The Roman Catholic Church isn’t exactly renowned for its love of rock music, but a curious recent event suggests otherwise. In the summer of 2010, L’Osservatore Romano, the Vatican’s official newspaper, decided to publish a list of its Top 10 albums of all time. It was full of pretty obvious big-selling selections: Rumours, Thriller, Achtung Baby, Graceland, (What’s The Story) Morning Glory. But at the real business end of the list – tucked between Revolver at No.1 and The Dark Side Of The Moon in third spot – was If I Could Only Remember My Name, a relatively obscure offering from David Crosby.

Just how this album became the pope-pickers’ record of choice is something of a mystery. Released in February 1971, it was the product of weeks of weed-fugged recordings made by one of the era’s most Dionysian characters and his assorted chums, featuring songs about free love, getting high and driving by the local high school at hometime, just to watch the girls come out.

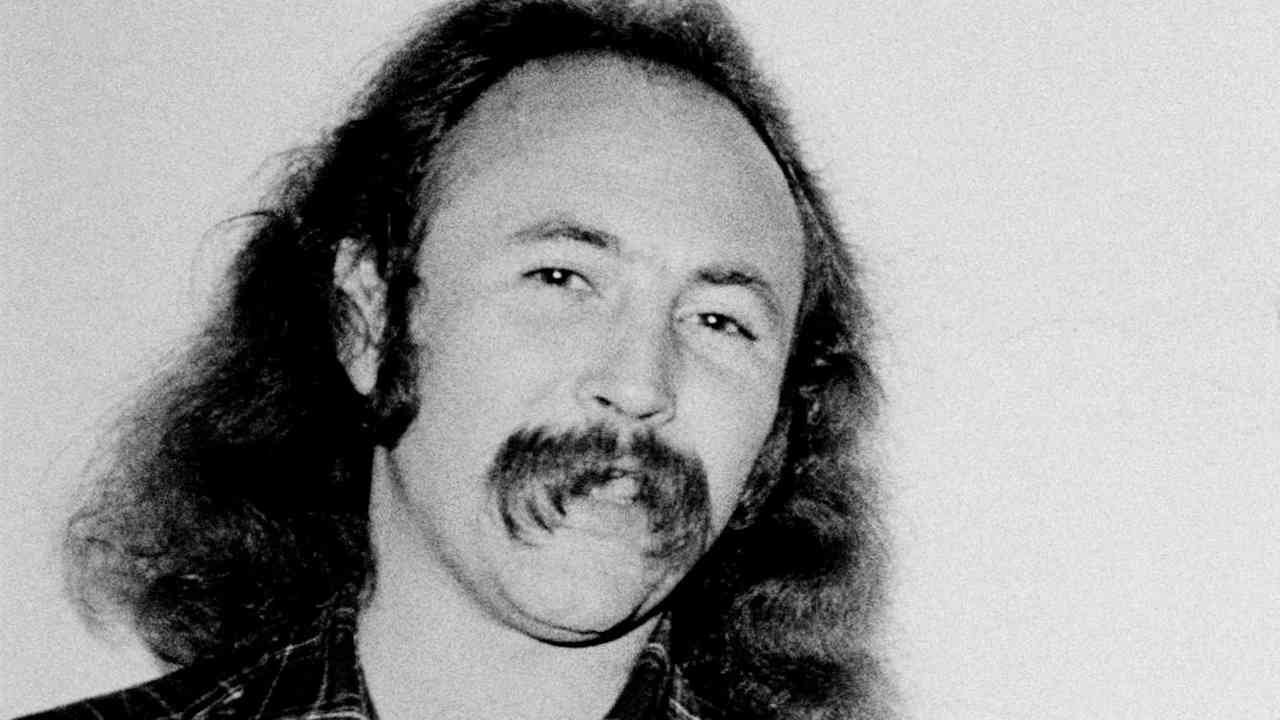

Crosby was a man fabled for his voracious appetites, be they drugs, sex or music. Even amid the legendarily open-minded counterculture of the 1960s, Crosby was pushing things to their limits, and very often beyond. His tastes were catholic alright, but with an emphatically small ‘c’.

