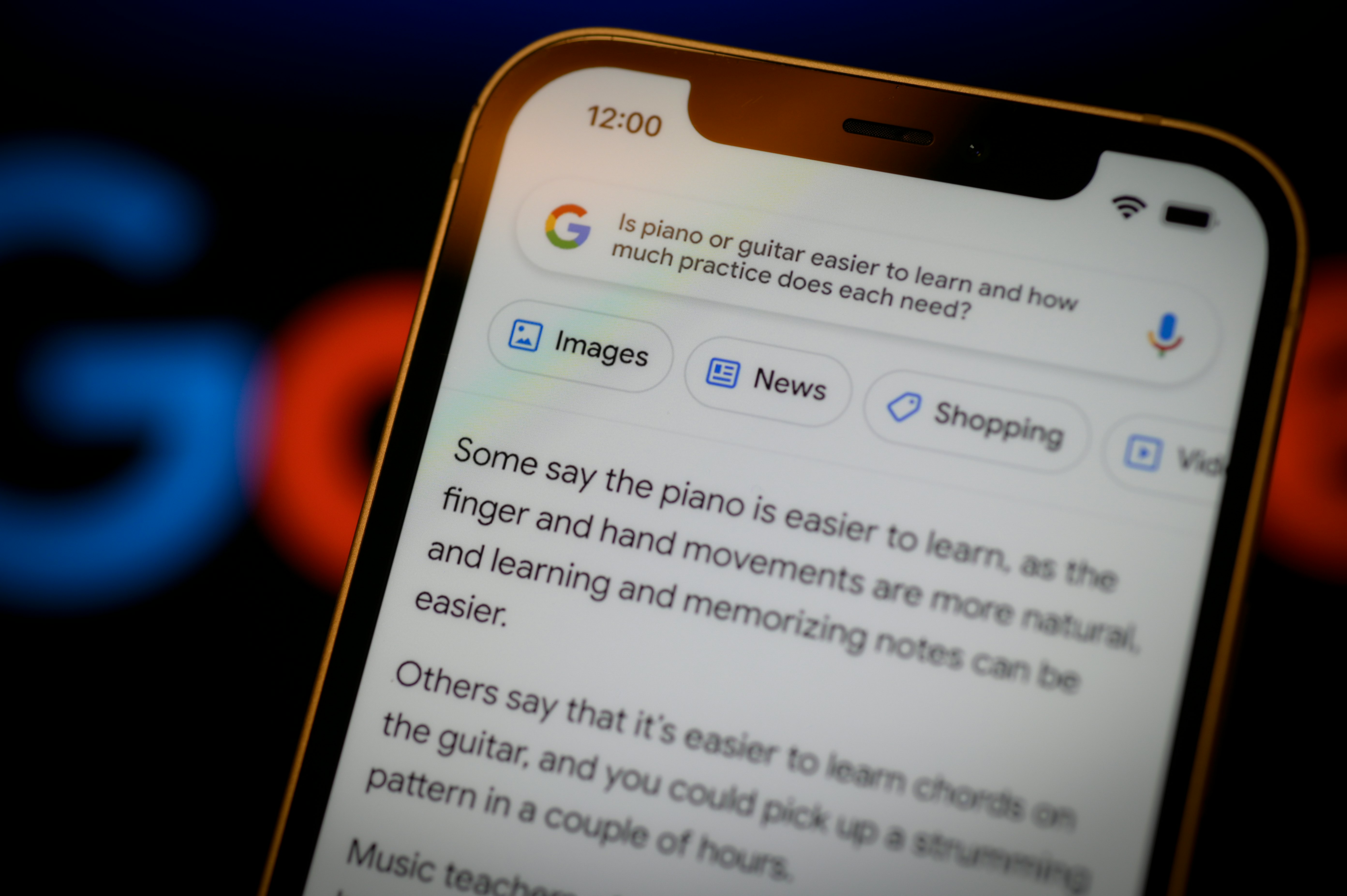

In recent weeks, tech giants have shown off shiny new weapons in the AI arms race: Google, Microsoft, and a handful of other companies will incorporate chatbots into software and search engines, where they can respond to the most random of questions (“Why is there not nothing?”), draft up messages to friends and colleagues, and even woo crushes.

The blitz began with the raging popularity of ChatGPT, which likely propelled the companies to hitch a ride on the chatbot train.

This trend could change the search experience forever — and it may make internet searches a lot easier, according to Joseph Seering, a postdoctoral researcher at Stanford University’s Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence.

“Chatbots, and particularly the ones with open-ended conversation capabilities, are a very convenient interface format,” Seering tells Inverse. Soon, we may no longer have to sift through heaps of websites to get the answers we’re looking for or carefully word our queries.

For example, imagine asking Google or Bing for cozy soup recipes and gleaning solid answers through a quick, entertaining back-and-forth, rather than scouring multiple pages across the web that often yield unsatisfying results.

ChatGPT frenzy

But how did we get here in the first place?

The recent AI hubbub was sparked by ChatGPT, a conversational bot created by the San Francisco-based artificial intelligence company, OpenAI. This tool emerged from a more robust deep-learning language model called GPT-3, but stands strong on its own: Engineers trained ChatGPT on around 300 billion words. You can now order ChatGPT to write poems, songs, and even do your homework (albeit with some errors).

