Last month, 19-year-old Alonte Wilson put on a moss green cap and robe and got his high school diploma.

A few years earlier, the odds of this achievement were low. He dropped out of school during the pandemic, like thousands of other Chicago Public Schools students. Then he got shot. He also got arrested. He was so far behind that when he tried to go back to his neighborhood high school, Wilson got discouraged and gave up.

In the 2021 school year alone, 16,000 students stopped coming. CPS officials decided they needed to do something to bring these students back. They set an ambitious goal of reaching 1,000 students who had been away from school for more than a year. The school district got an $18 million grant from the state for the work.

This was not just an education initiative: 90% of school-age victims of gun violence, such as Wilson, were not engaged in school at the time they were shot, according to University of Chicago research.

Wilson got a second chance through the CPS pilot program, called Back to Our Future, which aims to engage the hardest-to-reach kids: students who have been disconnected from CPS for more than a year, and are at high risk of being involved in gun violence.

But according to a new University of Chicago analysis, Back to Our Future is struggling to connect with the kids targeted by the program. And even those who sign up are not participating at the intended level.

In the first pilot year, 446 students joined the program, 32 students have completed high school, and another 71 students have reengaged in school, according to CPS.

CPS officials and University of Chicago researchers say they are learning a lot and fine-tuning the effort.

“We knew it was going to take relentless outreach to get them to buy into the program and then subsequently participate on a regular basis,” said Jadine Chou, head of safety and security for CPS. “It has lived up to all the challenges we expected it to live up to, it has been very difficult, but we knew that was going to be the case. If this was easy, someone would have already done it.”

Chou says she is pleased with the number of students the program has reached so far.

“These are young people who would not have engaged in school if not for Back to Our Future,” she said. “Every young person in that group is definitely worthy of achieving their educational goals and that’s what this program seeks to do.”

Added Kim Smith, director of programs for the University of Chicago Education Lab and Crime Lab, which studied Back to Our Future: “The city of Chicago has not ever really prioritized this population of young people … What we learned, I think, in the first year is that there’s still a lot of work to do … to make sure that young people are actually coming into programming.”

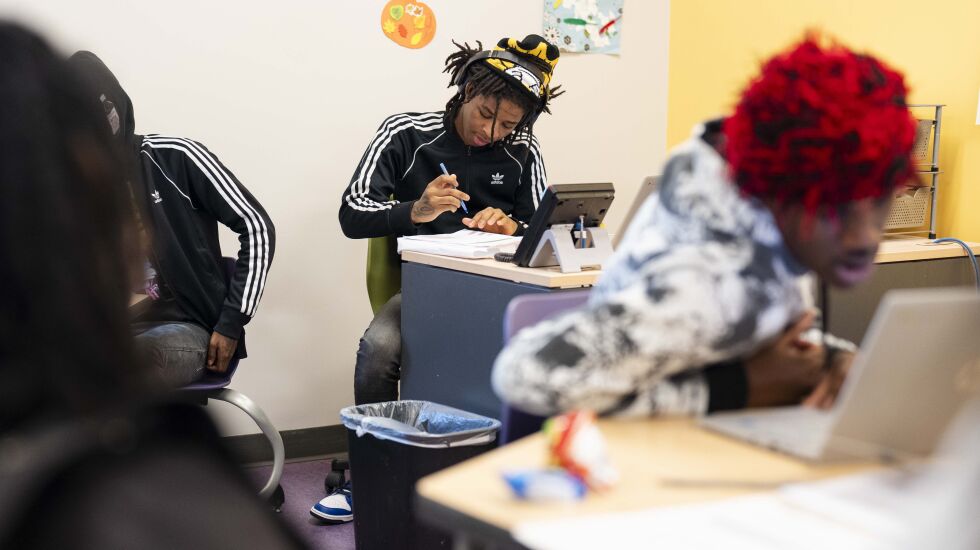

Back to Our Future launched in May 2022, and the analysis studied the first year of the program, ending in May 2023. It paid the 446 participants to take part in 12 weeks of training, therapy and credit recovery and then worked with them to make a plan to graduate or continue their education over a 12-month period. Some students, including Wilson, are getting diplomas through online credit recovery at a community-based organization, rather than returning to a high school.

Those students spent an average of seven hours per week engaged in the program, less than half of the 20 hours they were supposed to attend, according to the report by the crime lab, which also supported its implementation.

Smith acknowledged it is a “costly” program, but said “our failure to invest in this population of young people is what got us here in the first place.

“So I would hope that we wouldn’t shy away from really giving them the support that they need,” Smith said. “But we know that the cost of gun violence involvement is incredible. And it comes at the cost not only to the victim, but to their family and to their friends.”

More worrying than the price tag was the struggle to get kids to participate in academic classes or credit recovery. In both the number of students who participated and in the average number of hours spent, the program failed to meet even 50% of its goals.

But Chou said participation has been increasing as time goes on. She said teenagers often have to experience something before they buy into it. For example, participation in therapy was low, but when asked what they valued most about the program, many cited that component.

Wilson’s success in the program highlights the opportunity to get kids on track if they’re offered the right mix of help and leniency.

Wilson joined the program after a worker from Breakthrough Urban Ministries in East Garfield Park reached out to him. Wilson said instead of making him feel bad about being so far behind, as his former school did, Breakthrough workers offered him intensive help he couldn’t get from CPS. They wrote letters to the judge overseeing his criminal case. And Breakthrough workers picked him up when there was no one else to drive him to the program after he said didn’t feel safe getting there on his own.

Smith said the first year has been a learning experience, as they focus on finding ways to personalize the services being offered.

The problem is so few kids like Wilson being engaged.

The Crime Lab used CPS data to identify 2,000 kids disconnected from school for at least a year and “at high risk of being involved with gun violence.” But only 5% of those kids agreed to participate. The rest of the participants were referred directly by three partner organizations or other institutions, suggesting that relationships between youth and service providers are factors for teens when deciding whether to participate, the researchers wrote.

Chou said all of the students participating had been out of school for an extended period of time.

Myisha McGee, a director at Breakthrough, says some kids don’t feel safe coming to the neighborhood where Breakthrough is located or live too far away to attend.

But she said a much bigger issue was finding kids who had been referred by CPS.

“Numbers change, addresses change, people move … So we might get an aunt, and the aunt is like, ‘Oh, he doesn’t live here anymore,’ ” McGee said. “So we’re always thinking of ways to reach students. We do phone attempts, we do home visits, our outreach team will visit neighborhoods and check social media. So we’re going above and beyond to find these students.”

McGee says when they are able to sign up a student, it often will lead to other referrals of kids who have been out of school.