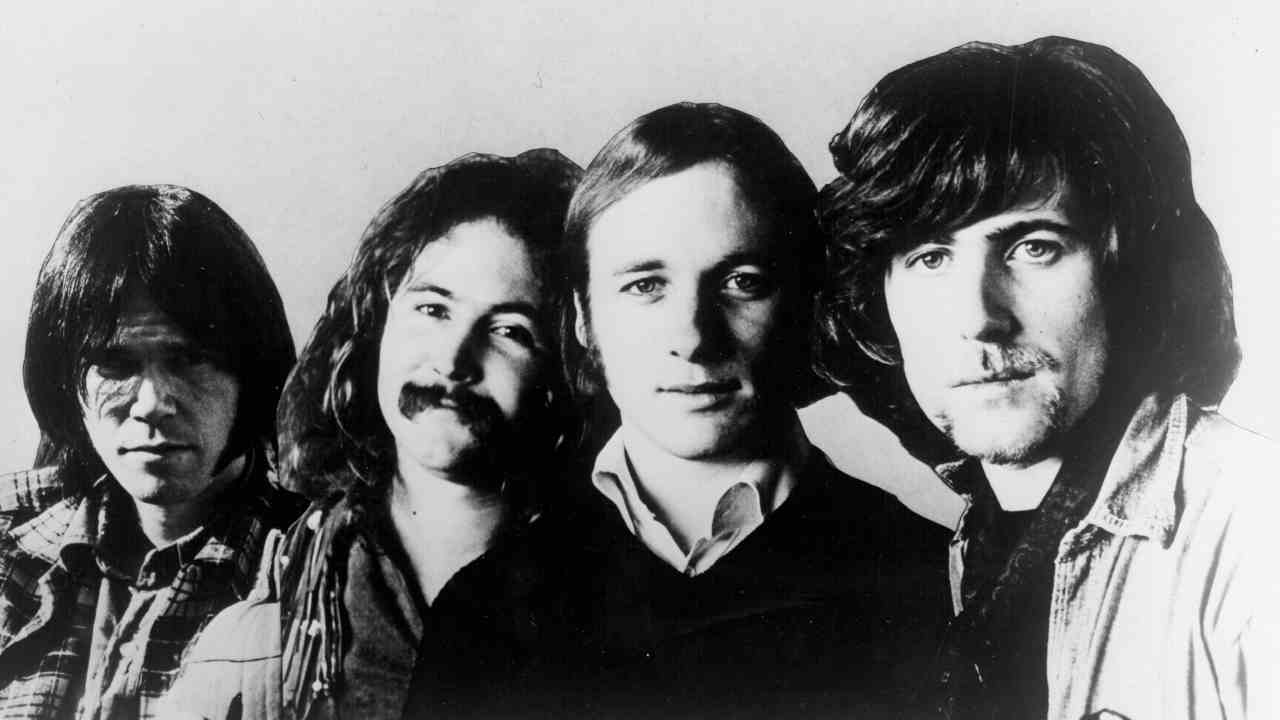

Crosby had first risen to fame with The Byrds, the Californian quintet who more or less invented folk-rock in the mid 60s with ringing versions of Dylan’s Mr Tambourine Man and Pete Seeger’s Turn! Turn! Turn!, before breaking through to a fifth dimension with the voyaging psychedelia of Eight Miles High. His penchant for causing trouble and irking his fellow bandmates led to him being booted out in 1968, after which Crosby’s ego found its natural place amid the similarly headstrong supergroup Crosby, Stills & Nash, who, with the arrival of Neil Young, soon morphed into CSNY.

But by July 1970 it had all gone sour. A couple of highly lucrative US tours had been blighted by in-fighting, petty jealousies and perceived slights. CSNY’s Déjà Vu, released earlier that year, had yielded some extraordinary music but at a heavy price. The sessions had been marked by escalating tensions within the group, heightened by the fact that all four of them were dealing with break-ups and estrangements in their personal lives. Drummer Dallas Taylor later likened the making of Déjà Vu to “a nightmare”, the whole thing lent further intensity by copious mounds of cocaine and a ready river of booze.

