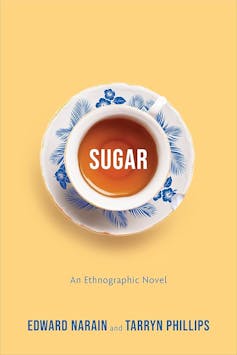

At first glance, Sugar: An Ethnographic Novel, by Edward Narain and Tarryn Phillips, may look like a relatively light holiday read: a murder mystery set in the glittering paradise island of Fiji.

But beyond the sweet (excuse the pun) cover and title, this novel tackles some serious issues including colonialism, globalisation, structural inequality, exploitative labour and trade practices, and Fiji’s diabetes epidemic.

Review: Sugar: An Ethnographic Novel – Edward Narain and Tarryn Phillips (University of Toronto Press)

Set in Suva, with a tropical cyclone looming, Sugar follows three strangers from different cultural backgrounds. They find themselves entwined in a brutal murder, a crime revealing inconvenient truths about the darker side of global development in Fiji.

Sugar is an ethnographic novel written by two Australian-based researchers: political analyst Edward Narain and medical anthropologist Tarryn Phillips, drawing on their respective research and lived experience.

Narain, a senior advisor with the Fiji Labour Party, is descended from Indian indentured labourers. He spent a lot of his childhood with Indigenous Fijians. Phillips has conducted ethnographic research alongside Fijian communities for over a decade on issues of poverty, health and social justice.

Three very different lives

Sugar follows the lives of three main characters in the lead up and aftermath of the cyclone: Hannah a naïve but well-intentioned Australian health volunteer, Rishika a jaded, Indo-Fijian, amateur historian, and Isikeli a troubled Fijian (iTaukei) teen caring for his diabetic grandmother. These three live very different lives, shaped by gender, class/caste and ethnic differences.

Young and hopeful Hannah, is a “voluntourist”. She works during the week on things she finds a bit boring and laborious, while partying and going away on weekends.

Isikeli is a young and troubled iTaukei (Indigenous) man, who lives in an informal settlement, also referred to as squatter settlement. He cares for his grandmother, who has diabetes, and his niece while his mother works away from home on one of the island’s many resorts. During the day Isikeli is one of the “coconut boys”, disenfranchised youth who collect and sell coconuts. By night, he is a petty criminal.

The story opens with Rishika at home, on the fifth day of mourning her husband Vijay – murdered while Cyclone Dorothy swept through the island. Rishika is an Indo-Fijian historian who put her career on hold when she got married. Her personal research into her family’s history – focusing on her Indian ancestors, brought as indentured labourers to work on Fiji’s sugar plantations under the British empire – is threaded throughout the novel.

In a racially motivated slur, Isikeli is accused of murdering Vijay. He then reaches out to Hannah for help. In her search for her husband’s murderer, Rishika ultimately enlists Isikeli’s help to catch the real culprit, proving Isikeli’s innocence along the way.

Indentured labour

Sugar: An Ethnographic Novel contributes to a tradition of Indian diaspora narratives being written by second-and third-generation migrants (such as Narain), often blending autobiography and fiction.

Sugar is still one of Fiji’s primary exports. According to the Fijian Health Ministry, almost one in every three Fijians has been diagnosed with diabetes. In their book, Narain and Phillips creatively use sugar as a lens through which to examine structural inequality over time, wrought by settler colonialism:

Rishika is thinking about sugar, the way it has sprinkled down through history. It has made people rich and propped up empires, like diamonds and cotton and gold. It has enslaved Indians on foreign shores and forged ethnic conflict between them and their hosts.

Rishika discovers that her great-grandfather was amongst thousands of Indians coercively recruited by the British colonial administration in the late 1800s and early 1900s to work on sugarcane plantations in Fiji, just as they were throughout colonies in Africa and the Caribbean.

The indentured labour system, created after slave labour was abolished, was suspended somewhere between slavery and wage-labour. Prospective labourers were offered the “dream” of moving to an island paradise, the opportunity to achieve social mobility away from India’s caste system, to earn money and return as wealthy men.

In reality, in Fiji Girmitiyas (the Indian term for indentured labourers) were treated by colonial settlers as distinctly different from other workers, in need of discipline and control.

While these labourers were technically paid for their work (by task, not hourly wage), the plantation overseers also controlled their housing and food supplies. No matter how much people worked, they would often end up in debt to their employers. And if they wished to return to their homeland, they would have to sign another five years to stay on at the plantation. This is sometimes referred to as the “dirty trick” of the indenture contract.

This pattern of violence was repeated by both the overseers and the husbands of the Indian women who were also brought to Fiji. The gendered violence enacted on the plantations became the blueprint for unequal and violent relationships between men and women in contemporary Fiji. Today, Fiji has some of the highest rates of domestic violence in the Pacific.

A highly stigmatised issue, family violence is referenced in Sugar, when Rishika recall’s her husband’s mother hiding bruises. She would cover them “by bunching and hanging her sari in particular ways; big purply-yellow reminders that dinner should be on the table at the right time”.

Sugar: An Ethnographic Novel is an elegant and intimate portrayal of everyday life in Fiji, deeply honest about the struggles and inequalities often hidden beneath the tourist-centric image of an island paradise and showing its beauty in all its complexity.

Emma Quilty does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.