Earthworks are starting for a pilot plant near Tairawhiti which will turn waste heat into electricity via an up-to-5km-high whirling plume of water vapour. Science startup Vortex Power Systems is just one of a number of ‘clean tech’ companies in New Zealand starting to attract international attention

Today it’s a bog-standard paddock about 15km north of Tairawhiti (Gisborne). But in six months the field will be the home of an audacious pilot project investigating the potential for an artificially made waterspout (a spiralling tornado-like cloud of mist and air you might naturally see over the tropical ocean waters around Florida, for example) to take low grade industrial waste heat and turn it into electricity.

If it works – and a scale model has been trialled successfully over the past couple of years out of a postgrad engineering lab at the University of Auckland – there’s the potential for Vortex Power Systems' technology to be bolted onto a steel mill in China, a cement plant in the US, or a chemical factory in India, producing cost-effective electricity from the vast quantities of low-grade waste heat that now mostly billows uselessly out into the atmosphere via cooling towers.

READ MORE: * NZ deep tech VC fund opens capital raise for small investors * Polarising carbon capture tech back on NZ radar

About a half of the world’s total energy consumption is lost as waste heat, says Vortex CEO Perzaan Mehta. Of that, 63 percent is low grade waste heat – energy it’s hard to deal with at the moment.

“I believe we are one of the few or only solutions which will be able to address that low grade heat in an economically sensible way,” Mehta says.

Project that out to its hyperbolic extreme and “roughly 30 percent of all the world's power is what we should be targeting as our market”.

And in dollar terms? “The full total addressable market of this technology is hundreds of billions.”

There’s a long, long way to go before Vortex accesses any of that. Construction – including an Olympic-sized pool to hold the water to create the heat, and sail-like structures to direct the heat into a circular flow – will take six months, then the company needs up to a year to test the technology in all weathers.

The company raised $2 million in 2021, and is in the middle of a $5m capital raise, with the $3.5m already raised enough to get the plant built. But there will be more investment capital – potentially significantly more – needed to take Vortex beyond the pilot phase, and then the company will have to find international partners to build commercial-scale Vortex plants overseas.

And of course there’s the not insubstantial problem of persuading regulatory authorities in their major target markets – China, the US and India – that it’s safe to have 5km-high, electricity-producing waterspouts over their country.

As well as getting resource management approval for the pilot outside Tairawhiti, Vortex had to get permission from the Civil Aviation Authority.

For that reason, the first commercial plants sold overseas are likely to be in the countryside, not in big cities, Mehta says.

“I don’t suspect it’ll be in the middle of Shanghai – at least not initially. When you look at the geography, and we’ve done the scoping exercise, most of the plants producing a vast amount of waste heat – steel, chemical production, power plants – are in more remote locations.”

Global deep tech boom

Vortex is a tiny part of a growing international research and company landscape known as ‘deep tech’. At its simplest, deep tech involves businesses which find solutions to problems based on grunty scientific research or engineering work. It’s about physical stuff, not software.

Rocket Lab is probably our best-known deep tech company; another one is LanzaTech, whose technology feeds pollution to carbon-hungry microbes and turns it into fuels and chemicals. Both companies were founded in New Zealand but are now based largely in the US.

LanzaTech – and Vortex – are part of a subset of deep tech, known as ‘clean tech’ or sometimes ‘climate tech’.

Success in deep tech is hard. Developing the technology mostly takes years of research, often starting out in a university lab. It needs millions of dollars of capital investment before commercialisation, and there’s a big risk of failure.

Truly a bargain.

But with big problems comes the need for big solutions, particularly around climate change, says Mike Lim, a partner at Singapore-based clean tech investment company Trirec. Clean tech is increasingly popular with global investors, he says.

And somewhat unexpectedly, New Zealand has a stake in the game.

When the 'APAC [Asia Pacific] Cleantech 25' – an annual list of “private sustainable innovation companies that have gained the attention of market experts” – was announced in May, New Zealand had three startups on the list – Vortex Power Systems, sustainable ammonia production company Liquium, and Vertus Energy, which produces biofuels from waste.

That’s more than Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan or South Korea, and only a couple fewer than Australia, China, Singapore and India.

