The name’s Bond. James Bond. At least, that’s what it is in the most recent edition of Casino Royale. In five years’ time… who’s to say?

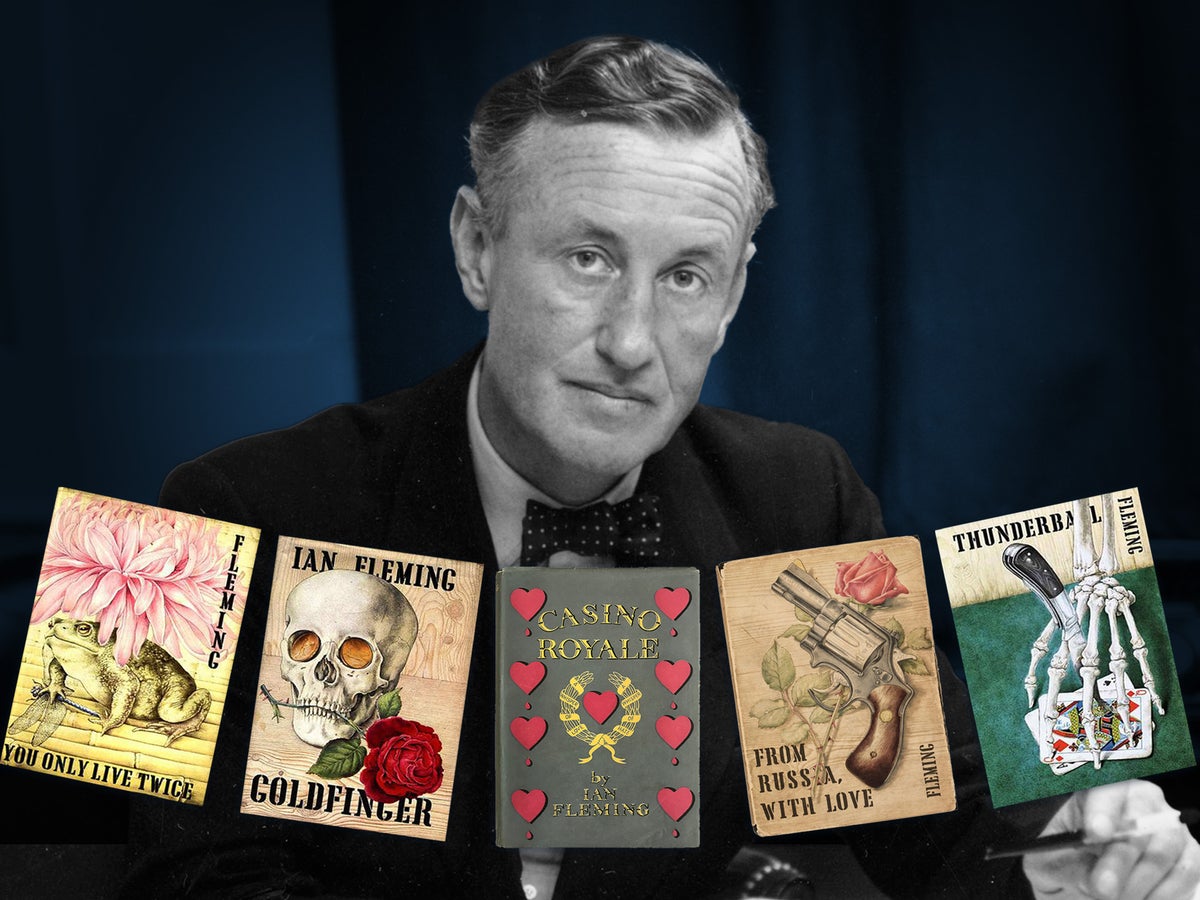

Over the weekend, it was announced that Ian Fleming’s hit spy novels were being republished with a plethora of changes to the language, following a review by sensitivity readers. Many of the changes concerned racist language, with numerous racial slurs cut entirely. Other material, including derogatory remarks about Asians and an appalling reference to “the sweet tang of rape”, were not censored. The news came just days after The Telegraph reported that Roald Dahl’s children’s books were being reprinted with a raft of sensitivity-related amendments. In both instances, uproar predictably ensued.

