As with every humanities discipline, classics has responded to Black Lives Matter with justifiable introspection. As the study of the ancient world, and particularly that of the Mediterranean cultures, classics has a significant colonial legacy: British, French and Italian colonialists saw themselves as inheriting or continuing a “civilising mission” which they associated with the Romans. They assumed that the Romans shared their prejudices, particularly those associated with elitism and racism. When they thought about or represented Roman imperial history, they imagined it as dominated by White men, who were the political leaders and were responsible for cultural achievements.

This is a legacy that has proved tenacious. Although there is no evidence to suggest that Roman leaders, cultural and political, were uniformly White, classics and ancient history have been associated with whiteness. Many of my students have worried about a lack of representation that works on many levels in the classics. There are few lecturers of colour – that is changing, though much too slowly. But there is also alienation from what is being studied: the Romans are not seen by these students “as people like them”.

The Roman world is seen as white and one in which people of colour had no place or were at the social margins. However, one of the central elements of my teaching is to emphasise the cultural diversities of the ancient Mediterranean peoples and their social distance from contemporary societies and values.

There is a gap here between the likely racial make-up of the Roman population and how that has been understood. This gap, I suggest, derives from a systematic erasure of Black Romans from Roman history. This erasure is similar to the “whitening” of histories and cultures, in which the presence and contribution of Black people is ignored.

Thinking about race in antiquity

Racism is understood as the use of various minor corporeal differences, in particular skin colour, to create categories of people. Those categories are subsequently associated with identities, which reinforce that categorisation. Such categorisation is a peculiar and perverse modern idea.

Greeks and Romans didn’t think in these ways. They were aware of differences. But for Romans, White or Black were not meaningful social categories. As a result, our sources hardly ever mention skin pigmentation, since it wasn’t important to them. It is normally impossible for us to associate particular ancients with those modern racial categories. But this absence of evidence has allowed the assumption that most prominent Romans were, in our terms, White.

However, there is every reason to think that many leading Romans were, in our terms, Black.

Septimius Severus was a Roman general who became emperor in 193 CE. He was born in Leptis Magna in modern Libya. Almost all depictions of Severus are statues or on coins. They show him as having curly short hair and a beard, which is sometimes forked. Such depictions do not represent his skin pigmentation.

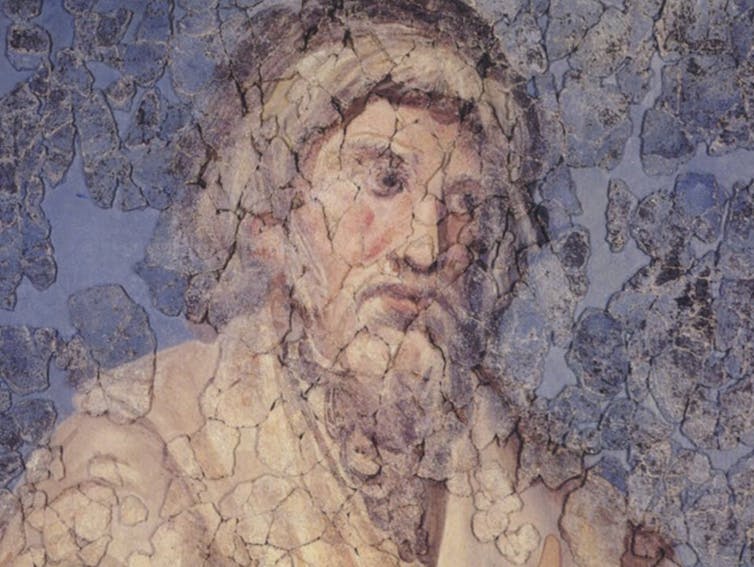

But unusually we have a painting of Severus, the Severan Tondo in the Altes Museum in Berlin. The Tondo shows Severus, Julia Domna, his wife, and their children – the future emperor Caracalla and Geta.

Geta’s face was obscured after his murder by Caracalla. The greying Severus clearly has dark skin. Painted depictions of emperors circulated widely, partly through the military and partly through imperial cult, as we can see in this marvellous bust of Severus himself in the Archaeological Museum at Komotini, Greece. There can be little doubt that this is what people thought Severus and his family looked like. And yet, Severus’ Blackness has historically been questioned.

Roman North Africa

Leptis was a place twice colonised, first by the Phoenicians in the seventh century CE. The Roman colony was formed around the veterans of Legion III Augusta. That legion had served in Africa since its formation in 30 CE.

Although the first generation of soldiers may have been mainly Italian, like all other legions, III Augusta increasingly drew recruits from local communities. The new Roman colony likely enrolled resident locals and certainly the pre-Roman elite.

After centuries of interaction, it is almost impossible to imagine that there were visible differences between the citizens of Leptis and the surrounding African inhabitants. We cannot prove Severus’ skin colour, but it is wrong to assume that he was light-skinned.

Roman Africa was an economic and cultural powerhouse in the later Roman Empire. Goods from Africa circulated throughout the Roman world. One of the first Roman dramatists, Terence, came from Carthage in Tunisia and his appearance is described by the historian Suetonius as fuscus, “dark”.

The second-century CE rhetorician, philosopher and novelist Apuleius was from Madouros, modern M’Daourouch, Algeria. Saint Augustine of Hippo studied in the same town. He and Cyprian of Carthage were major figures in Christian theology. Egypt was a major centre of literary and theological innovation in the late imperial period. Why would we imagine any of these individuals as White?

Empires move people about. The mitochondrial DNA of skeletons in early Roman London showed that Greeks, Syrians and North Africans were among the first Londoners. Africans reached this remotest corner of the Empire. Many Romans were dark-skinned. Yet for moderns, this seems surprising and an assertion that requires justification.

The classical world is a part of our cultural traditions. Colonialism has whitened classics. Such Whitening marginalises Black people. Making Black Romans visible resists colonial mentalities. It embeds Black people in that cultural tradition.

Black Romans were central to Classical culture and not as an exceptional few or as slaves or servants. They were soldiers and traders, dramatists, poets, philosophers, theologians, and emperors. We need to re-imagine imperial Romans as having a completely unsurprising diversity of skin pigmentation.

Richard Alston does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.