At last year’s US Africa leaders summit in Washington the US signed an historic memorandum of understanding with Zambia and the Democratic Republic of Congo to develop an electric vehicle battery supply chain.

At the summit, Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema also announced that Kobold metals, an exploration firm backed by billionaires Bill Gates, Jeff Bezos and Richard Branson, will invest US$150 million to develop a new mine in Zambia.

Zambia is particularly well positioned to supply what the world needs. It has substantial reserves of copper and cobalt, critical metals for the transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy. Due to their broad uses in wind and solar powered technology and electric vehicle production, these metals will play a crucial role in a low carbon future.

Copper demand is expected to increase up to threefold by 2040 while cobalt demand is expected to rise over 20 fold.

Zambia has 6% of the world’s copper reserves, and the metal accounts for up to 80% of its export earnings.

The coming copper boom presents Zambia with an extraordinary opportunity – to enable mining profits as well as to power inclusive growth.

But, as Zambia’s history shows, this is easier said than done. Successive rises in copper prices have not translated into reducing poverty or inequality. Zambia is still the fourth most unequal country in the world.

Based on our published research and expertise – including work with the International Growth Centre in the London School of Economics and engagement with the Zambian government on a research agenda for the country’s mining sector – we argue that Zambia can benefit from the energy transition underway. But it can only do so by harnessing the non-tax benefits of mining.

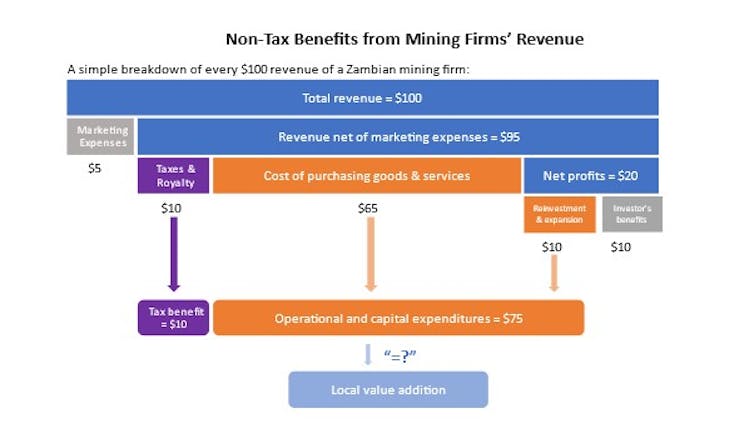

Non-tax benefits are the opportunities that stem from the mining activity itself. Most mining firms spend the bulk of their revenue on operational and capital expenditures, a larger share than goes towards either profits or government tax.

A non-tax benefit approach would mean that Zambian companies and workers would participate in mining’s value chain, and Zambian communities would benefit from the infrastructure needed to extract and move the bulk materials.

In the past, Zambia has been more focused on capturing tax benefits through changes to the fiscal regime. But a balanced approach of a stable mining taxation policy and the pursuit of non-tax benefits could deliver broader gains.

Zambia’s unequal growth story

Zambia’s track record for converting commodity booms into tangible benefits is mixed at best.

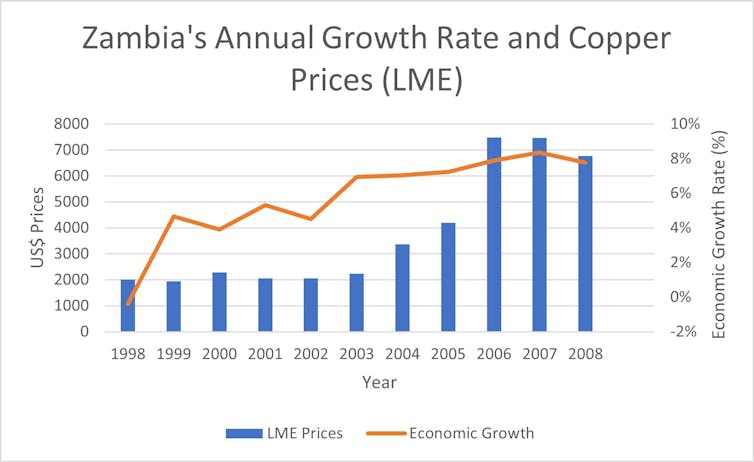

Take the last commodity cycle. Sparked by growing demand from China, copper prices began to increase in 2004. From 2003 to 2006 the price of copper, Zambia’s main export, more than tripled. Zambia’s economic growth rate took off in response. (See Figure 1.)

Yet there was no corresponding impact on poverty and income inequality. Zambia’s Gini coefficient, a measure of inequality, actually rose slightly during the cycle.

