Concerns are being expressed over low returns as the census budget potentially leaps to $300 million. David Williams reports

Raw census figures released to Newsroom are setting off alarm bells for one academic.

Officially, census day was March 7 but some early field collections were disrupted by Cyclone Gabrielle, the damage from which prompted the Government to declare a national emergency in six North Island regions.

(Face-to-face visits were delayed in some areas, and the statistics department, Stats NZ, has asked for $37 million extra to cover extra costs. More on that later.)

READ MORE: * Trust in census a big issue, survey suggests * Govt to consider deferring $259m census due to Cyclone Gabrielle

On Friday last week, Stats NZ trumpeted in a press statement that four million people had returned their individual forms. “We didn’t hit this milestone until April 30 in the 2018 Census,” deputy government statistician Simon Mason said.

(Given the debacle five years ago, that’s not a surprise.)

Still, one-in-five people haven’t completed their forms this year. For people of Māori and Pacific descent, that figure is two-in-five.

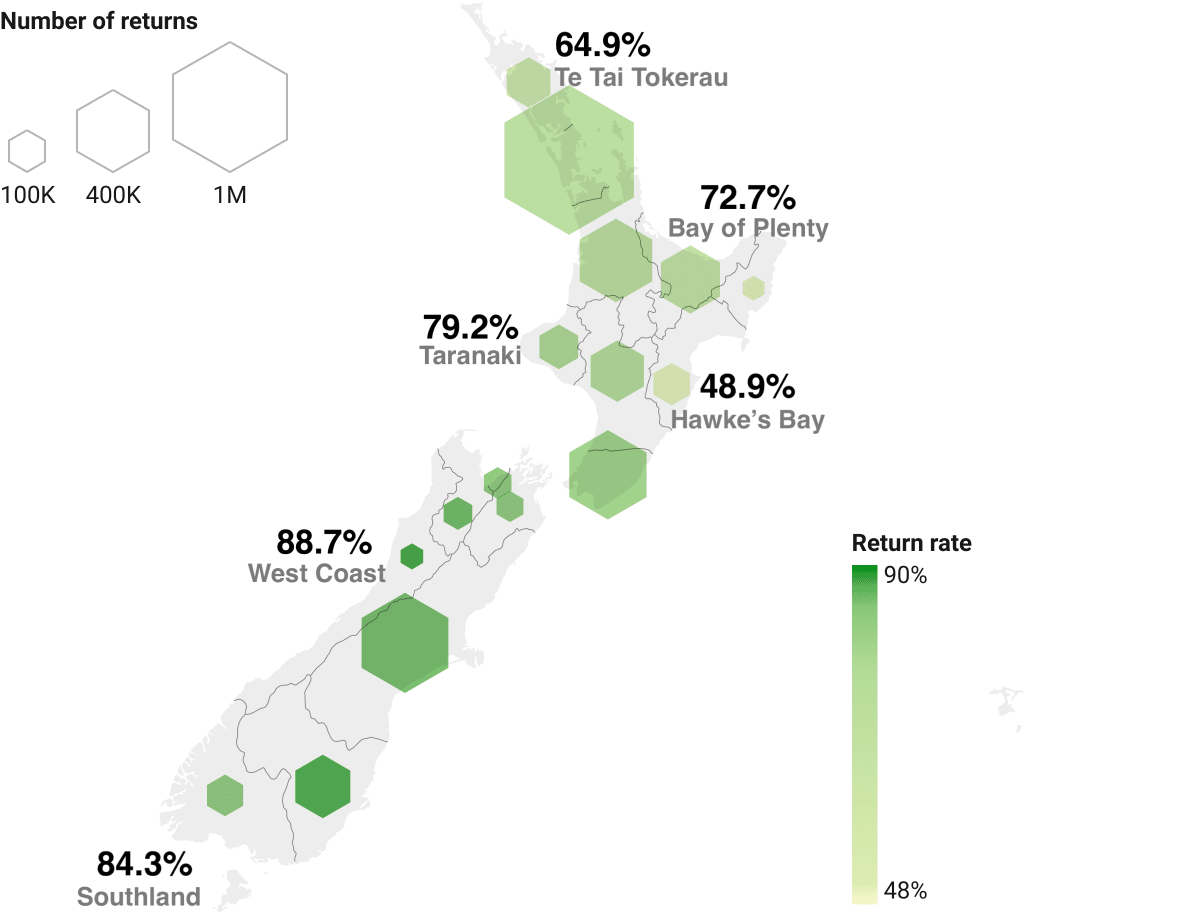

To be fair, field operations only started in Gisborne and Hawkes Bay on Monday. Indeed, raw census return figures released by Stats NZ show extremely low rates in those regions. But it’s the low returns in North Island urban centres that’s raising eyebrows.

“We’re over three weeks after the census now, and I would really expect these indicative rates to be a lot higher,” says Tahu Kukutai (Ngāti Tīpā), a professor of demography at University of Waikato’s Te Ngira Institute for Population Research.

“Having looked at the data for the number of returns, regionally, and broken by Māori descent, and Māori ethnicity, if I was Stats NZ I would be very concerned – even though these aren’t official figures, and even though we wouldn’t get the gold-standard information on response rates until after the post-enumeration survey.”

The survey is undertaken to check the accuracy of the census, after which the official response rate can be determined.

