A century of incremental progress, colorful characters — and rampant corruption.

As the next Chicago City Council is sworn in Monday, the city enters its 100th year under the 50-ward system with a legislative body representing many more backgrounds and perspectives than it did in 1923 but one that has proven just as prone in recent years to illegal backroom deals.

Thirty-seven of its members have been convicted of crimes since 1973, including former Bridgeport Ald. Patrick Daley Thompson last year — and that’s only the latter half of the modern Council era.

Widespread graft at the turn of the 20th century was a major target of the civic-minded reformers who pushed for the 50-ward system. The Municipal Voters League hoped it “would give independent citizens acting in groups a rare opportunity to clean house,” scholars Peter Colby and Paul Michael Green wrote in a 1979 study on “The Consolidation of Clout” in Chicago.

The city had expanded representation repeatedly after incorporating in 1837, starting with six wards, doubling to 12 and nearly tripling to 35 in the late 1800s, with two aldermen from each ward.

Downsizing from 70 aldermen to 50 “really didn’t put a dent in corruption,” says Dick Simpson, an alderman in the 1970s and longtime University of Illinois at Chicago political science professor who wrote the book on “Rogues, Rebels, And Rubber Stamps: The Politics of the Chicago City Council.”

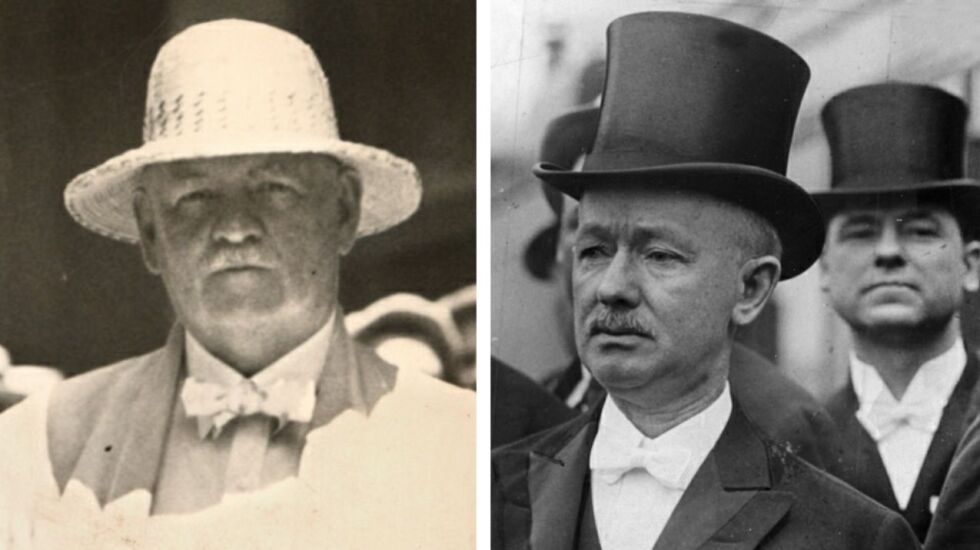

The 1923 reform certainly didn’t deter the greasy-wheeled antics of “Bathhouse” John Coughlin, “Hinky Dink” Mike Kenna and other holdovers from the “Gray Wolves” era, so named by a magazine writer for the silver-haired aldermen known for “the rapacious cunning and greed of their natures.”

“Bathhouse” John famously boasted of turning down a $150,000 bribe, saying he preferred smaller amounts.

“There’s little risk, and in the long run it pays a damned sight more,” the Chicago Daily News quoted him as saying late in his notorious 1st Ward tenure.

He and “Hinky Dink” were long known as the “Lords of the Levee” for the underworld nightlife district they permitted in cahoots with the Chicago Outfit. “Hinky Dink” ceded his ward seat with the 1923 reorganization but won it back after “Bathhouse” John’s death in 1938.

‘Line ‘em up and pass out the bucks’

Party leaders took a more streamlined approach to corruption with the advent of the Chicago Machine, the cogs of which were put in place by Republican Mayor William “Big Bill” Thompson — who scarcely concealed his working relationship with Al Capone — and perfected by Democratic boss Mayor Richard J. Daley.

”Chicago ain’t ready for reform yet,” legendary 43rd Ward Ald. Mathias “Paddy” Bauler gleefully declared to a reporter when Daley beat a would-be reformer in 1955.

The last of the “saloonkeeper” aldermen, Bauler was known for openly talking about what most others considered his ethical lapses, which included paying people for votes.

“We’d line ‘em up and pass out the bucks,” Bauler once told the Sun-Times. “There’d be trouble if we ran out of bucks, but we never did.”

