Censorship of marginalized voices on social media is as old as social media itself.

But such incidents often happen to individuals who feel powerless to change what’s happened and have little knowledge of the scale of misfiring moderation algorithms and questionable human decisions.

However, a new project from British photographer Rankin called The UNSEEN aims to provide strength in numbers to the silenced, bringing together individual stories of hundreds of people who have been censored or shadowbanned.

“Although art and outrage have always been somewhat synonymous, in a simpler time the debate over what was deemed ‘acceptable’ was much slower and I think more open,” says Rankin (real name: John Rankin Waddell) via email.

“But with the online world, these decisions are made behind a curtain, and often not by human beings with empathy but by AI,” he adds. “Algorithms end up stripping creatives, individuals, and even some brands of an audience before they’ve even had a chance to be seen — hence The UNSEEN.”

The project stemmed from a documentary on social media and its impact on society at large by Hunger magazine, which is published by the Rankin Creative agency. “There was one particular line that stood out to us as not really being true,” says Luke Lasenby, creative at the Rankin agency. “It was, ‘We don’t need the middleman to push out an image. When the image resonates, it resonates.’”

So Lasenby and his colleague Opal Turner, who works with the online disability community, set out to highlight the issue in a more nuanced way. “Media platforms are a tool, and they can be used correctly or incorrectly,” says Turner. “Censorship is a tool that can be used correctly and incorrectly.” Both Lasenby and Turner felt that social media platforms — as well as society as a whole — could learn from their past missteps to change their approach to content.

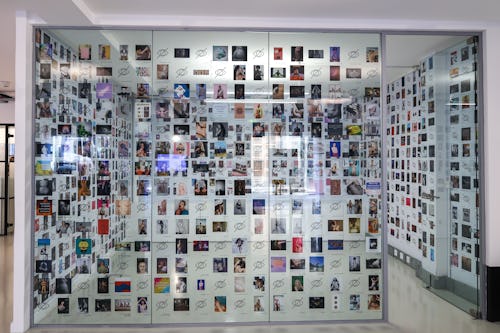

“We naively were just planning on doing a double-page spread on the issue in Hunger,” says Turner. But public response to an Instagram post calling for fans to share their experiences with censorship and moderation online hit a nerve. Rankin Creative has received more than 350 submissions from aggrieved social media users to date.

These submissions are housed on THE UNSEEN’s website, accompanied by interviews with the subjects. There are, not surprisingly, plenty of sex workers who’ve been censored. In addition, there are folks like Mesha Moinirad, who has a colostomy bag, and Talk to Coco, one half of a Black LGBTQ+ couple who says they’ve been shadowbanned by big tech platforms. Another participant, Lakyn, was given a content ban by TikTok for showing a scar related to his disability.

“It’s about giving voice to people that have been unfairly sidelined,” says Lasenby.

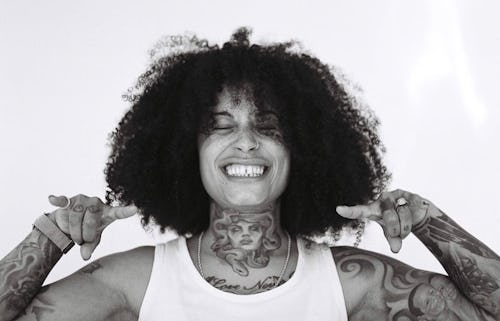

Thirteen of the 350 respondents were invited to be photographed by Rankin himself for a recent IRL exhibition at Quantus Gallery in London, meant to highlight the inequity of censorship.

Among them was Dr. Carolina Are, an innovation fellow at Northumbria University, UK, investigating the link between online abuse and censorship. (Input has previously written about Are’s run-ins with TikTok’s overly censorious moderators, who struggled to accept Are’s hobby: pole dancing.)

Her reasoning for taking part was simple. “It’s all well and good to publish research about this stuff,” says Are. “But for research to have impact, it needs to be translated into something visible and accessible to everybody. It’s also fucking cool to be photographed by such an iconic photographer.”

Tessa Kuragi, a model from London, was another person Rankin photographed for the project. “I’ve been on Instagram now for several years, but I would say in the last year or two I’ve noticed much more of my photos being reported,” she says. When she appeals their blocking, around 80 percent are reinstated after review. Kuragi says she has written five messages to Instagram appealing her image takedowns, none of which have received a response.

In early June, Kuragi’s entire Instagram account — which mixed images of her modelling clothes with her wearing none at all — was suspended for repeated breaches of the rules. She corralled support from her fans and friends to report the account as missing to Instagram, and it was reinstated on June 19. When she spoke to Input on June 21, it had been deleted again.

“My modeling and art work isn’t my main job,” she says. “I have another job, thankfully — but it does mean the modeling side of things is massively impacted.” She says one U.S. brand that contacted her to do paid promotional work pulled out when they realized earlier on that she was being shadowbanned. “It’s huge,” she says.

Kuragi responded to Rankin’s social media callout because she’d previously been photographed by him. She still doesn’t really know why she’s repeatedly received what she thinks are automated content strikes, but one of the messages she frequently gets when a photo is taken down is that she’s breached rules on sexual solicitation.

She says she’s spoken to someone who has a friend working at Facebook (which owns Instagram) who said any mildly sexy post with people tagged in it was seen as solicitation. So she spent hours de-tagging accounts on every post, even though it removes the ability to credit the photographers and makeup artists she works with.

‘Massive’ problem

“There have been campaigns on social media before, and it’s usually been focused on one marginalized group,” says Turner. (Input has previously reported on the activism of fat, Black femmes who feel they’ve been unfairly targeted by Instagram.) “Our point was that this is huge, it’s massive. Groups who you’d think, Surely you’re not still being marginalized online? Newsflash: We absolutely are.”

That’s something Are found particularly powerful about The UNSEEN. “I think there’s a wider issue with people caring about censorship only when it affects them,” she says, “but censorship of nudity and the body started with FOSTA-SESTA and is now trickling down to everybody.” For Are, there is strength in numbers. “Only by doing something really big, and really mainstream, gathering everybody together, do we have power.”

For Are, seeing all those people’s photographs at the Quantus Gallery was a powerful moment. “This has an offline effect,” she says. “Seeing that in an actual room was quite something. It was a way of bridging the physical and the digital and showing how they combine.”

“We want this project to prompt a productive conversation,” Rankin says. “This isn’t about pointing the finger and being accusatory. We’re inviting these online platforms and the wider industry to join the discussion, with those who are being affected, in order to find public and community-based solutions.”

Rankin hopes that a panel discussion he hosted at the massive creative marketing festival Cannes Lions earlier this month will help start the conversation with the big tech platforms behind many of the issues users face. “By joining forces to shine a light on unfair online censorship practices,” he says, “we can work together to make The UNSEEN seen and make existing and future technologies more equitable.”

That’s also what Kuragi wants to happen. “It’s a huge problem, and I think UNSEEN reflects how big the problem is, rather than it being individual people trying to speak up about something,” she says. “I hope it forces a review, because I don’t think the current way of operating is working.”