China and Southeast Asian nations agreed Thursday to try and conclude within three years a long-delayed nonaggression pact aimed at preventing the frequent territorial spats in the busy South China Sea from turning into a major armed conflict.

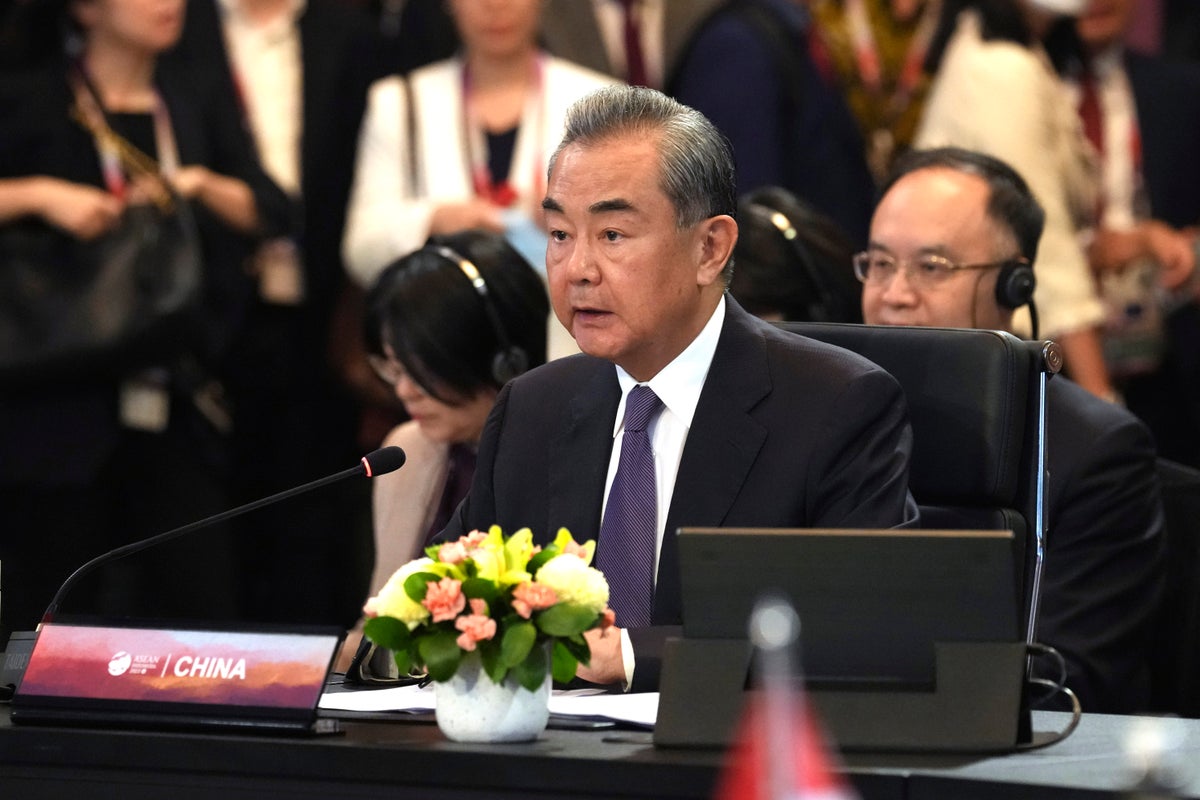

China and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations agreed Thursday during a meeting between the 10-nation bloc’s foreign ministers and China’s top diplomat Wang Yi in the Indonesian capital of Jakarta to guidelines to complete their code of conduct negotiations before fall 2026, a Southeast Asian diplomat involved in the meetings told The Associated Press.

The diplomat spoke on condition of anonymity due to a lack of authority to discuss the issue publicly ahead of the official announcement of the agreement.

China and four of ASEAN’s member states — Brunei, Malaysia, the Philippines and Vietnam — along with Taiwan have been locked in a decades-long territorial standoff in the disputed waterway, a key passageway for global trade that is believed to be sitting atop vast undersea deposits of oil and gas.

The contested territory has long been feared as an Asian flashpoint and has become a sensitive front in the U.S.-China rivalry in the region.

A joint working group by China and ASEAN “should endeavor to conclude the negotiation of an effective and substantive code of conduct, in accordance with international law, including the 1982 U.N. Convention of the Law of the Sea, within a 3-year timeline or earlier,” according to the guidelines, a copy of which was seen by the AP.

The guidelines called for more meetings between the two sides and the start of negotiations for the most contentious issues, including whether the regional code should be legally enforceable and its geographical scope.

Washington lays no territorial claims in the South China Sea but has said that freedom of navigation and overflight and the peaceful resolution of the disputes were in the United States' national interest. It has challenged China’s expansive territorial claims in the region and Beijing has angrily reacted by warning the U.S. to stop meddling in what it calls a purely Asian dispute.

China and ASEAN signed a nonbinding 2002 accord that called on rival claimant nations to avoid aggressive actions that could spark armed conflicts, including the occupation of barren islets and reefs, but violations have persisted.

About 10 years ago, China turned seven disputed reefs into what have become missile-protected chain of islands in the Spratlys, the most hotly contested part of the South China Sea, sparking alarm from rival claimant states and the U.S. and its allies. With tensions rising, ASEAN and China had agreed to negotiate for a code of conduct. But the talks were delayed for years, including during the height of the coronavirus pandemic, and because of major differences between China and rival claimant states.

Chinese negotiators have proposed that the code of conduct restrict the presence and activities of foreign forces in the disputed waters. Southeast Asian diplomats have said that U.S. allies involved in the talks were opposed given their stance that Washington serves a crucial role as a counterweight to Beijing in the region.