A European experiment aboard China's Chang'e 6 mission has recorded previously undetected charged particles on the moon's surface, a catalog of which enables astronomers to better probe the chemical makeup of the moon's regolith.

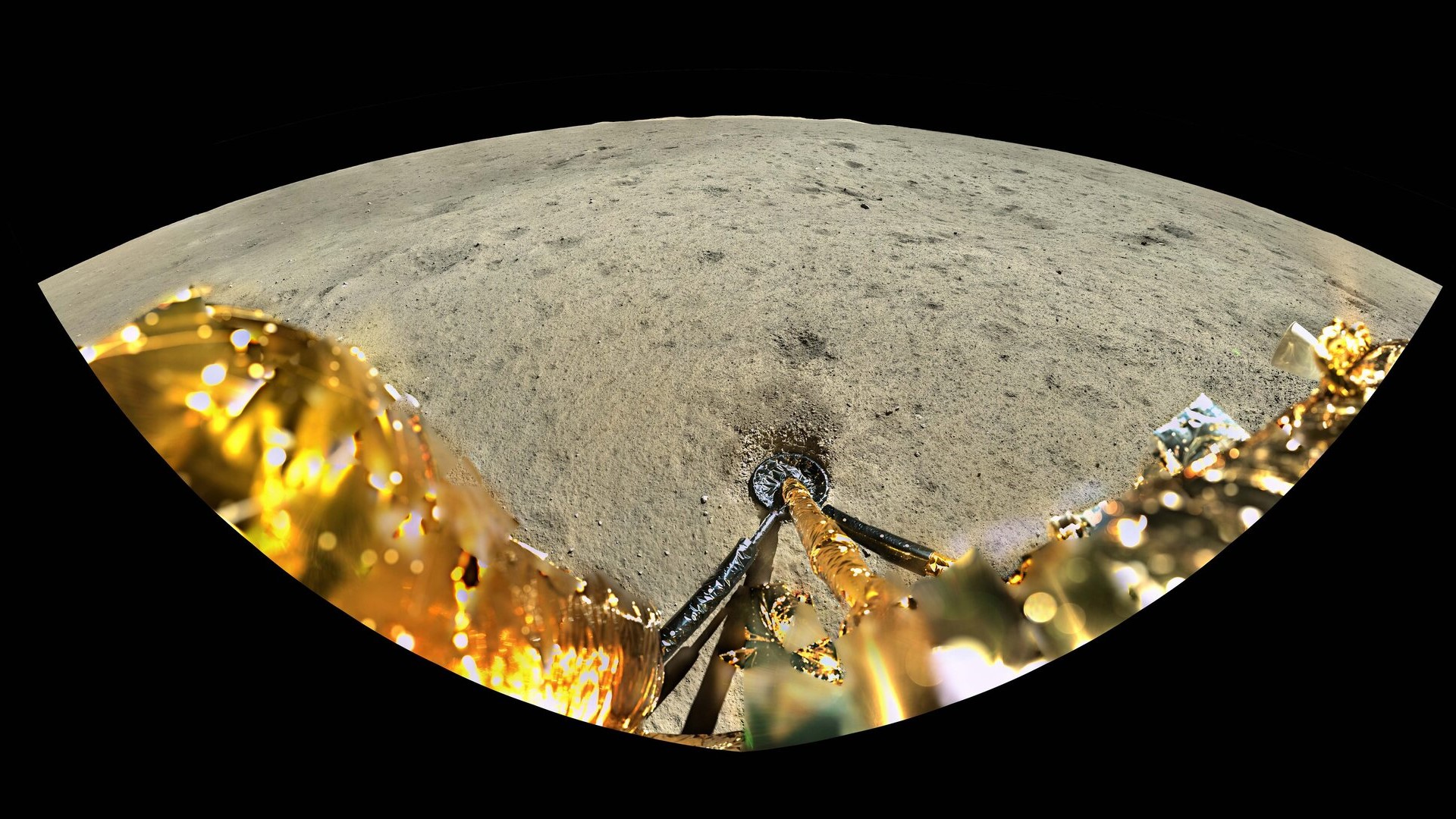

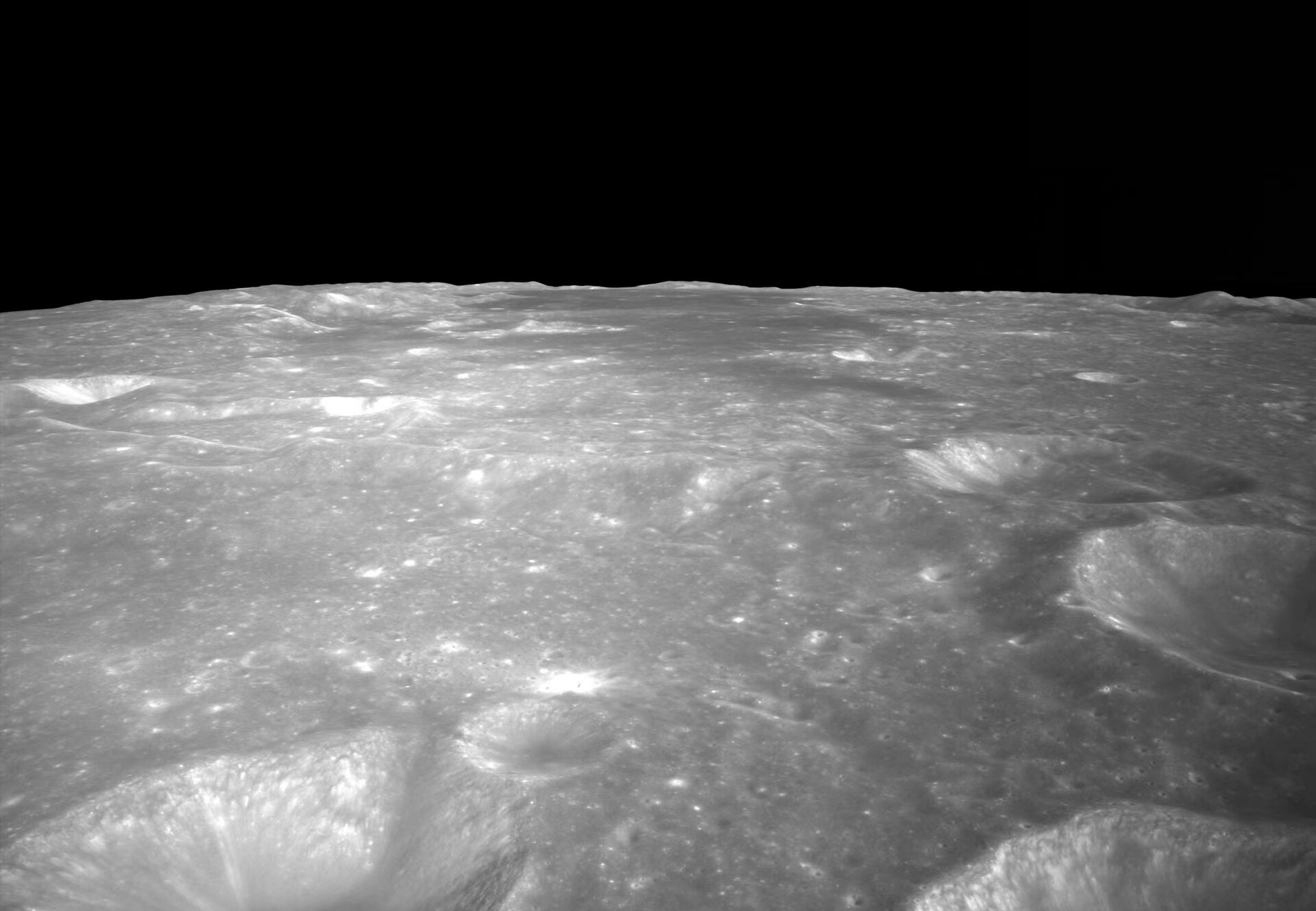

These particles, which are essentially gases excited by sunlight, were detected at the landing spot of the Chang'e-6 spacecraft in the southern pocket of the Apollo crater, which lies within the South Pole-Aitken Basin on the moon's far side. The ion detector was the first European Space Agency instrument to land on the moon.

"This was ESA's first activity on the surface of the moon, a world-first scientifically, and a first lunar cooperation with China," Neil Melville, ESA's technical officer for the experiment, said in a statement. "We have collected an amount and quality of data far beyond our expectations."

While Earth is protected from solar storms thanks to its magnetic field, which repels and traps charged particles from the sun, the moon lacks its own magnetic field. So, gases in its vanishingly thin atmosphere — helium, ammonia, methane and carbon dioxide, among a handful of others — are easily ionized by sunlight and "picked up" by flowing plasma. These charged particles ferry information about the chemical makeup of the moon's regolith, where the gases originate from through different processes rife on the surface, including impacts from small asteroids.

Related: Watch China's Chang'e 6 probe land on far side of the moon in dramatic video

In 2012, a NASA moon mission named ARTEMIS (short for Acceleration, Reconnection, Turbulence and Electrodynamics of the moon's Interaction with the sun and not to be confused with the agency's modern Artemis lunar program) observed pick up ions wafting up 12,400 miles (20,000 kilometers) above the lunar surface. All of them were positive ions, meaning they contained more protons than electrons. Negative ions are short-lived and don't float far from the surface, so they were never detected prior to the Chang'e-6 experiment, scientists say.

