Fifty years ago this month, Aotearoa New Zealand established diplomatic relations with the People’s Republic of China. There are stories to be told about the relationship between China and Aotearoa, stories too often drowned out by diplomacy, geopolitics, and trade.

My own story begins a quarter of a century ago. I went to Wuhan University to study Mandarin, but my trip involved more than just language. If I made a list of memories, it would include the sea-sized Yangtze, a young man reciting a poem by heart in the twilight, and the earthy taste of lotus root.

Another thing on that list would be my first experience of being a racially marked minority. My experience wasn’t at all equivalent to the racism encountered by Māori and others here in Aotearoa. Whiteness continues to bring unfair privilege even when it is marked as other. Still, traveling to China brought home to me the racism of the place I had left behind.

I might, then, begin this story not in Wuhan in 1997 but in Aotearoa decades earlier with the recollection of a poem not in Chinese but English. I have in mind a poem by Hone Tuwhare, who rose to fame in the early 1960s, when he was acclaimed as the first Māori writer to publish a book of poetry in English.

Tuwhare’s friend and mentor R. A. K. Mason wrote a foreword to that first book, which was published by my maternal grandparents. As a Māori poet, Tuwhare was of course all too familiar with racism, white privilege, and colonisation. He writes about them in a mid-1970s poetic tribute to Mason:

Easy for you now, man. You’ve joined your literary ancestors, whilst I have problems still in finding mine, lost somewhere

in the confusing swirl, now thick now thin, Victoriana-Missionary fog hiding legalised land-rape and gentlemen thugs. Never mind, you’ve taught me

confidence and ease in dredging for my own bedraggled myths, and you bet: weighing the China experience yours and mine. They balance.

Tuwhare distinguishes between Mason’s white privilege and his own experience of ‘legalised land-rape,’ racism, and the loss of ancestors ‘in the confusing swirl’ of colonialism. He also affirms commonalities across the divide: their dislike of missionary zeal and the class privilege of ‘gentlemen thugs’—and surprisingly, their shared ‘China experience.’

Less surprising, though, when we consider that Mason spent the last three decades of his life engaged with China. The year after his death, Mason’s long-held dream of greater friendship between the two countries was realised with the establishment of diplomatic relations. The following year, Tuwhare visited China for the first time.

Tuwhare went to China as part of a ‘Maori Workers’ delegation’ that included Tame Iti, as a representative of Ngā Tamatoa, Miriama Rauhihi (later Rauhihi Ness) of the Polynesian Panthers and Ngā Tamatoa, and two trade unionists, Timi Te Maipi and Willie Wilson.

Hosted by the Chinese government, their tour took them to meet various non-Han communities with the goal of impressing on the visitors how much better China treated its diverse peoples.

From this perspective, the tour was a great success. In a published interview, Wilson explained: ‘Before I went to China I never had this hard-line attitude. I thought that this society was a bit racist but not totally . . . After being to China and seeing how the minorities are treated, how they are permitted to organise and run their own affairs, I was convinced . . . Minorities in China today enjoy a far more fortunate existence than Maoris [sic] in NZ.’

Wilson might not have learnt much about China, where Han chauvinism is just as pervasive and pernicious as Pākehā chauvinism, and where the Uyghur people today suffer its ugliest consequences. However, Wilson did learn something about Aotearoa. Again, it sometimes takes a trip to discover something about the place you left behind.

Tuwhare’s response to the trip was cannier. His poem ‘Song to a Herdsman’s Son’, written after a visit to Inner Mongolia, at first appears to be a piece of propaganda celebrating Chairman Mao’s ability to ‘Hurdle the Oceans’ and unite ‘the World’s People.’ But Tuwhare goes on to question such imperialist visions of transcending geographic and cultural difference. The poem ends instead with a distinctively Mongolian beverage: ‘salted tea with millet – a glass of hot milk’.

Tuwhare again tastes the difference between propaganda and reality in his poem ‘Soochow’. He cites Mao’s aphorism ‘revolution is not a dinner party’ only to subvert it through a description of his own supper: ‘But for dinner tonight, I will savour a slice or two of the lotus root, crisp and white.’

We are back again in ‘the confusing swirl’ – and in more ways than one. The turn to local cuisine once more undermines the propaganda, recalling Tuwhare’s similar struggle to find his own culture and ancestors amidst the confusing swirl of Pākehā colonialism. But it also leads Tuwhare home in another way.

In savouring the lotus root, Tuwhare becomes ‘A small child again / dribbling a haunted taste.’ The lotus root sends Tuwhare back in time, hurdling oceans, to that part of his childhood spent in the Chinese market gardens in Tāmaki Makaurau Auckland where his father worked and where he perhaps first experienced that now ‘haunted taste.’ The taste affirms connection across oceans and decades but is equally haunted by bitter memories of the racist attacks on Chinese market gardeners and the Māori who worked with them.

This essay too is haunted by travel, memory, and traumatic histories. At a twilight gathering at Wuhan University, I recall a local student reciting the poem 《一代人》 (‘A Generation’). Its author, Gu Cheng 顾城, was by then remembered not just as the poet who gave voice to a new individual sensibility after the Cultural Revolution but also as the poet who had murdered his wife on Waiheke Island before taking his own life.

I had a more personal memory of Gu Cheng as the eccentrically dressed ‘famous Chinese poet’ who came for dinner during my last year of primary school and talked intensely with my father (a poet of a homegrown and less famous kind). When I heard Gu Cheng’s words recited that evening at Wuhan University, I saw him again sitting at our kitchen table.

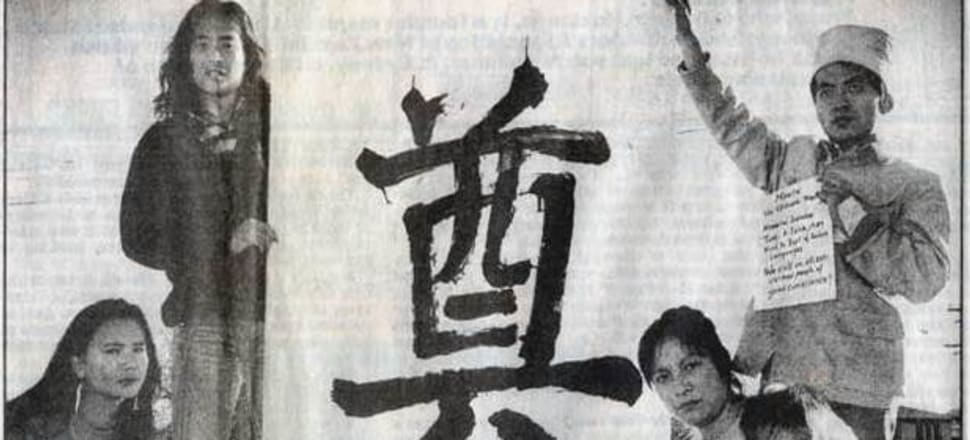

A few weeks ago, I watched a video of students gathering at the very same spot on the Wuhan campus. My mind filled with another childhood memory, another protest, and another Chinese poet: Yang Lian 杨炼 arriving at our home on the evening of June 4, 1989. As the television screened images of tanks and bloodied protesters, Yang Lian used our phone in a desperate effort to get through to friends and family in Beijing.

Tuwhare too visited our house in Tāmaki Makaurau during those years. Only in writing this essay have I realised that my childhood memories of the visits of these three poets intersect in what Tuwhare calls ‘the China experience.’

Sometimes you travel a long way only to discover something that was there all along in the place you thought you’d left behind.

* This article draws on an essay that appears in Encountering China: New Zealanders and the People’s Republic, just out from Massey University Press