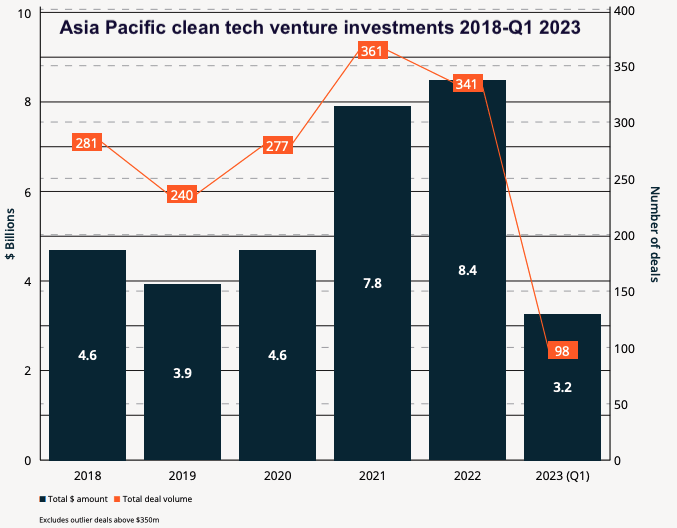

Cleantech 25 report author Anthony DeOrsey says venture and growth investments in clean tech companies in the Asia Pacific region for the first three months of 2023 were higher than the entire second half of 2022. In a single quarter, companies raised 30 percent of what they’d got in the whole previous year.

And the market is particularly buoyant in this part of the world. Companies in North America and Europe/Israel raised only 14 percent and 17 percent of their 2022 totals, respectively, in the first quarter of 2023.

Mike Lim first met some of this country’s deep tech companies when they were part of the Cleantech Forum Asia in Singapore last year.

“We were surprised by the quality of the startups we were seeing in terms of the technology they're working on, and the progress that they've made. So we decided we should make a trip down to New Zealand to check on what's going on.”

Lim spoke with Newsroom from Singapore after his tour, where he visited 15-20 deep tech companies, and signed a memorandum of understanding with local deep tech investment company Pacific Channel, an investor in Vortex Power Systems.

“We were blown away in the sense that New Zealand has a lot more to offer than we initially thought in terms of deep tech. We found very established research in the area of space, and strong know-how in materials science, which is very critical when it comes to the climate.”

Lim and his team also found research that was very application-focused (as opposed to purely academically driven), and founders getting good results on tight budgets.

“The capital efficiency of startups in New Zealand is just mind-boggling. They don't raise a lot, but they use the money so efficiently that they have achieved a lot more than what we've seen elsewhere. And that's a strength, especially in the current environment, which has been strained.”

Lim is talking about the venture capital markets, which have tightened, along with world economies, over the past few months.

And there are other challenges for Kiwi deep tech companies, he says. Distance from potential customers and investors, for example, a small local market, and being at the end of the supply chain.

“I heard the story of one startup where it took a few months to bring over some of the technical equipment they needed to test their technology. And even when they managed to get the equipment, there was more delay in terms of getting the right expertise to help them do the calibration.”

Would that put international investors off?

Not necessarily, Lim says. “New Zealand has been a hidden gem until now,” he says. “But investors are looking for technology right now, or startups right now that can make real impact in terms of the climate change agenda.”

Ammonia for ships

Wellington-based clean ammonium production start-up Liquium is not just one of the APAC 25 companies, but Liquium founder director and Victoria University of Wellington Associate Professor of physics Franck Natali was also one of the inaugural recipients of the Bill Gates-funded Breakthrough Energy Fellowships in 2021.

Natali was the only recipient in the southern hemisphere.

The fellowships provide $500,000-$1.5m of non-dilutive investment (funding that does not require the recipient to give up equity in their company) for innovators working on technologies intended to help get the world to net zero carbon by 2050.

Liquium also raised $1.5m in seed funding in 2022 from local venture capitalists led by science and deep tech specialist Matū and supported by the Climate VC Fund, Stephen Tindall’s K1W1, and AngelHQ.

Chief executive Paul Geraghty says there’s “a lot of money sloshing around” overseas looking to fund clean tech companies, although the risk appetite has slowed somewhat this year.

“There’s a real drive for people divesting their funds from the traditional ROI [return on investment] promises and moving into companies which have more of an impact; companies which might save the world.”

New Zealand’s number 8 wire ethos – ingenuity, practicality and resourcefulness – is part of the scientific community, Geraghty says, and that’s brought our companies to the attention of overseas investors.

“Deep tech startups in New Zealand are demonstrating we can do quite a lot with relatively limited resources, and that we are using innovative thinking to solve problems.”

Ammonia, a toxic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen (NH3) which give cleaning products their distinctive pungent smell, is used to make fertiliser, and is attracting attention worldwide as one of the most promising alternative fuels for a shipping industry looking for a way to decarbonise.

Ammonia can be burned without producing CO2, is easier to store than hydrogen and costs less than fuel cells.

The trouble is, making ammonia using traditional methods uses a lot of fossil fuels and produces high emissions – up to 2 percent of the world’s total greenhouse gases come from ammonia production, according to some estimates.

Liquium scientists have developed new catalysts which make ammonia production greener, more energy efficient and – relative to alternative green sources – cheaper, Geraghty says.

But so far, the company has only done this at small scale. Over the next two to four years it needs to demonstrate it can produce 100kg of ammonia a day from its plants – and then more. And that it can do that consistently, safely and cleanly, whether the final product is used for fertiliser, marine fuel or even dry-year electricity back-up.

