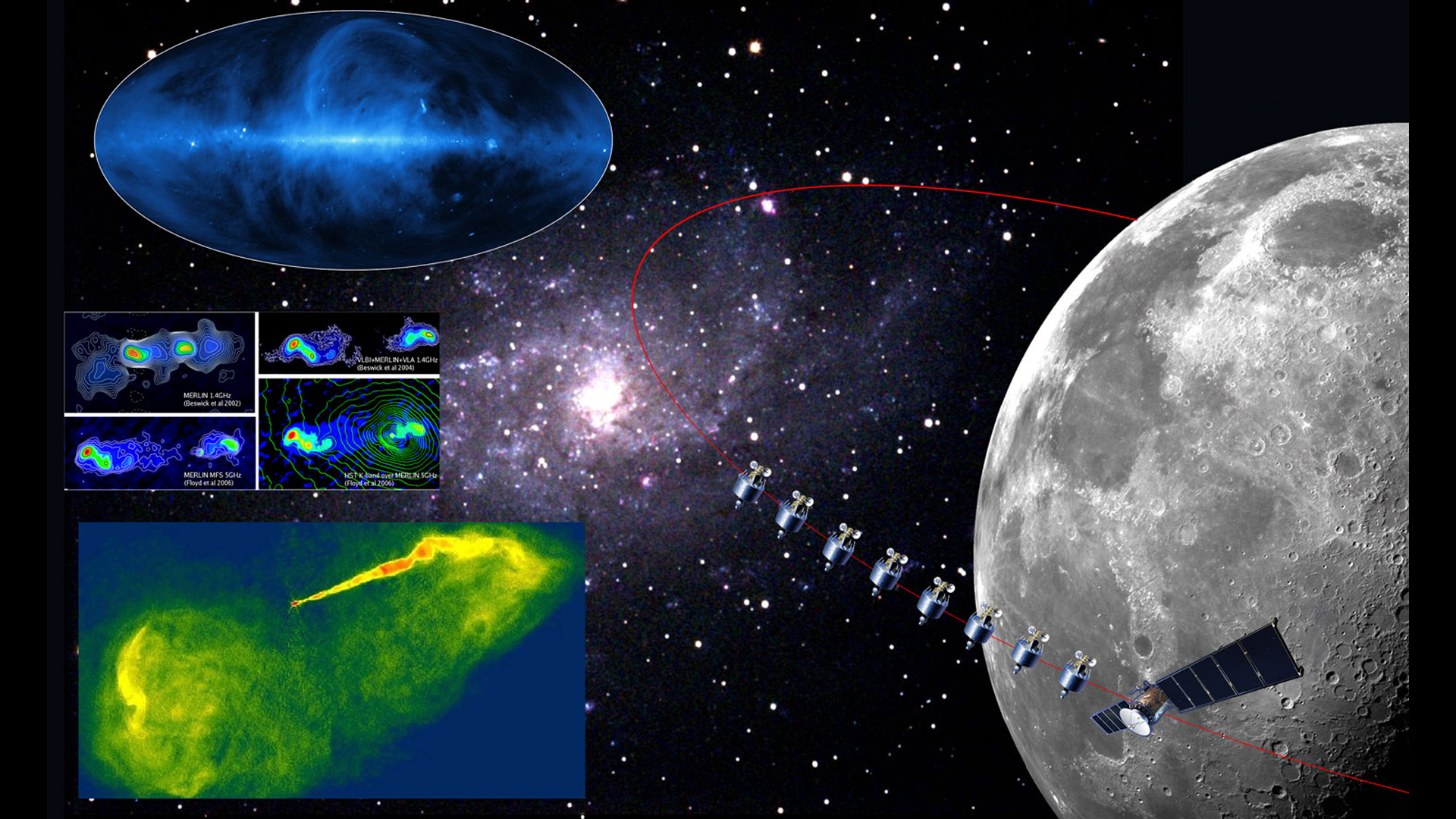

China wants to put a small constellation of satellites in orbit around the moon to create a radio telescope that would open a "new window" into the universe.

The array would consist of one "mother" satellite and eight mini "daughter" craft. The mother would process data and communicate with Earth, and the daughters would detect radio signals from the farthest reaches of the cosmos, Xuelei Chen, an astronomer at the China National Space Administration (CNSA), said at the Astronomy From the Moon conference held earlier this year in London.

