In a time of national crisis, when human rights and democratic ideals are under threat, it’s everyone’s responsibility to take a stand—but those of us who benefit from the harmful systems fueling the emergency have an even greater moral obligation to act. For the Rev. Dr. Carter Heyward, a groundbreaking feminist theologian, that means Christians need to play a much bigger role in the fight against fascism.

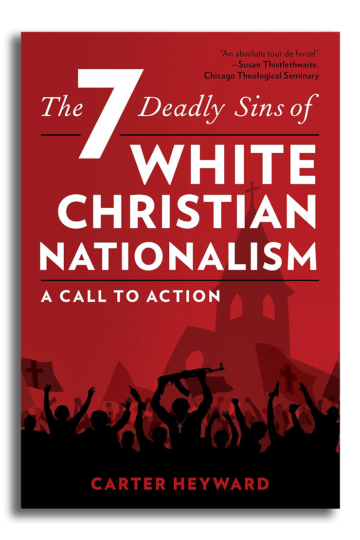

Today’s Republican Party seems intent on transforming the United States into a grimly theocratic nation, inspired by a deeply capitalistic form of Christianity. Though Trumpism offers a novel twist on old bigotries, its roots run deep in our country’s history. “Nothing we are witnessing in the 21st century is new,” Heyward writes in the introduction to her book, The Seven Deadly Sins of White Christian Nationalism: A Call to Action, released in September. “In the past several years, however, our problems have come to a boil.”

Heyward is an Episcopal priest, a lesbian, and a lifelong activist for social justice, granting her a unique perspective on the current emergency. In her book, she skillfully contextualizes our political moment, connecting it to our country’s history of colonization, the genocide of Native Americans, and the enslavement of Black people. In each case, religion, specifically Christianity, was used to justify inhumanity.

Heyward believes that these foundational crimes echo in the modern day through seven cultural sins including misogyny, white supremacy, and the capitalist capture of American spirituality. She also believes that Christians can be a force for liberation and positive change, and she outlines seven ways believers can take action. These include supporting the rights (and inherent sacredness) of Black people, women, and LGBTQ+ folks; seeking more sustainable ways of living on the Earth; and transforming capitalism into a newer, more equitable economic system.

Even non-Christians will benefit from Seven Deadly Sins’ cogent analysis of the rise of American theocracy, and Heyward is quick to point out ways even those who don’t practice Christianity benefit from systems like white privilege.

The Observer spoke with Heyward on the phone last month, just after the release of her book, about the dangers of Christian fascism, white nationalism, and the conversations she hopes to spark in American churches.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

One thing that jumped out at me while reading your book is a lot of times you’ll see, especially on social media, Christians acting very defensive when another Christian does something offensive. “That’s not who we are,” they’ll say. I appreciated your approach, which is a bit more nuanced and asks Christians to take responsibility.

Yes, I think that’s exactly right. My hope is that people in general, but Christians in particular, might take a look at this book and talk with each other about the issues it raises. My thesis is that all Christians are involved in the problem, not just right-wing Christians, not just left-wing Christians. I’m very progressive and that’s clear from page one. Fine with me. I’m also saying I hope you won’t dismiss it just because you’re more conservative than I am.

My big complaint about the liberal church I grew up in is that it’s been so silent on matters of social justice. I’ve known since I was a teenager, maybe since I was a child, that the teachings of Jesus to love thy neighbor really needed to apply to a lot of stuff in our society, beginning with questions about race relations. Why were the churches, the predominantly white churches, so quiet on that? And that would still be my question today: Why don’t liberal churches speak up? We can’t blame stuff on the conservative churches if we’re just going about our business. And together with our more conservative Christian brothers and sisters and siblings, we probably could find some ways, maybe not all the time on every issue, but on many issues we could find ways of giving and taking and compromising more than we do.

We have to hope that there’s people out there, you use Liz Cheney as an example in the book, people who are conservative but who still have their moral conscience active and are feeling the same fear, disquiet, concern about all the things that are happening.

We really, really do. And hope that they will come out of their closets, break their silence, do whatever they can to break out of the bondage that’s keeping them tied to the madness of—I don’t really think it began with Donald Trump, but it’s coming to the foreground with Trumpism. And he is really presenting himself as the savior of our nation. And that is so, so utterly untrue.

Trump is interesting because he doesn’t seem, at least when I try to put myself in the shoes of a conservative Christian, he doesn’t seem like a very religious or moral guy, but he is very tied into what you call capitalist Christianity.

