Over the last few years, many parts of the world have been devastated by extreme droughts, floods, wild fires and heatwaves linked to climate change. But climate change is not only influencing our weather: it also poses an existential threat to the outstanding universal value (OUV) of many of the world’s most precious sites on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, and potentially to the World Heritage system itself.

This year is the 50th anniversary of the World Heritage Convention, one of the most successful international conventions. It was adopted in 1972 to protect globally significant heritage places as a common heritage of humankind. Renowned World Heritage sites include the Taj Mahal, the Great Wall of China, Yellowstone National Park and the Galápagos. The convention has been signed by 194 countries (known as states parties). More than 1,150 sites in 167 countries have been inscribed on the World Heritage List for their cultural and/or natural values. On average, around 25 more sites are added to the list at each of the annual meetings of the World Heritage Committee, even as existing sites come under threat from climate change.

Climate change is now the most significant threat to many World Heritage sites, especially those inscribed for their natural values. Short- and long-term climate-related impacts are increasing. For example, by 2100 and depending on the emissions scenario used, complete glacier extinction is predicted for 8 to 21 World Heritage sites, within which glaciers are an attribute of their universal value. The number of African coastal heritage sites at risk from a 100-year extreme flooding and coastal-erosion event, including the Stone Town of Zanzibar and Mozambique Island, is projected to more than triple by 2050 under a moderate emissions scenario.

Impacts are cumulative and some will persist for centuries after the world achieves net-zero emissions. Climate change is a threat multiplier, exacerbating existing threats, impacting sites in increasingly complex ways, and demanding further resources for management and adaptation. Food insecurity, social stresses and the displacement of populations as a consequence of climate change will further increase pressures on World Heritage sites.

The concept of outstanding universal value is fundamental to the World Heritage Convention and its processes. OUV has generally been interpreted assuming that the environment is largely stationary, something that climate change has proved incorrect. It will ultimately be impossible to maintain the outstanding universal value for which many sites were inscribed, even if effective global and local mitigation strategies and local adaptation strategies are implemented.

In Venice, the effectiveness of massive retractable barriers constructed at the entrance to the lagoon will be tested by the projected sea-level rise of anywhere from 17cm to 120cm by 2100 that will bring increasingly frequent, longer-lasting and potentially permanent flooding. A restoration and adaptation program is attempting to develop a suite of safe, acceptable interventions to help the Great Barrier Reef resist, adapt to, and recover from the impacts of climate change. However, it will be challenging to operationalise interventions at scale across this large World Heritage Area.

Substantive reforms are necessary for the World Heritage system to address these challenges. Although amending international conventions is notoriously difficult, the convention is a treaty where many important matters are dealt with in subsidiary documents, especially its operational guidelines, which are much easier to change than the convention, if state parties so wish.

An open-ended working group is working to finalise a policy document on climate action for World Heritage and to develop an implementation plan. The document outlines high-level directives but says little about the operational reforms required to address the scale and complexity of the challenges. Meaningful operational reforms are likely to be highly contested because of the differing priorities of various states parties. For example, African nations are very concerned about the under-representation of African sites on the World Heritage List and the perceived over-representation of African sites on the list of World Heritage in Danger.

In 2021, the Australian Academy of Science bought together 18 experts – in climate science, climate vulnerability assessment, IPCC processes, cultural, natural and Indigenous heritage, outlook reporting, site management, World Heritage system processes, environmental law, international law and diplomacy – in a roundtable on reforms to the convention to address the consequences of climate change. Their ideas for change focused on three key areas:

identification of climate-related threats to World Heritage sites;

the processes for state party reporting to the World Heritage Committee;

responses to climate impacts to outstanding universal value.

Identification of climate-related threats

Introducing a requirement for World Heritage nominations to include a standardised vulnerability assessment could provide a baseline against which climate-related impacts to its potential OUV could be monitored. Currently there is no agreed standard: several methods have been applied to individual sites and a thematic approach has also been used, assessing comparable sites or groups of sites facing similar risks. Clear guidelines around the requirements for such assessments need to be discussed and developed so that assessments are systematic, useful and comparable.

The World Heritage Committee responds to threats to outstanding universal value through complex and resource-hungry reporting processes – these include state-of-conservation reporting, reactive monitoring and a six-year cycle of periodic reporting based on geography. These processes are already under strain due to the large number of sites in the reporting cycle. In 2021, less than 20% of the state-of conservation reports were discussed by the committee. Given the anticipated increase in the number and severity of threats as a result of climate change, the reporting processes need reconsideration. Such change cannot take place without considerable discussion.

Responding to climate impacts

As climate change accelerates, the outstanding universal value of some World Heritage sites will be severely or permanently impacted. In others, the changes may be milder. Limits of acceptable change could be developed for each property to identify the amount or nature of change that each property’s attributes can sustain without irretrievable loss of OUV. Accepting that change is inevitable, improved methods are needed to assess significant and minor changes to each site’s statement of OUV as well as clearer guidelines and thresholds for including a site on the List of World Heritage in Danger or delisting it.

These reforms could result in more systematic and comparable evidence for climate impacts as a basis for realistic adaptation strategies and greater transparency and objectivity in decision-making by the World Heritage Committee.

Substantive reform of the operational guidelines would be a fitting project to commence in 2022, the 50th anniversary of the convention. We hope this article will stimulate widespread discussion about these matters, which are existential to the future of the Convention and its capacity to protect the world’s most precious heritage places in the face of climate change.

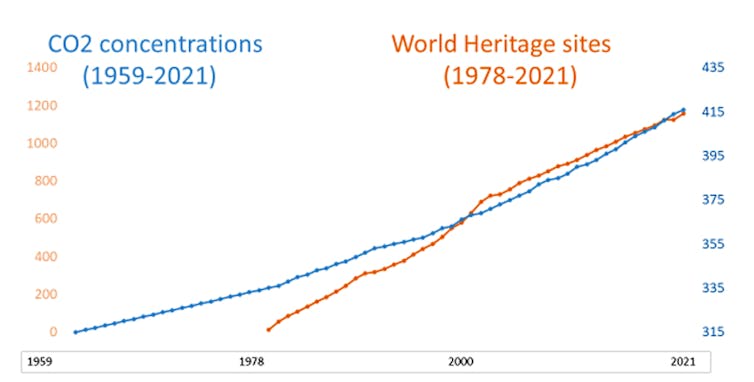

The authors gratefully acknowledge Greg Terrill for his ideas and comments and for Figure 1.

Les auteurs ne travaillent pas, ne conseillent pas, ne possèdent pas de parts, ne reçoivent pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'ont déclaré aucune autre affiliation que leur organisme de recherche.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.