Putting such an array in orbit around the moon would be technically more feasible than building a telescope directly on the lunar surface, a venture that NASA and other space agencies are currently considering as one of the next big steps in astronomy.

Related: Radio telescope on moon's far side will peer into universe's 'Dark Ages'

"There are a number of advantages in doing this in orbit instead of on the surface because it's engineeringly much simpler," Chen said during the conference. "There is no need for landing and a deployment, and also because the lunar orbital period is two hours, we can use solar power, which is much simpler than doing it on the lunar surface, which, if you want to observe during the lunar night, then you have to provide the energy for almost 14 days."

He added that this proposed "Discovering Sky at the Longest Wavelength," or Hongmeng Project, could orbit the moon as early as 2026.

Why build a lunar telescope?

A telescope on the moon, astronomers say, would allow them to finally see cosmic radiation in a part of the electromagnetic spectrum that is impossible to study from Earth's surface: radio waves longer than 33 feet (10 meters), or, in other words, those with frequencies below 30 megahertz (MHz).

"If you are looking into the low-frequency part of the electromagnetic spectrum, you'll find that, due to strong absorption [by Earth's atmosphere], we know very little about [the region] below 30 megahertz," Chen said. "It's almost a blank part of the electromagnetic spectrum. So we want to open this last electromagnetic window of the universe."

Astronomers are interested in this part of the electromagnetic spectrum for a good reason. They think this type of radiation might allow them to peer into the so-called Dark Ages, the period of the first few hundred million years after the universe's birth in the Big Bang.

At that time, the fledgling universe was filled with an impenetrable fog of hydrogen atoms. Even when the first stars began to form, their light couldn't get through this haze at first. Astronomers know, however, that this atomic hydrogen itself emits a type of signal known as the 21 centimeter line. Part of the microwave band of the electromagnetic spectrum, the 21 cm line has been helping astronomers track hydrogen clouds in our own galaxy, the Milky Way, since the 1950s, according to astronomer Ian Crawford of University College London.

But when searching for the 21 cm line from the earliest epoch of the universe, astronomers have to look for radiation with much longer wavelengths. As the redshift effect caused by the accelerating expansion of the universe stretches electromagnetic radiation from sources moving away from us toward longer wavelengths, what was microwave radiation emitted by the hydrogen atoms during the earliest epoch of the universe today appears to observers on Earth as long radio waves. And that is exactly the type of electromagnetic radiation that cannot be seen from the planet's surface.

The moon's far side, however, is probably the best place in the solar system to look for this mysterious signal. Far away from Earth's obstructive atmosphere, the moon's far side is also protected from man-made radio noise. During the lunar night, it also faces away from the sun, which, too, is a powerful source of radio waves. Astronomers say that the moon's far side is, in fact, the most radio-quiet place in the whole solar system.

A demo that didn't quite work out

Since radio waves are the type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths, telescopes that can map their sources in the sky with high-enough resolution need to use multiple antennas distributed over a large area. China's constellation would achieve that in space, with the satellites circling the moon in the same orbit. The satellites would gather data while on the far side of the moon. The mother spacecraft would then relay the measurements to Earth when crossing the moon's planet-facing side.

Chinese scientists have previously attempted to test this approach with two microsatellites called Longijang 1 and Longijang 2. The two spacecraft, also known as the "Discovering the Sky at Longest Wavelengths Pathfinder," rode to the moon with the Chang'e 4 mission that landed on the lunar surface in 2019. Longijang 1, however, failed while entering the moon's orbit, so astronomers only received data from Longijang 2. That probe's measurements, Chen said, showed that the moon's far side, indeed, is incredibly quiet.

"We did have the Longijang 2, which circled the moon for some time, and [its] spectrum shows that when the satellite enters the shadow of the moon or comes out of the shadow, you can see where the radio interference appears and disappears," Chen said. "It does show that the far side of the moon provides an ideal environment for this kind of measurements."

Astronomers expect that they would discover much more than the signal of atomic hydrogen from the dark ages. A new, never-before-seen face of the universe is likely going to spring into view once astronomers know how to look for it. Magnetospheres of exoplanets outside the solar system could reveal themselves in long radio waves, and some researchers hope that such an array could perhaps even allow us to make contact with intelligent extraterrestrial life.

"If we open up a new window, we will very likely see some new interesting objects," Chen concluded.