Crosby was actually hurting more than most, though his hedonistic lifestyle, on the surface at least, did much to deaden the pain. His lover Christine Hinton, who he’d first met during his time in The Byrds and the inspiration behind the classic Guinnevere, had died in a car crash in September 1969. Crosby was inconsolable; he took to the bottle and began using heroin. When it came time to make If I Could Only Remember My Name, in November 1970, he was living in his houseboat in Sausalito harbour and recording at all hours of the night at Wally Heider’s studio in San Francisco.

“It was a very tough time for me,” Crosby told Classic Rock in 2011, on the 40th anniversary of the album. “When we’d been recording Déjà Vu Christine had gotten killed and I was totally depressed. The studio was mainly somewhere I could go where I’d feel something other than just lost. It was the only place I got to stop crying.”

So was recording If I Could Only Remember My Name a healing experience?

“I wasn’t even trying to get healed, man,” Crosby replied. “I was just trying to make it through. But it was healing in the sense that, during Déjà Vu and throughout If I Could Only Remember My Name, I was still incredibly sad about Christine. And I didn’t really have any way to deal with that. It didn’t fix it, but the studio was the only place that worked for me in my life. Everything else was tinged with her death. It was very difficult. That feeling intruded into the studio sometimes too. At the Déjà Vu sessions, I remember just sitting on the floor and crying. By the time of If I Could Only Remember My Name, I was dealing with it, but not well. I was mostly just suppressing it. The studio and my boat in Sausalito were my only places of refuge.”

He wasn’t alone much, either. The sessions were peppered with big-name pals, among them Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, Graham Nash and the cream of the Bay Area rock fraternity: Jerry Garcia, Phil Lesh, Jack Casady, Jorma Kaukonen, Greg Rolie, Grace Slick and Paul Kantner.

“We recorded it all at night,” recalled Crosby. “Graham and Garcia were in the studio with me more or less every night. Both of them were there, over and over and over. Phil Lesh too, and the other guys from The Grateful Dead. People would just drop by – Neil, Grace, Joni, Paul Kantner. It was a very loose kind of thing. I’d play them a song, they’d get a feel for it, learn the changes and then take it from there.”

Engineer Stephen Barncard, who had manned the desks on Déjà Vu and had also co-produced the Grateful Dead’s American Beauty earlier that year, was Crosby’s preferred choice of studio hand. But he didn’t exactly leap at the chance. He’d already witnessed the mercurial, and sometimes volatile, Crosby at very close quarters.

“Crosby had to convince me to do his solo album,” Barncard admits. “I turned him down three times. And we’ve been friends ever since. I’ve seen all the phases of David now, but back then I was still scared of him and thought he was like a firecracker that could go off at any moment. So I wasn’t going to fuck that up for anything. I really prepped those sessions so it was perfect for when he walked in. But I never knew what he was going to do. And I don’t think he knew either.”