Scientists are yet to arrive at an estimate of how many negative ions float near the moon's surface, a number that would have implications for how the moon interacts with the sun, according to the Swedish Institute for Space Physics, which built the ion detector, named Negative Ions at the Lunar Surface (NILS).

NILS started working close to five hours after the spacecraft landed on the moon on June 1. It worked intermittently during the two-day mission, powering through low voltages, communication blackouts and reboots, ESA said. The detector collected three hours of data in total — thrice the required amount for the experiment to be considered a success.

"We were alternating between short bursts of full-power and long cooling-off periods because the instrument was heating up," Melville said in the statement. "The fact that it stayed within its thermal design limits and managed to recover under extremely hot conditions is a testament to the quality of the work done by the Swedish Institute of Space Physics."

Beyond the NILS experiment, the Chang'e 6 mission drilled the moon's surface and scooped up about 2,000 grams of material. Scientists say these samples, which are the first-ever collected from the lunar far side, could offer fresh insights into the formation and evolution of the moon and the solar system.

Once sample acquisition was complete, the robotic lander placed a wooden model of China's five-star red flag on the surface before lifting off and rendezvousing with a waiting spacecraft in orbit.

As of Wednesday (June 12), the samples continue to circle the moon in Chang'e 6's return module, waiting for the right time to kickstart its journey back to Earth. The return capsule is scheduled to arrive on June 25 at the Siziwang Banner in north China's Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region.