In fact, the hype surrounding ChatGPT may have pushed Google to unveil Bard earlier than planned, says Toby Walsh, chief scientist at the University of New South Wales’ Artificial Intelligence Institute in Australia. After all, the chairman of Alphabet, Google’s parent company, admitted that employees didn’t think Bard “was really ready” yet, CNBC reported.

Google announced its chatbot Bard on February 6, which it claims will “deepen our understanding of information.” Just a day later, Microsoft said it will jazz up its search engine Bing with ChatGPT. That same day, the massive Chinese company Baidu put its hat in the ring, followed shortly by Alibaba.

Given the grip that businesses Facebook and Microsoft already hold over our daily lives, these algorithms could soon upend the way we interact with our devices and each other — for better or worse.

Where it all began

AI-authored text is nothing new: Scientists created the world’s first chatbot program — a computer therapist named ELIZA — in the mid-1960s. We’d consider it pretty basic these days, but at the time ELIZA was considered so advanced that some people thought they were messaging a human. Chatbots have taken major strides in the following decades, particularly in recent years as generative AI ramps up. These types of algorithms help chatbots spit out essays, images, and even videos.

Google and OpenAI have led the generative trend — the former has spent the last few years developing a group of advanced language models (called LaMDA) that now power Bard, while OpenAI’s GPT models serve as the backbone to many fancy new AI-powered tools at Microsoft and beyond.

Earlier this month, Microsoft flaunted a host of new automated features that could affect how wide swaths of people work and socialize. The company included features powered by GPT-3.5 in the publicly available premium version of Teams, such as writing up meeting notes and laying out potential work tasks. And Walsh predicts that GPT will soon pop up in Word to write entire paragraphs, Outlook to type out whole emails, and Powerpoint to prepare presentation slides.

As for chatbot-powered search engine features, the public can’t yet access Bard, but you can sign up for the waitlist to test Bing’s ChatGPT feature (just take a spot in line behind millions of people). So far, these tools have brought mixed results. For one, Bard made a noticeable error in its live demo — which caused Alphabet’s shares to tank by $100 billion. And it turns out that Bing also botched its first public demo.

Still, the current wave of chatbots is “actually quite technically sophisticated and represents an impressive leap forward even from five years ago,” Seering says. “The key here is to set expectations appropriately for what they can and cannot do — presenting a chatbot as an all-knowing oracle is ridiculous, but presenting it as a useful but flawed tool is much more realistic.”

Over time, language models inherently improve as they take in more data, Walsh notes, and it may even get to the point that chatbots make fewer mistakes than people do.

The positives

Beyond making internet searches feel less frustrating, chatbots could cut down the time it takes to complete annoying tasks, like typing out monotonous work emails or contacting a customer service department for a refund.

In fact, chatbots could make any type of software easier to use — these models can take your previous tasks into account and pre-emptively understand your goals, Walsh explains. It’s somewhat like always having a close friend on hand who can finish your sentences and knows when you need a pint of ice cream before you even ask.

So while you may feel a Luddite urge to ignore Bard and ChatGPT completely, you could ultimately form an intimate and beneficial relationship with these types of models. They could even make computers feel more human, according to S. Shyam Sundar, director of Penn State University’s Center for Socially Responsible Artificial Intelligence who studies the psychology of human-computer interaction.

“Chatbots provide human-like agency to an otherwise impersonal transaction between a company and its customers,” Sundar tells Inverse. “Our research has long shown that people tend to look for sources, ideally human-like sources, to orient toward when they engage in online communications.”

So while headlines often paint a picture of doom and gloom, AI models could make our time spent with tech more pleasant.

“Thoughtfully-designed chatbots can certainly have positive effects on our daily lives across a range of contexts,” Seering says. “There have been numerous studies showing this.”

Keep things in perspective

Despite the potential positives, widespread use of these models could come with risks. Beyond the temptation to automate what were once heartfelt texts and emails to friends and loved ones, we could face even more surveillance and data grabs from tech giants.

For example, Google and Microsoft will need new cash flows going forward: When chatbots answer our questions in search engines, we longer necessarily need to click on any links — a major source of income for these businesses. It also costs a lot of money to run these queries, so only a few companies can afford to do it in the first place.

So it’s possible that a small number of major players will try to capitalize on the personal data that we feed to language models, and not to mention will try to control how long we spend on their websites. In the future, you may not even need to visit WebMD to skyrocket your medical anxiety.

“I think it's likely that our interactions with chatbots will be monetized in some fashion going forward,” Seering says. “At the very least, this seems like a very high-quality dataset for use in targeting ads.”

What’s more, even if chatbots reduce the number of factual errors going forward (and there are many) it will be difficult — if not impossible — to avoid the biases baked into an AI by its developers or enforce the “guardrails” built into these models to hinder misuse.

“Some [chatbot problems] are not gonna go away,” Walsh says. “It’s still gonna be challenging to ensure that it doesn’t say things that are offensive or racist or sexist.”

To avoid chatbot chaos, we can’t take their human-like knowledge and behaviors too seriously, Seering says. So even if Bing claims it’s watching engineers through their webcams, appears to gaslight users, or even excels at flirting, it’s crucial to keep things in perspective.

“It's extremely important to avoid anthropomorphizing chatbots like ChatGPT, which is math plus data plus rules and should be treated as a tool rather than an entity,” he says. ”It's easy to fall into the trap of assigning it a character, but this grants it a sort of mystique that can obscure what it does in harmful ways.”