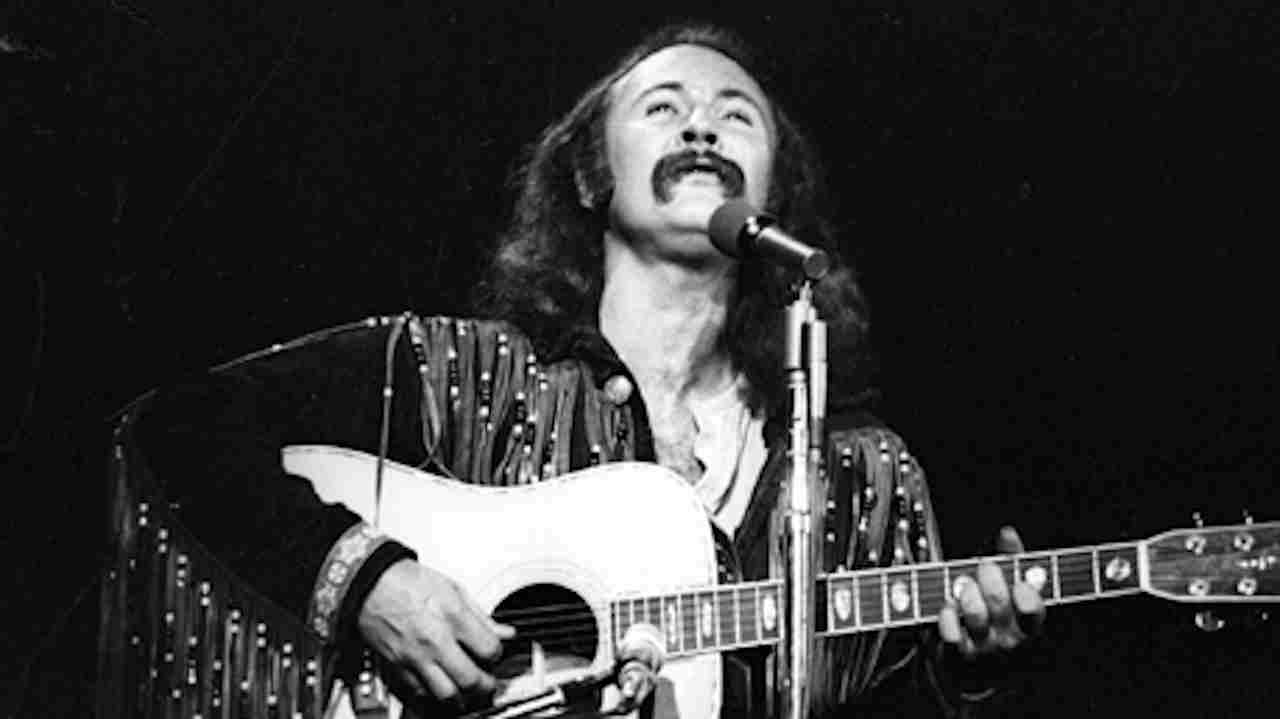

The results were nothing short of staggering. A soft-rock masterpiece of ravishing acoustic guitar, strange modal tunings and breathless harmonies, it all feels of a piece, like the last sustained exhalation of the Aquarian age. There are sliding jazz chords, subtle shifts of light and shade, and an overriding sense of soul-foraging. Nothing captures the latter mood more than Crosby’s intricately-layered harmonies, which sound positively ecclesiastical in their wordless state. Maybe this is what got the Vatican all a-dither.

“That’s the Mormon Tabernacle me,” said Crosby. “I did a lot of that on that record.”

It was a quality not lost on his partner in rock’s high church of vocal harmony, Graham Nash. “The song Laughing is a perfect example of that,” Nash told this writer some years back when the subject of If I Could Only Remember My Name arose. “It’s got incredibly simple instrumentation, but it’s the most giant track you’ll ever hear in your life. All the guitars sound like one great instrument.”

The sessions themselves were loose and informal. “A good half of the album was recorded when we just left the tape rolling,” remembers Barncard. “I’d have this wall of tape machines ready. This was a totally different David at this point. He’d decided to give in to his hedonism and was living with three chicks on the boat. He was up in San Francisco to stay, and was looking for somewhere to live while he was moored up in Sausalito harbour. He liked to work fast and fun, and he’d invite all his friends to come over and hang out. Those sessions were the hottest party in town. You’d have Garcia and Lesh and Bill Kreutzmann hanging out, they were all fans of Crosby. And bear in mind that The Grateful Dead weren’t the big cult band they are today, they were just another San Francisco psychedelic band without a hit record.”

The great centrepiece of If I Could Only Remember My Name is the eight-minute-long Cowboy Movie. But Cowboy Movie is about as overtly lyrical as the album gets. Several songs are more impressionistic, drawing power from musical interplay and the billowy ambience of the monastic harmonies.

