the scene. They were more interested in the guns. The metal, totally unknown in New Zealand, puzzled them as much as the possible use of such strange objects. De Surville attempted to explain their purpose. He showed them a cannon ball, brought it up to the mouth of a gun, said ‘boom!’ and raised the ball to his chest. Then he leaned back against the rail, his arms outstretched, his head on one side and his eyes closed.

The chief raised his patu, nodding his head.

"Fire the gun," ordered the Captain.

Two gunners loaded the gun, while de Surville pushed back the chief and, drawing a high circle with his arm, pointed to the open sea.

"He began to watch attentively, as well as those of his people who were with him on the quarterdeck. We fired and they were all very frightened. He was the one who showed the least fear, because he did not cease to watch attentively the spot where the ball was due to fall, and when he saw it causing the water to spout up to a great height he gave a loud exclamation and spoke to his men."

How many huge craft of this kind were there around the shores of Aotearoa and what upheavals and disasters might they not portend?

Some of the canoes, however, were speeding for the shore. The sound of the shot had echoed through the bay, sending up flocks of frightened seabirds whose cries of alarm were now resounding along the cliffs. It had boomed through tall grass and between the pohutukawa trees; and in the pa above, the women had fallen silent and the voice of the tohunga was stilled. What terror lay hidden in the bowels of that strange ship, from which a sudden thunder had emerged? What dangers did the presence of these white men herald? Had there not been another similar ship — more heavily built, but equally alien — which had sailed across the wide mouth of the bay a mere fortnight ago? No such ships had ever been seen before — whatever the legends might say about some other great canoe being driven off by warriors many generations ago. But now, how many huge craft of this kind were there around the shores of Aotearoa and what upheavals and disasters might they not portend? The heads of the elders were bowed and a strange fear seized them, the echoing warning of the unknown still rolling across the great bay.

De Surville, having established the superiority of his arms, wished to cement his friendship with the chief. He ordered two of his most precious possessions brought to him: two pigs. Māori had no meat to sell him, although they had offered him a dog, which he had refused, and it was clear to him that pigs would be of great value to a people whose main food was fish and root crops. "I showed him our pigs and gave him a young male and a young female, trying to make him understand that if he kept them he would have many of them from their mating. This seemed to please him greatly and he took them away with every sign of satisfaction." The sacrifice, for a ship whose food supplies were now tragically low, was a very real one.

By now the sea was moderate enough for the water party to return ashore. "The chief came with me instead of going in his canoe. On the way he urged me not to land at the usual cove, but to make for another, telling me by signs that there is more fresh water there." There was indeed a larger cove nearby with a deeper stream, but the beach was so pebbly that it would have been impossible to roll the full barrels over it. De Surville was also worried by the fact that the boats would be hidden from the ship by a headland and would not have the support of the guns in the case of trouble. He accordingly went back to his usual landing place — and there realised why the chief had tried to lead him away from it: "We made for our first cove where there was a large quantity of freshly caught fish. I think that this was what they did not want me to see. Since they share it among themselves and live on it I was doing them harm."

De Surville was again showing himself aware of something many other navigators did not understand — that the large-scale purchase of foodstuffs by a ship’s crew can present a real threat to a native population living at bare subsistence level. On this occasion, however, Māori agreed to sell a good part of their catch; nor were relations really strained because, when de Surville was again asked for his sword and, exasperated by this ceremony, refused to part with it, the chief was but slightly upset.

From almost every point of view the stay at Doubtless Bay had proved to be a success. Only a few more days were left in which trouble could arise, whether through Māori patience becoming exhausted or through some thoughtless action by the French — or by a set of circumstances no one could foresee or circumvent.

Taken with permission from a new edition of the 1970 classic The Fateful Voyage of the St Jean Baptiste: A true account of M. de Surville’s Expedition to New Zealand and the unknown South Seas 1769–70 by John Dunmore (Heritage Press, $39.99), available in bookstores nationwide.