Rev. James M. Lawson Jr., who died on June 9, 2024, at the age of 95, was a Methodist minister and a powerful advocate of nonviolence during the Civil Rights Movement.

Lawson is best known for piloting two crucial civil rights campaigns – one in Nashville in 1960 and the other in Memphis in 1968.

In Nashville, Lawson trained students in the systematic use of nonviolent pressure. Interracial teams of students would sit at local lunch counters reserved for white people to defy segregation laws. Most importantly, he prepared them to be beaten or arrested. Following the example of Mahatma Gandhi, who used nonviolent resistance to challenge the British occupation of India, students engaged in collective nonviolent direct action. When the first wave of students were beaten or arrested, another wave of students flowed in behind them to take their places.

Hundreds were arrested or beaten before their actions led Nashville Mayor Ben West to publicly declare segregation immoral – a signal to downtown business owners it was time to end the policy of racial segregation in Nashville.

In Memphis, Lawson organized what became the final campaign of Martin Luther King Jr.’s life. King came to Memphis to ally with 1,300 impoverished sanitation workers striking against their employer, the municipal government of Memphis, because of poor wages and work conditions. When two workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, were crushed by a trash compactor as they took shelter from the rain, the workers decided they’d had enough and went on strike. Ultimately, they won a small pay increase and modest workplace improvements.

By 1968, Lawson had established himself as the leading authority on nonviolent conflict, a fact to which King himself attested. I have studied Lawson for more than 20 years, and I argue that he was among the most important figures in the nonviolent civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.

Early influences

Lawson grew up in Massillon, Ohio. His father, James M. Lawson Sr., was an African Methodist Episcopal minister who carried a pistol on his hip, perhaps an odd influence for an advocate of nonviolence. But the elder Lawson taught his son to always fight for what’s right.

His mother taught him the power of love. After Lawson slapped a white child who had called him a racial slur, his mother patiently asked, “Jimmy, what good did that do … there must be a better way.” Lawson called this moment “a numinous experience, a transforming experience … that began my experiment with finding the better way.”

As a student at Baldwin Wallace College, he was inspired by Abraham Johannes Muste, whom Time magazine described as America’s “number one pacifist.” Muste represented the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the oldest pacifist group opposing war in U.S. history.

Lawson also closely followed the work of the Congress of Racial Equality as it challenged segregation laws with nonviolent direct action in the early 1940s.

Lawson began to see that he had an opportunity: He could challenge segregation, and he could use nonviolence to do it. Inspired by these examples, Lawson decided he would never again obey a racial segregation law. He said: “I made the commitment that … I’m not going to be disciplined, contorted into something that I’m not.”

Nonviolence and segregation laws

Lawson put his philosophy into practice when the United States entered into war with Korea in 1950. Required to register for the draft, Lawson concluded he would not cooperate: “There were certain laws that the Christian had to disobey: the laws of segregation and the laws of conscription. So then I sent back my draft cards and said I could no longer cooperate with it.”

He felt that conscription laws had the same fundamental problem as segregation laws. They, too, were “a complete denial of the meaning of freedom.”

For his refusal to fight in the Korean War, Lawson spent nearly 14 months in prison. After being paroled, he went to India, where he worked with the Student Christian Movement in Nagpur. Lawson sought to better understand Gandhian principles so he could apply them to battling Jim Crow segregation, racism and violence.

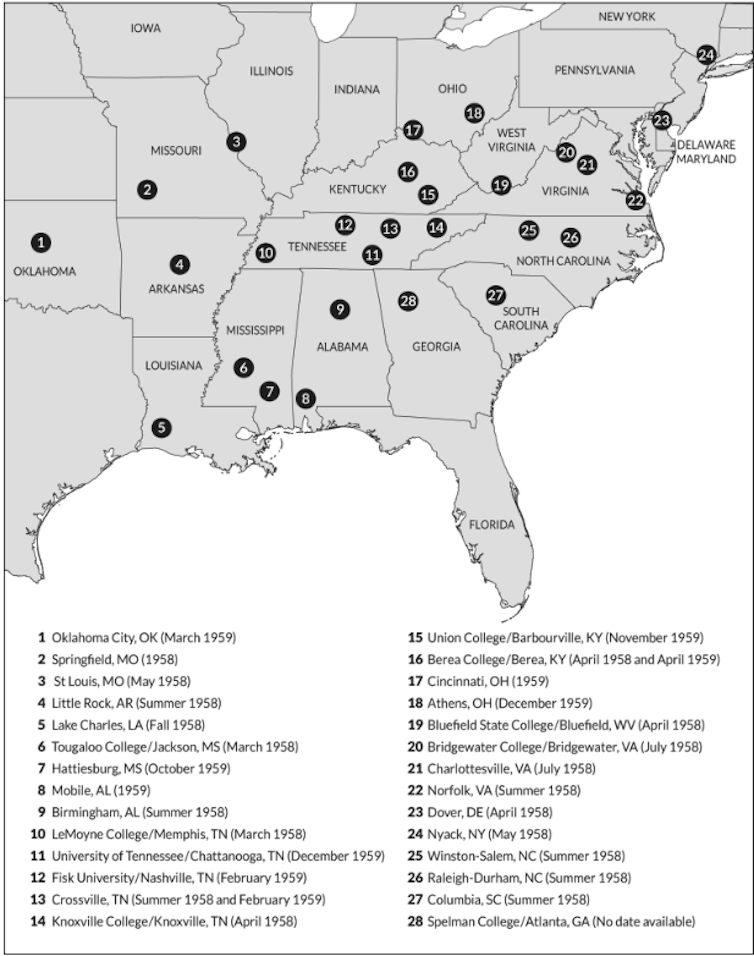

In the fall of 1957, Lawson made the decision to move south and became the southern secretary for the Fellowship of Reconciliation, a primarily white pacifist group long interested in the issue of African American civil rights. Lawson was based in Nashville, and in his first full year of work he traveled to every former Confederate state but Florida, teaching the philosophy and practice of nonviolent protest.

He taught Black Christian students that by resisting segregation, they were emulating Jesus, who challenged the oppression of the Roman Empire.

Lawson taught his students that Jim Crow laws were designed to make Black Americans both feel and act like second-class citizens. He argued it was unethical to abide by such laws. To knowingly cooperate with evil is to live a lie, Lawson argued. To participate in your own suffering and the suffering of others is a fate worse than death, he said.

His powerful argument convinced many Americans that they could no longer cooperate with Jim Crow. As his student Diane Nash recalled, “Oppression always requires the participation of the oppressed.”

Lawson and students across the nation used nonviolent noncooperation to end legalized racial segregation in the United States. He taught his students they must be willing to fight and die for the cause of human freedom and justice, but that they shall not kill.

Lawson’s influence lives on

Lawson carried forward his philosophy of nonviolence when he moved to California in 1974. He allied with the Justice for Janitors movement and continued teaching workshops on nonviolence up until his death.

Lawson leaves behind powerful teachings. In a recent documentary called “Love & Solidarity,” Lawson said: “Love is power. It is the most creative power in the universe. It is the greatest force that is available to humankind. Humankind needs to learn how to use it.”

In a world roiled by violence, Lawson has shown us that nonviolence can be an even more powerful force to create societies defined by justice, freedom and equity.

Anthony Siracusa does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.