When Shifa Zhong thinks about Chicago’s Chinatown, he sees the potential for it to become an escape for the city — like a mini-Disneyland.

People from across the city already visit Chinatown, and he thinks the neighborhood could expand and become a bigger entertainment district.

“My wishful thinking is that hopefully ... Chinatown is that destination for Chicago to become the safest place for everybody, for every resident in Chicago just to eat, have fun, bring the family, bring their dates ... ,” said Zhong, who lives in nearby Bridgeport but often can be found around Chinatown and is behind the Instagram accounts “Chicago Loves Chinatown” and “Chinatown Shifa.”

Some Chinatown neighborhoods elsewhere in the country are facing threats from urban development. For the first time, the National Trust for Historic Preservation listed two Chinatowns — in Seattle and Philadelphia — as among the 11 most endangered historic places for this year.

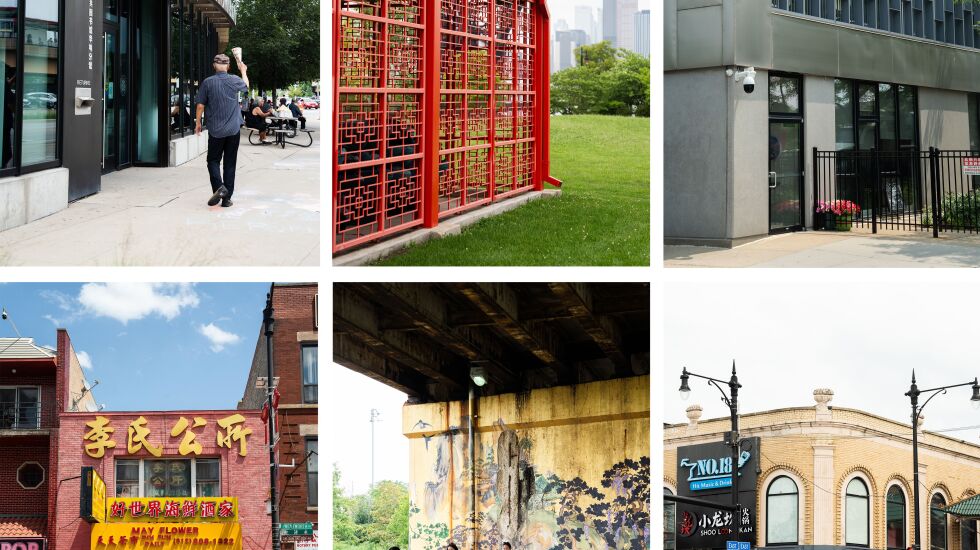

But Chicago’s Chinatown is a traditional Chinese American community that’s growing, expanding into nearby neighborhoods as businesses rebound from the coronavirus pandemic.

From 2010 to 2020, the population of Armour Square — the community area that includes Chinatown — grew from 13,443 to 13,890, according to a Chicago Sun-Times analysis of census data. And the Asian American population increased in neighboring community areas including Bridgeport, McKinley Park, Douglas and the Lower West Side.

Across the city, the 2020 census found that Asian Americans were the fastest-growing racial or ethnic group in Chicago. The Asian American population saw growth of about 31% from 2010 to 2020, meaning the community makes up 7% of all residents, according to a Sun-Times analysis of census data.

Chinese American businesses have spread beyond Chinatown’s bustling hub centered around Cermak Road and Wentworth Avenue. They now can be found miles away along Archer Avenue. On Halsted Street in Bridgeport, restaurants serving various Chinese cuisines have blossomed.

The growing numbers of residents and businesses have translated into political power for the community. The Chicago City Council’s first Asian American female member, Ald. Nicole Lee, now represents the 11th Ward that includes Chinatown. On the North Side, Ald. Leni Manaa-Hoppenworth, the daughter of Filipino immigrants, also recently was elected to represent the 48th Ward.

The growth hasn’t come without bumps. Chicago Public Schools officials’ plans to build a new high school on the Near South Side that would serve communities including Chinatown have been met with controversy over where that school should be built.