Even Zambia’s poverty rate, as measured by the percentage of the population living on less than US$2.15 per day (in 2017 purchasing power parity dollars), rose through 2010 before starting to reverse.

That year, a stunning 68.5% of Zambia’s people were living in poverty in a country where annual GDP per person was a much more impressive US$3,125.52 (also in 2017 dollars) – four times the poverty rate.

During commodity booms, governments may be tempted to focus on capturing short-term gains, which are frequently understood in monetary terms and primarily as tax benefits.

For Zambia, this dynamic was overlaid on top of the disastrous advice the government had received on how to reopen its previously nationalised copper sector a decade earlier.

The Zambian government entered into unfavourable terms with new mine owners, offering generous tax incentives that led to a loss in tax revenue just a handful of years before the copper price rose.

This fuelled a fixation on getting tax revenue from the sector.

In 2008, amid the boom, Zambia introduced a windfall tax on mining profits in an attempt to capture more benefits from the sector. Less emphasis was placed on the largely untapped non-tax benefits.

Why non-tax benefits?

Non-tax benefits are where the real potential to drive inclusive growth lies, as we detail below.

Figure two is a hypothetical one that illustrates the point. For every $100 generated in revenue, imagine that $70 is spent on operational and capital expenditures, that is, running the mine and expanding operations. (This is not unrealistic: margins in the sector are not very high most of the time.)

If more of this were spent within the country rather than being sent abroad to import the majority of goods and services, it could contribute to business opportunities for Zambian companies and high-paying jobs for Zambian workers.

In 2012, the costs of goods and services consumed “upstream” by the Zambian mining sector was valued at US$2.5 billion annually. Spending more of that domestically would have a much wider impact. It would create income and jobs directly. And that income would finance further consumption and investment through the local economy.

Non-tax benefits can also emerge from “sidestream” projects related to mining expenditure, adding value to the wider economy. The power, rail and road projects that enable mining activity can provide the backbone to make other economic activities competitive.

“Downstream” linkages are also possible – delivering the mining firm’s output to other firms that process it into intermediate goods and final products.

What would non-tax benefits look like for Zambia?

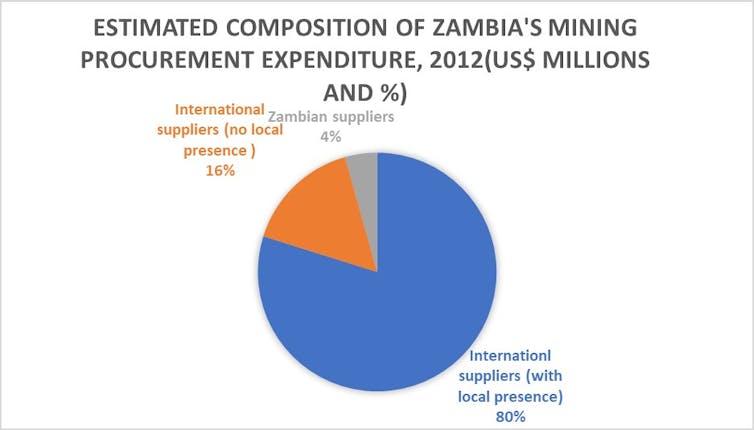

Figure three shows the breakdown of Zambian mining firms’ goods and services expenditure.

In 2012, 96% of all service were provided by foreign firms. Only 4% were provided by Zambian-owned firms. These were mostly supplying non-core goods and services such as catering, security and office maintenance.

Capturing more of mining’s upstream value chain in Zambia represents a major growth opportunity.

One way to make this happen is through a local content strategy that would give a greater role to Zambian suppliers and workers in the mining sector.

Another growth opportunity is the side-stream linkages with the electricity generation sector. For example, a mining company could sell surplus renewable power to the grid.

Zambia shouldn’t ignore mining taxation

By advocating for non-tax benefits, we are not suggesting that taxation be ignored. Copper reserves over time will run out, or copper will be rendered obsolete by some new technology. This is the risk with all natural resources. A government must generate tax revenue from its mineral resources while it can.

Multinational companies can find ways to pay as little tax as legally possible. In the past, Zambia tried to stop this by tinkering repeatedly with the mining tax system – without getting results.

Better would be to leave the tax regime in place and instead focus on monitoring and collection.

A governance dividend

Zambia’s government must keep in mind that poor governance will be a constraint to achieving any future – tax or non-tax – benefits.

This was the case during Zambia’s last boom. But the country is currently reaping a governance dividend with a new investor-friendly president, restored donor confidence and a recently secured IMF deal.

The conditions are in place for Zambia to use this boom to generate inclusive development.

The authors do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.