Stats NZ says it is working to lift responses around the country. It has more than 3000 collectors in the field, who will be in communities until at least May 3, and until June 1 in Hawkes Bay and Te Tairāwhiti.

“This phase of the census is by its nature the most complex and difficult to deliver,” says Mason, the Stats NZ executive in charge of census and collection operations. “Focused support for Māori and other respondents yet to take part in the census is the focus of the next period.”

However, he admits “census returns at this point are not as high as they could have been”.

Stats NZ has already fallen behind at least one of its targets, which was to visit all non-responding and partially responding households by nine days after March 7.

Mason says as of Friday last week, about 29,000 dwellings – excepting Te Mana Whakatipu areas, and Hawkes Bay and Te Tairāwhiti – hadn’t received a first visit.

“To date we have made over 1.3 million non-response follow-up visits to over 790,000 dwellings. We are averaging 55,000 visits per day.”

Despite all those efforts, Kukutai says the proportion of individual forms being returned “to me, is concerningly low”. “That is especially the case for the Māori ethnicity returns and the Māori descent returns.”

Low returns might be expected in Northland, Gisborne and Hawkes Bay, Kukutai says, but the raw figures for Auckland and Waikato are, loosely, 77 percent and 76 percent of the estimated population.

“That’s very low. If you took the Māori population for Auckland and Waikato they would be lower still, because that’s total population.

“Even taking account of the severity of regional impacts and devastation [from the cyclone] it’s still low.”

The individual returns figures provided to Newsroom are heavily caveated.

They are raw data and not official figures, Stats NZ’s explanation says. “These figures include duplicates, overseas visitor returns, and should not be used to make any decisions.”

Thousands of returns – 19,200 to be exact – are yet to be assigned to a region.

Māori data is essential, Kukutai says.

It has constitutional implications, given it’s an essential input into the calculation of Māori electoral seats. There’s also a responsibility, under Te Tiriti, the Treaty of Waitangi, to collect iwi affiliation data.

“Ethnicity is a crucial public policy variable here,” the professor says.

Māori descent, based on genealogy or biology, has a “flat classification” – Yes, no, or don’t know, whereas affiliation figures are used to estimate iwi populations.

Despite this importance, the botched 2018 Census had significantly lower response rates for Māori and Pasifika.

The following year, Stats NZ announced it wouldn’t publish official iwi figures due to missing data and a lack of alternative government data sources to fill the gaps.

The statistics department has been increasingly exploring the use of administrative data, from a colossal trove of information called Integrated Data Infrastructure, as an alternative to field collections. Last year, in an “experimental section” of its website, Stats NZ produced an “administrative population census”, which, it warns, is “not official statistics”.

It was discovered in the post-survey analysis that Māori were undercounted by up to 49,200 in the 2013 Census.

“This is information that must be collected, and it needs to be high quality,” Kukutai says.

Of this year’s raw data, she says: “I’m not convinced, particularly for iwi affiliation and Māori descent, that Stats NZ has really done its homework in terms of looking at future-proofed systems that are going to enable that data to be collected in a high-quality way, and in a way that’s actually acceptable to Te Ao Māori, and whether it has the [appropriate] level of oversight and governance.

“It actually should rest with Māori.”

Kukutai gives Stats NZ credit for “learning from the horror show that was 2018”.

There’s Māori representation on the census programme board, Stats NZ has partnerships in Māori communities, and there’s a pilot programme, Te Mana Whakatipu, for iwi-led field operations.

But in a world where statistics offices worldwide are suffering declining response rates, and with high levels of mistrust and disinformation, a more flexible, dynamic approach is needed, the Waikato University professor says.

“One where the community is much more involved, feel like they have a level of oversight, feel like they’re getting the direct benefits from all the data that’s been collected, have some sense of surety that the data that’s been collected is the right information for the right purposes.”

$37m extra sought

Mason, the Stats NZ deputy chief executive, confirms Stats NZ has sought approval from Cabinet for a further $36.67 million to deliver the cyclone-affected census.

That’s interesting language considering a statement made by government statistician Mark Sowden on February 27: “Cabinet agreed today to funding an extension and amendments to the census operation ... in areas impacted by Cyclone Gabrielle.”

The extra money would pay field collectors, and go towards extra marketing and public engagement, and continue paying contracts for operations, like call centres, the website, and recruitment.

Assuming the request is approved by Cabinet, the total budget for the census will sit around $300 million, more than double the $126 million census in 2018.

This raises a few points.

Given the chasm between the two figures, it’s further evidence the previous census was grossly underfunded. It was a disaster waiting to happen – and it did.

As to this year’s iteration, if this enormously expensive survey doesn’t lead to quality data, especially when it comes to Māori, it shakes the foundations of how we’re conducting the census.

A key indicator for this year’s census is a 90 percent response rate for the total population, and a 90 percent goal for Māori responses.

“$300 million is a huge amount of money,” Kukutai says.

“Ultimately, the ability to justify that amount of money being spent in the face of globally declining response rates, is going to be increasingly hard.”

Kukutai is trying to keep an open mind about Stats NZ being able to turn this year’s census returns around. “Time will tell.”

Her concern is what happens if, once again, things go wrong because, as she says, the impacts are never equitable. “The impacts on Māori data quality can be really profound.”