Song With No Words is a case in point, with Crosby’s tiered vocal moans seeping through the nimble picking of Garcia and Kaukonen and Santana/Journey man Gregg Rolie’s lovely piano. Tamalpais High (At About 3) employs a similar technique, a dream-weave of guitars which makes for the horizon on the wings of Crosby’s wordless jazz scatting. The tune was named in honour of his dubious habit of driving by the school of the same name as the girl pupils emerged for hometime.

Then there’s the beautiful arrangement of Orleans, a sound picture with Crosby intoning a repeated line that, throughout, barely exceeds a murmur: ‘Orleans, Beaugency, Notre Dame du Cléry, Vendôme, Vendôme.’

Perhaps the most startling example of If I Could Only Remember My Name’s gloriously ad hoc approach is the closing I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here, recorded very late at night with just Crosby and Barncard, wasted and alone, in the studio. It was an improvised flash of brilliance, featuring only an echo chamber and five passes of live vocals, inspired by Crosby’s sudden vision of Christine Hinton. Barncard has called the process “15 minutes of cosmic skydrop. I had never seen the Muse work so magically.”

Crosby revealed that the song simply flowed through him. “I think that’s been the case a lot of times in my career,” he said. “We’re awfully grateful for doing what we love to do, and none of us are really sure how it works. So the feeling that it might be coming somehow through you is very frequent. Nothing’s been quite that intense though. I was very high when we recorded I’d Swear There Was Somebody Here.”

Another song that arrived in a similar manner was What Are Their Names, co-written with Young, Garcia, Lesh and Santana drummer Michael Shrieve. A tune that addressed corporate greed and political corruption in Nixon’s America, it sought to bring people to account. ‘I wonder who they are/The men who really run this land/And I wonder why they run it/With such a thoughtless hand,’ sang Crosby, Kantner, Mitchell, Slick, Garcia, Lesh, Nash and David Freiberg, a grouping Kantner later christened ‘The Great Planet Earth Rock And Roll Orchestra’. It was a number that CSNY revived to stirring effect during their Bush-baiting ‘Freedom Of Speech’ shows across the US in 2006.

“I’d sung it to Neil,” recalled Crosby, “and he’d said, ‘Hey, I’ve heard that before somewhere!’ When I told him I’d done it on my first solo record, he went, ‘Man, that’s very cool. We oughta do that.’ So we did What Are Their Names on that CSNY tour. We’d get the audience going with a chant and then we’d sing the chorus over that. It was pretty intense.”

A couple of the songs on If I Could Only Remember My Name offer a more explicit sense of Crosby’s mourning process. Laughing was a composition that he’d been whittling away at quietly for a few years, but now felt like its time was due: ‘And I thought that I’d found the light/To guide me through my nights and all its darkness/I was mistaken, it was only reflections of a shadow that I saw.’ It’s perhaps the most gorgeous moment on the album, sung with the kind of shimmering delicacy that only Crosby at his best can muster. His back-up troupe were no slouches either, of course, especially Joni Mitchell, whose keening high harmonies are enough to make your backbone twitch.

The wonderful Traction In The Rain also hints at the darkness that had cast a pall over Crosby’s heart: ‘Hard to find a way/To get through another city day/Without thinking about/Getting’ out.’ And then, as if he’s staked out his soul too far in the open already, the second verse resorts to the oblique, enigmatic nature that has come to characterise much of Crosby’s songwriting: ‘Now the strangest thing I’ve seen/Was a T-shirt turning green/In envy of turtle dove/The dove’s lady was the cause/Or maybe it was the olive branch she held in her claws.’ Don’t ask.

What’s abundantly clear, 40 years on, is that If I Could Only Remember My Name is a classic, and arguably the greatest thing David Crosby ever put his name to. It’s also been cited as a key text by a new generation of acoustic-leaning, harmony-driven artists: Robin Pecknold, Portland-based leader of US folk-minstrels Fleet Foxes, says the album “evokes a very strange, woozy paranoia and seems to make no concessions to normal concepts of what an album should be. It’s one of those albums that sets your mind free to wander, no matter where you are.”

Originally published in Classic Rock Presents AOR issue 2