“Chicago’s Chinatown is definitely growing,” said Zhong, who on Sunday is hosting the Chinatown Summer Fair. “And since we have the new elected Ald. Nicole Lee, how can we leverage the success or the resources that we have from Chicago’s Chinatown and work with our neighbors — Bronzeville, Pilsen or even South Loop — to continue to thrive?”

Moving away from the Loop

Chicago’s original Chinatown was established in the late 1800s along Clark Street between Harrison and Van Buren streets after Chinese American residents opened a hand laundry business and a grocery store, according to Mabel Menard, the interim executive director of the Chinese American Museum of Chicago.

During that era, the federal Chinese Exclusion Act barred Chinese immigrants from seeking U.S. citizenship and limited the professions they could enter, Menard said.

“Businesses made it easier for [immigrants] to establish themselves because a lot of it was family businesses,” Menard said. “They would live on the premises as well. And also the children, after school ... could help out with the family business.”

Rising rents and discrimination led the community to move just south of downtown near Cermak Road and Wentworth Avenue, according to Menard, who points to a sign for a Mexican restaurant — La Cocina, 406 S. Clark St. in the Loop — in a building with imperial-style architecture as hinting at the area’s past.

“I think that’s one of the reasons why Chicago’s Chinatown is the only Chinatown in the U.S. that’s growing,” Menard claimed. “All the other Chinatowns are either stagnant or actually shrinking. The fact that they’re able to move away from downtown made it easier to expand.”

Ernie Wong, a landscape architect whose design firm has shaped how Chinatown looks, including Ping Tom Memorial Park, near 18th Street and Wentworth Avenue, agrees that the community establishing itself farther from downtown around 1912 made it possible for the neighborhood to expand. More affordable housing in present-day Chinatown made it feasible for the neighborhood to flourish, with growth continuing along Archer Avenue west of Chinatown, Wong said.

“That doesn’t happen in New York — in Manhattan’s Chinatown, it continues to be squeezed,” Wong said.

Other Chinatowns, like the one in Washington, D.C., also are fighting against gentrification, he said: “Just because you put Chinese characters on a Starbucks doesn’t mean it’s Chinatown.”

Zhong said tourism has helped pay for services that keep the community flourishing. The Chicago Chinatown Chamber of Commerce operates a parking lot that tourists pack each weekend, which helps fund programs such as language classes, he said.

“A lot of nonprofit organizations benefit from the commercial success of Chinatown,” he said. “It becomes a cycle — a good cycle.”

Evolving Chinatown

Li Meng migrated from Beijing to Chicago about 25 years ago. She remembers a Chinatown that did not embrace her when she moved to the neighborhood. She spoke Mandarin, and most of the residents at the time spoke Cantonese.

Over the years, Meng said she has seen Chinatown become more inclusive, as shops and restaurants expanded. On a recent afternoon, Meng, who now lives in Oak Park, walked around Chinatown Square with her daughter Rebecca Lu after she got a haircut.

Lu didn’t grow up around many Asian American families, but Chinatown offered her a place to link up with her family’s roots.

“Chinatown is a good place for the Chinese diaspora to connect with our culture,” Lu said.

In addition to pointing out threats to other Chinatowns from development projects such as a new sports arena in Philadelphia, the National Trust for Historic Preservation wanted to spotlight these communities that faced xenophobia during the coronavirus pandemic.

Early on, then-President Donald Trump blamed China for the pandemic, and Asian American communities across the country saw increases in harassment. It also created economic hurdles for businesses, said Di Gao, senior director of research and development for the National Trust.

“It really felt like there was a real opportunity to do more as the national preservation organization to spotlight Chinatowns, to elevate Chinatowns as these cherished, important cultural and historical neighborhoods and assets for our country,” Gao said.

