It’s well established that the climate crisis and air pollution — two linked environmental and public health crises — are bad for our health. A UN report released earlier this year in sobering detail how the climate crisis threatens “human well-being.” But according to the New England Journal of Medicine, there’s one highly vulnerable group whose health is most at risk.

Yes, that’s right: we’re talking about children. Health professionals need to do more to protect them from the downstream effects of global warming and air pollution, the research shows.

On Wednesday, the New England Journal of Medicine released a set of articles as part of a new monthly series entitled “Fossil-Fuel Pollution and Climate Change.” The primary review article in this series examines an enormous amount of research to unpack just how much climate change and air pollution are harming children. The research also argues what medical practitioners can do about these joint health risks, which are “large and growing,” according to the report.

“The article summarizes a large body of data on the effects of air pollution and climate change—both driven by fossil fuel—on children’s health,” Frederica Perera, lead author of the review article and founding director of the Columbia Center for Children's Environmental Health, tells Inverse.

What’s new — The review article looks into the existing scientific literature to analyze the many ways climate change and air pollution impact children’s health.

Here are some of the key findings.

Climate change has a profound impact on mental health

“Of particular concern are the cumulative effects of air pollution and climate change on mental health,” write the authors.

Exposure to natural disasters — which are becoming more frequent as a result of a changing climate — in early childhood raises not just the “short-term risk of mental disorders but also confer a lasting vulnerability to anxiety, depression, and mood disorders in adulthood,” the report states.

Even indirect exposure to air pollution and climate change-linked disasters — through the news, for example — can lead to stress and other mental health concerns. The article cites surveys finding that nearly 60 percent of young people are “worried” or “extremely worried” about climate change.

For her part, Perera is concerned about “mental health effects in children that have been linked to both of these threats from fossil fuel.”

Air pollution exposure harms children’s development

The authors state that burning fossil fuels has created a “parallel crisis” of air pollution due to the release of tiny airborne polluting particles known as PM2.5.

“The fetus, infant, and child are especially vulnerable to exposure to air pollution and climate change, which are already taking a major toll on the physical and mental health of children,” write the study authors.

According to the review, air pollution exposure — both during development in the womb and after birth — raises the risk of medical issues for children. Some of these potential concerns include:

- Preterm birth and low birth weights

- Increased asthma issues

- Intellectual disabilities

- Cognitive/attention disorders like attention deficit–hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Mental health concerns like depression

In London, children who were exposed to higher levels of air pollution were more likely to develop a major depressive disorder when they entered adulthood.

Climate change compounds air pollution risk

“Concurrent exposure to climate hazards and unsafe air quality is common,” write the study authors.

According to the report, at least 850 million children — roughly 1 in 3 worldwide — suffer from four or more climate hazards like severe drought, flooding, air pollution, and water scarcity. As the number of environmental risks increases, children are more likely to face numerous health issues that compound each other.

Children in the U.S are in danger, too

The study makes clear that it’s not just children in countries abroad that face the health threats of the climate crisis and air pollution.

But specific groups of children are especially at risk of climate change and air pollution-related issues. What concerned Perera most from her findings was the “recent data showing that children in communities of color and low-income communities are most exposed and most vulnerable to toxic effects of air pollution and impacts of climate change.”

For example, in a world with 2 degrees Celsius global warming, Black children are one-third more likely to live in areas with high asthma diagnoses — often due to nearby sites of air pollution like oil fields or factories — than white children. Low-income communities of color are more likely to live in areas exposed to higher concentrations of heat — known as the urban heat island effect — due to fewer trees providing shade and dense housing and highways. These historically disadvantaged communities also face more adverse outcomes from extreme storms such as Hurricane Harvey.

“Protection of children’s health requires that health professionals understand the multiple harms to children from climate change and air pollution and use available strategies to reduce these harms,” concluded the authors.

Why it matters — Children are often not in a position to advocate for themselves, which means they are typically left out of public health discussions on the climate crisis.

Perera says that “children are especially vulnerable” to the impacts of a changing climate and air pollution on their still-developing bodies, particularly as a result of their immature biological defense, greater food and fluid requirements than adults, and difficulty regulating body temperature in extreme heat.

Therefore, it’s crucial for medical professionals to provide targeted health assessments and care that consider how climate change and air pollution impact their patients.

In no uncertain terms, the authors argue:

Health professionals have the power to protect the children they care for by screening to identify those at high risk for associated health consequences; by educating them, their families, and others more broadly about these risks and effective interventions; and by advocating for strong mitigation and adaptation strategies.

The article mentions some resources available to medical professionals, such as the American Board of Pediatrics’ Maintenance of Certification module on climate, health, and equity. Some medical schools are also beginning to incorporate climate change into their curriculum.