Unlike other deep tech companies launched in New Zealand, which found themselves moving overseas to be closer to funding and markets, Geraghty sees Liquium being able to remain here for a while longer.

NZ’s plentiful renewable energy means Liquium can turn green hydrogen into ammonium and then export that energy overseas.

“The first ammonia-fuelled vessel is going to come out this year or next year. And they are expecting half of all ships will run off ammonia in 30 years.

“This is, in my opinion, is one of the most exciting time to be alive in human history, because we are seeing the decarbonisation of our carbon world." – Paul Geraghty, CEO Liquium

“Ideally, we will make it cheaper, cleaner and more efficiently than anyone else.”

But like Vortex Power Systems, Liquium is near the beginning of a long road. This sort of science-based clean technology takes millions of dollars and many years to develop. LanzaTech took more than a decade to get its product to commercialisation stage, and Geraghty can imagine a similar trajectory for Liquium.

He tries not to talk pie-in-the-sky market numbers, but pushed, says green ammonia could potentially one day be a trillion dollar market; ammonia is already worth hundreds of billions.

“This is, in my opinion, is one of the most exciting time to be alive in human history, because we are seeing the decarbonisation of our carbon world. And within 30 years we have to turn the carbon tap off and turn the clean energy, clean fuel tap on.”

Emerald Scofield is excited too, but from the investor side. She has been involved in deep tech for four years, as senior associate at Pacific Channel, the early-stage investment company that signed the MOU with Mike Lim.

Scofield says Kiwi early stage companies have benefited from a rush of venture capital – mostly local, but some international too –over the past two or three years, when investors have been falling over themselves to find startups in the clean tech space.

Capital markets have tightened in the past 6-12 months, she says, and risk appetites have changed. That will mean more competition for funding, and some startups potentially not getting the capital they need to go to the next stage.

But the relative largesse of the past few years along with the appetite for clean tech solutions, has seen a big increase in Kiwi startups coming through and moving closer to commercialisation.

“There are just so many good companies coming through. If I had to put a number on it I might say our team has seen 40 [proposals] over the last couple of months,” Scofield says.

“In terms of ones we might seriously consider, there are probably 10-15 and we are in the process of whittling them down to one or two investments this year. And that’s proving really hard.”

Pacific Channel has $55m to invest in the fund and so far has deployed 60 percent of it. It will hand out approximately $10m-$15m over this year.

It’s one of the larger deep tech funds in New Zealand, but far from the only one.

“There’s definitely a lot more money around and I’m getting the sense with other funds at the moment that they are the busiest they have ever been, trying to review deals and prioritise.”

What are the challenges for Kiwi companies as they move from local investors and seed funding to pitching for international money for series A funding rounds and beyond?

Not thinking big enough, Scofield says.

“We see them valuing their market too conservatively. If you are trying to interest an investor, they are not going to get excited by a $5 million market, they are going to get excited about a billion-dollar market.

“One of our jobs is going ‘guys, you need to shift your mindset from ‘bootstrap’ to ‘accelerate’. And money is unfortunately the only way to get there.” – Emerald Scofield, Pacific Channel

“I mean, reaching a billion dollar market share within the next five years isn’t necessarily going to be obtainable, but if you are going out there with a small market size and you are competing for capital against much more ambitious companies, no one is going to be interested in you.

“It comes down to being ambitious and being vocal about it. Going overseas more and talking about the amazing things we are doing.”

Another challenge is getting founders to think bigger about the sums of money they are looking for, and to worry less about diluting their own shareholding.

“One of our jobs is going: ‘Guys, you need to shift your mindset from ‘bootstrap’ to ‘accelerate’. And money is unfortunately the only way to get there.'”

A third challenge is encouraging more collaboration – between companies and funds, and between researchers here and overseas. And encouraging people to be excited – not disappointed – when NZ companies move overseas to grow.

Mike Lim says Singapore has some of the same issues as New Zealand.

“Companies might start in Singapore, but we need to acknowledge that we don’t have the market for them to stay in Singapore – they have to go out. And we have to be proud.

“We have to produce them and have them out in the world conquering the world.”

Lim points to one of Trirec’s investments, lithium battery-recycling technology company Green Li-ion. Headquartered in Singapore, the company has Australian and Iranian founders, investors from Thailand, Korea, Norway and Portugal, a research base in Victoria, fabrication in Texas, and a base in Europe.

The science may be slow to develop, but Scofield says change in attitudes around clean tech are happening quickly.

“A couple of years ago, if you talked about ‘tech impact', people would just be like, yeah, it’s a nice story. But now, investors don't want to touch a company if it doesn’t have an ESG [environmental, social, governance] policy, or really think about impact.

“And deep tech is inherently impactful – you're solving a huge problem.

“You know, one of the things that strikes me about working in this space is I literally can change the world, right? How many people can actually say that?”