While “culture war” issues such as this are typically split along rigid left- and right-wing party lines, opprobrium stampeded the publishers from both aisles (as well as a fair number of people applauding the move). There is more to this issue than simply free speech – the matter of whether children (or adults) should be exposed to offensive language. Artists have a right to the creative integrity of their work, even when the work is disagreeable; Dahl and Fleming, both long dead, are unable to consent to the changes. There is an argument to be made that softening the unpleasant edges of these books is an act of erasure, or even historical denialism. Consider, in contrast, the disclaimer that Warner Bros has long shown before outdated episodes of Looney Tunes, which ends: “While these cartoons do not represent today’s society, they are being presented as they were originally created, because to do otherwise would be the same as claiming these prejudices never existed.”

Muddying the issue further is the rather inexplicable metric used to determine what is and isn’t suitable for republication. Even those in favour of censoring books for reasons of sensitivity will likely be left frowning at the limp, artless prose amendments – and, in Fleming’s case, by the baffling inconsistencies when it comes to what offensive material will actually be permitted. Some parts are taken out, other instances left in; some of the racism and misogyny is so inextricably woven into the storylines that censoring is impossible. A cynical mind might also question the timing of the Bond news, just days after the Dahl revelations provoked frantic online consternation. You could hardly contrive a more high-profile marketing campaign than this; the announcement of a new unamended “Roald Dahl Classic Collection” is about as lucrative an act of appeasement as they come.

More than this, however, the decision to rewrite passages from Fleming and Dahl’s work attests to a complete unwillingness to engage with problematic art on its own terms. Dahl’s bigotry is not some disposable accoutrement to his writing; it is part of his holistic worldview, something that both informs and contradicts other parts of his work. His books are lauded for their dark and misanthropic stories. Why do we cherish them? What does that say about us? De-fanging his writing of offensive material promises to absolve the reader of these sorts of questions. In the modern era, a piece of art must not simply be good; it must also be morally upright and unproblematic. Art doesn’t work this way. It never has.

Of course, refusing to censor decades-old books does not mean that we must blithely embrace old prejudices. There are myriad ways in which stories can be altered or updated to cater to modern audiences without compromising their substance. It can be something as simple as a parent omitting a slur when reading their child The Twits aloud. Content warnings are a prudent and non-invasive way of mitigating offence. Another way can be found in adaptation. Fleming’s James Bond, for example – a repellent bigot in the written word – has been increasingly sanitised onscreen, inching away from the racism and misogyny that once defined the character. (The very real prospect of a Black actor taking over the 007 mantle from Daniel Craig would represent a nail in the coffin of Fleming’s regressive politics.)

Not all modern adaptations are so conscious of changing times, however. The recent Matilda musical film embraced Dahl’s noxious classism with delight, with Stephen Graham and Andrea Riseborough’s Mr and Mrs Wormwood depicted as anti-intellectual working-class grotesques. In an otherwise positive review of the film for The Independent, Clarisse Loughrey notes that Matilda the Musical “does not interrogate Dahl’s novel, despite the fact that there are grounds for questions”. Robert Zemeckis’s 2020 version of The Witches, meanwhile, barely updated the antisemitic coding of the original book.

For many people, it is a scary idea – that art can still have something to teach us even if it is problematic. That art, like life, is messy and contradictory and imperfect. It is obvious why a publisher would be inclined to censor these novels. There’s profit in palatability: “cancel-proofing” outdated novels is a way for literary estates to continue lining their pockets in perpetuity. But there’s no honesty to it. In paving over the problematic parts of Dahl’s work, or Fleming’s, publishers are stifling the very questions that are most important to ask: what are these novels actually saying about the world? And should we keep returning to them? Perhaps they are terrified of the answers.