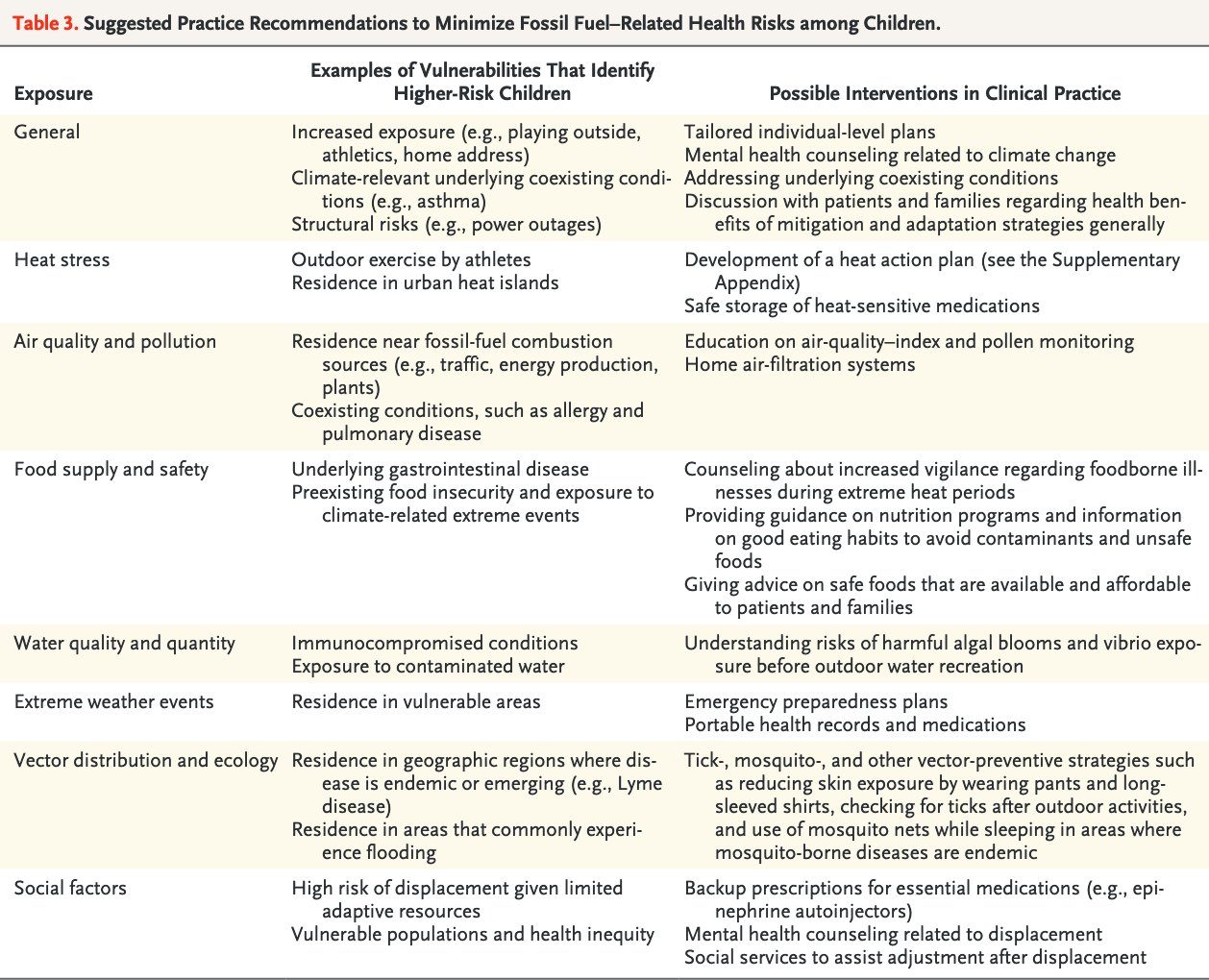

Table 3 of the article offers specific ways that medical professionals can offer care to patients, including screenings of populations who are more likely to be at risk of air pollution and climate change-related issues based on their background and activity level, as well as appropriate behavioral modification and climate adaptation strategies to reduce harm to children.

For example, children who participate in athletic activities could benefit from tailored plans to protect them from extreme heat, whereas families with children — especially those with asthma — who live near polluting facilities may need to monitor pollen levels and the air quality index before going outdoors.

“Suggested behavioral changes need to take into account the socioeconomic status of children so that the changes are actionable and durable and empower the child and family rather than making them feel powerless, afraid, or guilty,” conclude the authors.

What’s next — While the review article provides a comprehensive overview of what we know so far about climate change and children’s health, it also says we need far more information to help this vulnerable age group.

The article states: “It is of paramount importance that research findings be rapidly translated into policies to protect and improve children’s and maternal health, with special focus on vulnerable populations.”

But ultimately, we need government action — in addition to environmental-specific healthcare and research — to truly protect children from climate change and air pollution. The first strategy the paper outlines — adaptation to climate change — can only go so far without tackling the source of the problem: greenhouse gases, which are largely driven by fossil fuel production.

As part of their second strategy, the authors argue that federal and state policies shifting away from fossil fuels to renewable energy to reduce greenhouse gases and global warming will help safeguard children’s well-being.

“Governmental policies that have directly targeted emissions from fossil-fuel burning can both benefit children’s health and be cost-saving,” conclude the authors.