Ethical liabilities aside, former Sun-Times political reporter James Merriner says. “We shouldn’t forget how successful the 50 ward organizations were” under the Democratic Machine, which Merriner examined in his book “Grafters and Goo Goos: Corruption and Reform in Chicago.”

“They were micro-welfare agencies,” Merriner says. “If you needed something, got in trouble, you’d go to the precinct captain or the aldermen, and they took care of it. You get laid off, they help you cover rent. All you had to do was vote for the Machine ticket.”

Daley’s tenure marked a near complete loss of City Council spine, a far cry from the 1940s and early ‘50s, when its members “ran the city government, swung big deals and brooked no nonsense from a subservient executive branch,” Daily News columnist Jay McMullen wrote in 1962.

‘Almost like little mayors’

Instead, Daley — with a massive ward organization that could make or break careers and the patronage jobs to start them — the Council’s “rubber-stamp” era was born, one that has largely persisted. Daley loyalists passed his agenda with nary a second guess from anyone but a few Republicans or progressive stalwart Ald. Leon Despres (5th).

“They put the rubber stamp on [Daley’s] citywide wishes, he left them to control their own wards, almost like little mayors,” Simpson says. “That aldermanic prerogative allowed them much more range for corruption.”

Aldermanic prerogative — the long-held tradition of veto power over any development in an alderperson’s ward — remains the most tempting force toward graft, as outlined in the federal indictment against retiring Ald. Ed Burke, who assumed his 14th Ward seat under the original Boss Daley.

“Did we land the, uh, tuna?” Burke was recorded asking on a federal wiretap late in his record-breaking 54-year Council tenure.

Prosecutors say the metaphorical fish was lucrative legal business from a developer in exchange for his vital assistance in approving their project.

Burke — who has pleaded not guilty to racketeering, bribery and extortion charges — was around for more than half of the Council’s first century with 50 wards, and as its unofficial historian, he’d surely note other milestones for the body.

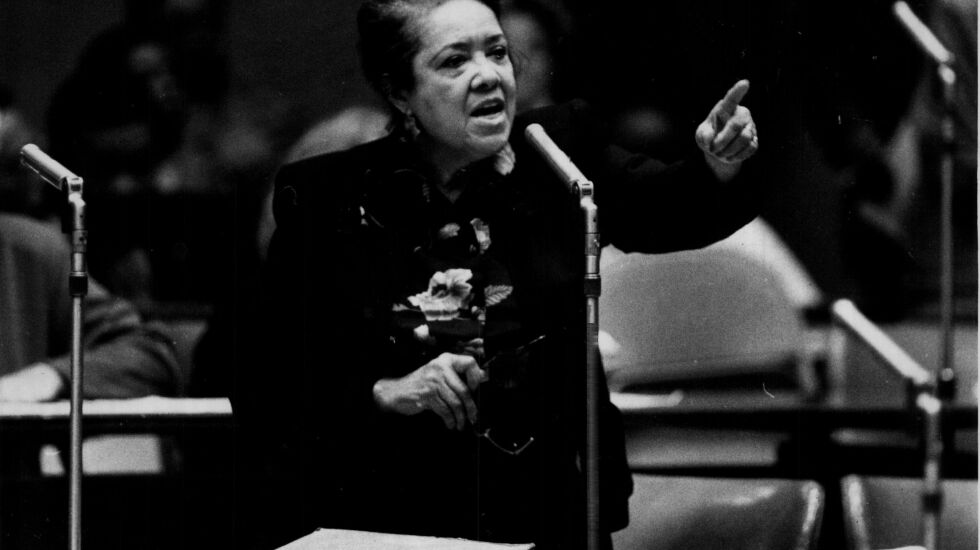

The Council — which saw its first Black member, Ald. Oscar De Priest, elected in 1915 — didn’t break the gender barrier until 1971, when trailblazers Anna Langford and Marilou Hedlund won seats in the 16th and 48th wards.

Their elections prompted infrastructure upgrades to Council chambers on the second floor of City Hall, which had been outfitted with spittoons for generations of tobacco-chomping men — but not with a women’s restroom.

Eighteen women will be sworn in Monday — matching the all-time high set in 2007.

Hedlund, a Daley loyalist, served one term before landing on the Chicago Zoning Board of Appeals and later in Democratic national party leadership.

Langford, who was Black, once hosted the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in her living room to plan a racial integration march on Cicero before she brought her fight for civil rights to Council chambers.

She was knocked out of office after one term but reelected in the 1980s, when she helped pass a gay rights ordinance in 1989 against employment and housing discrimination. Chicago’s first openly gay alderperson, Tom Tunney, wouldn’t take office until 2003.

On Monday, a record nine LGBTQ+ members will be sworn in.