Spencer Ng’s family has owned Triple Crown Restaurant, 2217 S. Wentworth Ave., since the mid-1990s. He remembers customers reacting rudely when one of the restaurant’s workers wore a mask in the early days of the coronavirus pandemic. Not long after, the restaurant started getting prank phone calls.

Ng said Triple Crown focused on providing meals for the community and first responders as the economy started to recover. Still, the restaurant is operating at about 65% of its capacity as he’s struggled to find workers after many left the service industry.

“We’re still here,” Ng said. “We’re grateful and thankful, but we’re still not 100% yet.”

Menard said Chinatown still serves as a hub to welcome Chinese immigrants, though there are differences in dialects and languages. Newer waves of immigrants have lived in a politically different China and might not have experienced the turmoil of that country’s cultural revolution as past generations did, she said.

“I think there is still the whole sense that we’re all of Chinese descent, so there is still the mentality and the need to support and help one another,” Menard said.

The newer generation of Chinese immigrants is coming from modern cities like Shanghai and Beijing, which could shape the future of Chinatown’s architecture, Wong said.

“This is not your grandmother’s Chinatown,” Wong said. “So I think there’s an evolution that will occur. But I think that there is still an appreciation for the preservation of a lot of these buildings that have been used in formulating Chicago’s Chinatown.”

The neighborhood is home to some buildings designed by prominent architects:

- The Chinese American Service League Building, designed by Jeanne Gang’s Studio Gang and built in 2004.

- The Chicago Public Library Chinatown branch, by Brian Lee of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, built in 2015.

- Archer Courts, by Landon Bone Baker Architects, built in 1999 and 2004.

The Pui Tak Center, which offers community programs such as citizenship classes and youth activities, is the neighborhood’s only structure to have a Chicago historic landmark designation. It was built to house the On Leong Merchants Association.

Ward Miller, of the group Preservation Chicago, says there aren’t many landmarks citywide that pay homage to the city’s Asian American communities. But there is precedent in other communities like Little Village’s archway that indicates similar efforts could be made in Chinatown.

“I think that would be a great honor to the Asian community to recognize some of these buildings,” Miller said. “And, of course, there are benefits to being a Chicago landmark or landmark district, and I think that would be a great planning tool.”

Historical designation can be a powerful tool for communities, but property owners in Chinatowns might not embrace the additional oversight on buildings, Gao said. That’s one of the reasons the National Trust for Historic Preservation is hosting conversations with community leaders about what other strategies could help preserve these cultural hubs, she said.

Zhong said he thinks every building in Chicago’s Chinatown should have a historical landmark designation. He thinks this could be especially important as The 78 project — a new neighborhood being built that will border the area — gets off the ground.

“I think becoming a historical landmark can help us stay here,” Zhong said, pointing out that some businesses already are seeing an uptick in rents.

Some community residents think this new project will drive more business to the area. Others are concerned about increasing housing costs. The 78 is now building the Wells-Wentworth Connector, a pedestrian- and bike-friendly path that will connect Chinatown to the Loop, according to developer Related Midwest.

The developer said it has held community meetings to hear from people in Chinatown as the project moves forward.

In a written statement, Related Midwest said, “And by creating the Wells-Wentworth connector, a brand new road through the site, the 78 will bring new amenities close to Chinatown and make Chinatown’s many businesses and cultural attractions easier to access from downtown.”

But Zhong also thinks the type of businesses in the area could diversify and serve as a bridge for surrounding communities. He said he already has seen signs of a younger generation taking over businesses and attracting new people.

Zhong’s latest project involves public relations for Vital Chinatown, a new, luxury sneaker shoe store on Cermak Road. The owners thought a Chinatown location would work not only because they are an Asian-owned business but because it could bring in customers from Pilsen and Bronzeville.

“Is it possible for Chicago’s Chinatown to become a neutral ground for everybody?” Zhong wondered. “Chinatown [could] become the safest zone, the most peaceful community in Chinatown because everybody’s agreed to that.”

Elvia Malagón’s reporting on social justice and income inequality is made possible by a grant from The Chicago Community Trust.