My perception of Mr. Trump is that he for a long time would have identified, if he did at all politically, as a liberal Democrat, somebody who was pro-choice and pro-LGBTQ+, and certainly on social issues would have been very open-minded. I imagine he’s always been pretty conservative on fiscal issues, though I’m not even sure about that because I don’t know what he was like as a younger man, but certainly his father was not much of an ethical teacher when it came to how to handle finances. Donald, I think, grew up in a cult, a personal culture of greed. I mean, from what he says about his love of winning and his love of money, I mean, that’s hardly a Christian perception of what really matters. It used to be that right-wing and left-wing Christians could have agreed about that. You know, something matters to us more than money. Everybody needs enough money to live and have clothes and food. But we don’t need to simply have money that generates money. And I think that’s been Trump’s guiding light, that profit-at-all-cost ethic.

Here in Texas, we’ve seen growing attacks on LGBTQ+ rights. At the state level, we’ve got the government using Child Protective Services to investigate families with trans kids as child abusers. And then at the street level, during Pride Month this year, it was almost nightmarish in the Dallas area. Almost every day extremists were threatening a different drag show or Pride event. And the people organizing these attacks proudly identify as Christian nationalists or Christian fascists.

That is interesting that people are openly identifying, proudly, as Christian nationalists. I started writing this book in response to the January 6 [2021] atrocities. I didn’t have any idea when I was writing it how much more relevant it was going to be by the time it was published. And I think I say somewhere in there that I suppose there are Christians who are proudly Christian nationalists, especially the ones who really want to “own the libs.”

You do.

Christian nationalism, they see that as a positive because they really do believe that this should be a country ruled by white, straight, ostensibly straight at least, Christian men, to the exclusion of women, people of other faiths, traditions, any kind of queer people, immigrants, except maybe immigrants from white Northern European countries who look like them.

You know, we have been here before in our society and we’ve always managed to get through it and eventually get a little bit better and open up a little bit more. I’m hoping, hoping, hoping that we can do that now, despite them and some of the lunacy that goes on in Texas, or in my home state of North Carolina, or in any Republican state legislature.

“You know, we have been here before in our society and we’ve always managed to get through it and eventually get a little bit better and open up a little bit more. I’m hoping, hoping, hoping that we can do that now.”

One of the things that I appreciate the most in your book is that, even though the main audience is Christians, you emphasize that everyone in America is soaking this in. No one can escape from the structures of Christian nationalism. And as a white person, I’m benefitting from it regardless of my religious beliefs.

We’re all being poisoned by it. We’re all being shaped by it. We may be very deeply committed to justice, whether it’s gender justice, sexual justice, racial justice, all of the above, transforming capitalism into a more humane system, environmentalist, pacifist, whatever our passion is, we may be that, but we’re still being shaped by white Christian nationalism in ways that we just 99.9 percent of the time cannot see or grasp fully.

One of the things I’m hoping this book will help people do is not be defensive about it. We don’t need to apologize for being who we are. I’m a white woman who has benefited enormously from white entitlement and white power and white privilege throughout my life. And that doesn’t make me an evil person, but it does mean that I need to struggle against that structure of evil because it’s breaking us all apart. White people and everybody else. Same with gender issues. Here I am, a lesbian and a woman. And in both of those ways, in this society, I am part of an oppressed group of people. But I’m also a white, economically privileged lesbian woman.

I think that makes it hard for people to see how bad things have become at this moment. What are your thoughts on that, why aren’t people more alert to what’s happening?

That’s a really good question. I don’t think it’s simply that people are self-absorbed and selfish. But I think most of us have a hard time figuring out what we can do about anything. It can be so overwhelming that we don’t realize we have any power. And this is where the churches could help us so much, because as one individual woman sitting on a mountaintop in North Carolina, as I am right now, I don’t have a hell of a lot of power. I have plenty of money so that I’m not in need. I have never been in economic need in my life. And therefore, in a very personal way, I’m okay.

But if I want to try to make a difference, then I need to hook up with other people. And that’s where churches—and other organizations, but specifically in this book I’m talking about Christian churches—can help us make connections with each other whereby we become stronger, less powerless. We have different talents that we can put to use: Some of us can write books. Some of us can give sermons. Some of us can cook food in the food pantry. So some can do this. Some can do that. And we can all contact our legislators and put pressure on people both at the local levels and at the state and the national level. We can do things, and together we are stronger. And I think it’s that failure to see that we can get together that is our worst impediment right now. And that leaves people feeling isolated or playing computer games.

And therefore, we need to be able to speak with one another, do things together and become a mightier force because we are collective and not simply individuals.

We need to come together in strong communities.

That’s exactly right.