Langford also famously goaded Harold Washington into running for mayor in 1983, flashing some “Langford for Mayor” prints and telling the charismatic congressman she would run if he didn’t.

‘Beirut on the Lake’

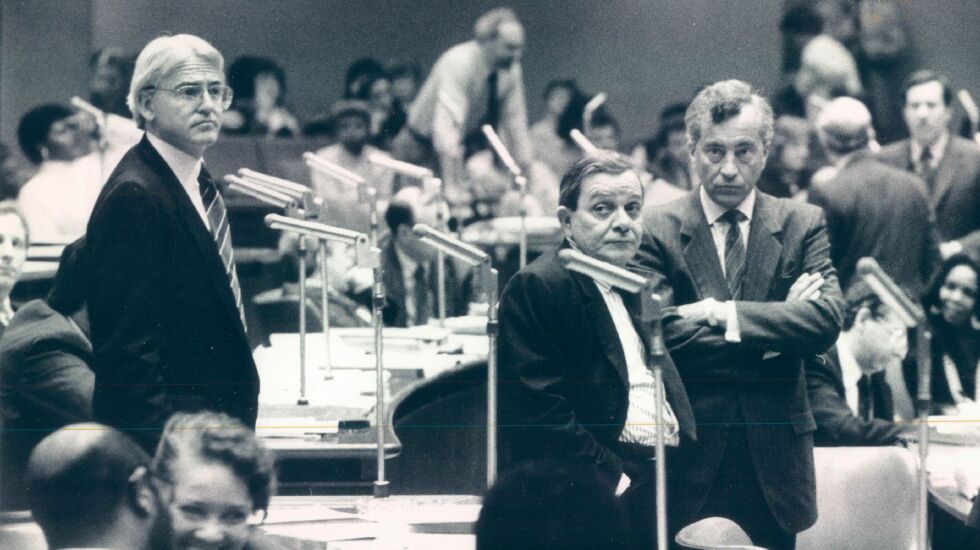

Washington’s “rainbow coalition” win marked a progressive win for Chicago but also ushered in one of City Hall’s ugliest eras: Council Wars. Led by Ald. Edward “Fast Eddie” Vrdolyak and Burke, the nearly all-white “Vrdolyak 29” stymied all of the Black mayor’s agenda and agency appointments in a stark demonstration of this segregated city’s racial politics.

The Wall Street Journal famously dubbed Chicago “Beirut on the Lake.”

“Chicago is always the epitome of American politics,” Simpson says. “During Council Wars, it brought out the most extreme visible cleavages in the nation.”

Washington used executive orders to make strides on public housing and the city budget, according to the Chicago History Museum. But the gridlock wasn’t lifted until a federal court ordered the city to hold special elections in seven wards remapped to better reflect the city’s Black and Latino populations.

Those ward winners cut the “Vrdolyak 29” to 25, giving Washington the tie-breaking vote he needed to advance his agenda until his death in office in 1987.

Washington’s death sparked more turmoil as members of the warring factions battled to appoint his successor. The sessions were so heated that Ald. William C. Henry (24th) wore a bulletproof vest to City Hall.

The Council reverted to its rubber-stamp status under the younger Mayor Richard M. Daley and later Mayor Rahm Emanuel, a period in which corruption continued to fester in several high-profile scandals, perhaps most notably Operation Silver Shovel in the 1990s. The FBI probe ended with six alderpersons indicted, found to be on the take for letting a debris-hauler dump asphalt and concrete waste in protected areas of their wards.

‘This is a total s—- show’

Sweeping corruption investigations, including the one leading to charges against Burke, have continued well into the 21st century, as the Council has been faced with new challenges — and shown hints of an emboldened attitude.

The COVID-19 pandemic sent it into uncharted territory with the first in a series of virtual meetings in 2020. Chaos ensued for a legislative body that was quickly revealed as less than technologically proficient.

“This is a total s--- show,” former 10th Ward Ald. Susan Sadlowski Garza said as the e-meeting devolved into chaos amidst a tangle of hot mics, misdirected replies and general confusion as to “what the f--- they’re voting on,” as one unidentified member put it.

The Council asserted at least some of its independence under Mayor Lori Lightfoot, with a rejection of one of her committee chair picks and pushback against budget proposals, among other rare shows of defiance.

Simpson expects that loosening of the rubber-stamp label to continue under Mayor Brandon Johnson, who supported Council independence on the campaign trail but still foiled a lame-duck power grab by several members to name their own committee heads before his inauguration.

And while some have long been calling for downsizing the Council in line with other major cities, such as New York City — which has 51 council members for triple the population — Merriner suggests that Chicago ain’t ready for that kind of reform.

“A smaller number of wards would be more efficient,” he says. “But is that really the goal of the Chicago City Council?”