Bushfires cause catastrophic biodiversity loss across Australia. In the Black Summer of 2019–20 alone, 103,400 square kilometres of habitat went up in flames.

The irony is, laws to protect native vegetation did nothing to prevent this destruction. This is because, in most states, these laws make it hard for private landholders to burn on their own land, meaning more fuel is left to feed bushfires.

We have a chance to change that now in South Australia, where the Native Vegetation Act is under review.

With greater knowledge and understanding of the role of fire in the Australian landscape, we can take better care of native vegetation on private land as well as public parks. There’s a strong case to be made for private landholders to conduct their own cool burns, for dual purposes of reducing fuel load and restoring ecosystems.

Fire can be good for biodiversity

A wide range of species will benefit from good fire management, which creates a patchwork of different ages of vegetation.

Some plant and animal species are found only in long-unburnt vegetation. Others need recently burnt areas. Many shrubs only occur in areas burnt in the past 15–20 years.

Fire is also needed to maintain food supplies for many threatened animals. For example, the glossy black-cockatoo feeds almost exclusively on the seeds of drooping sheoak trees. But seeds become scarce in long-unburnt vegetation.

Breaking up the landscape should also mean fewer animals will be caught in each fire, because they have places to which they can escape.

Managing fire at landscape scale

Proactive burning can reduce wildfire risk under most conditions, when managed at the whole-of-landscape scale. This requires everyone to manage fire on their own land in a coordinated way. Such an approach emulates Indigenous land management and was partially adopted by land managers in southern Australia until the 1970s.

Private landholders are no longer allowed to contribute to these efforts, perhaps because the community distrusts both farmers and fire. However, without landholder involvement, fire management capacity is severely limited.

For instance, National Parks and Wildlife Service South Australia’s Burning on Private Land program has managed only 28 hectares of fuel reduction burns on Kangaroo Island since Black Summer. Given forest fuel loads can reach dangerous levels six years after bushfire, the next big one may not be far away.

Climate change means catastrophic bushfires will happen more frequently. Addressing this escalating risk requires allowing landholders to manage fire hazards on their own land.

The devastating Black Summer wildfires

The Black Summer fires killed an estimated three billion animals and drove at least 20 threatened species closer to extinction.

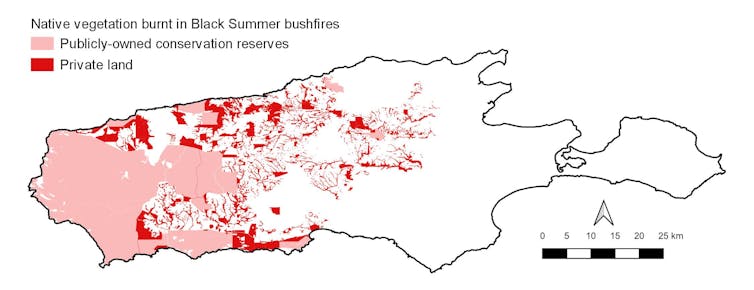

Human lives were lost, livestock perished. More than half of Kangaroo Island burned, including areas that had not seen fire since the 1930s. Along with 96% of Flinders Chase National Park, about 40,000 hectares of native vegetation burned on privately owned land.

While nothing could prevent the spread of fires under catastrophic weather conditions, many of Black Summer’s fires started earlier. They may have been better controlled, or stopped altogether before conditions got out of hand, if the vegetation was not so thick and connected. The very small amount of fuel reduction being undertaken on private land is inadequate.

Burning does not equal land clearing

In 1985, SA introduced the first laws in Australia to protect native vegetation. These effectively stopped the widespread clearance of native vegetation in the state.

However, they have done little to maintain or restore its ecological condition. Since the laws were passed, we have learned more about the effects of fire in Australian landscapes. We now know proactive use of fire can make vegetation more complex and biodiverse. So, fire needs to be actively managed, not excluded.

While well-intended, the existing legislation discourages burning by private landholders, making it almost impossible for them to take responsibility for reducing fuel loads on their own land. This is because South Australia’s Native Vegetation Act defines all burning as clearance.

What do other states do?

Both New South Wales and Western Australia also classify burning as clearing. In Victoria, approval for burning on private land is managed at the local government level and appears to have no provision for ecological burning.

Elsewhere, burning is only considered to be clearance when it is intentionally used for the purpose of destroying native vegetation, as in Tasmania, Queensland and the Northern Territory, or remnant trees, in the case of the Australian Capital Territory.

All states and territories allow exemptions for the purpose of bushfire prevention or fire fighting. None has incorporated fire management for ecological purposes into their native vegetation legislation.

An opportunity for legislative change

So far, proposed changes to the SA Native Vegetation Act have missed an opportunity to reduce wildfire risk across the state.

This could be fixed by simply changing the definition of clearance to exclude fire used for ecological purposes. This is effectively the case in Queensland, where fire is only considered to be clearing when it is specifically used to destroy native vegetation.

SA’s Native Vegetation Council would then need to provide guidance on how landholders should burn to both reduce fuel loads and benefit biodiversity. This should extend the current advice to provide the type of detailed ecological and operational information that is provided in Queensland.

Changing South Australia’s Native Vegetation Act to facilitate fire management by landholders is one step we can take to minimise the risk of catastrophic wildfires. The next steps are trusting landholders to take this responsibility seriously and help them do so. This would bring South Australia back to the forefront of native vegetation management in Australia.

Gabriel Crowley is a former member of Kangaroo Island Landscape Board, and is on the Kangaroo Island Bushfire Management Committee. The author's views expressed here do not represent those of either organisation.

Stephen A Sutton does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.