The federal government is on pace to borrow $116 trillion over the next 30 years, and merely paying the interest costs on the accumulated national debt will require a staggering 35 percent of annual federal revenue by the end of that time frame.

And that's likely an optimistic scenario.

Those sobering figures were published Wednesday by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) as part of the number-crunching agency's new long-term budget outlook. The report once again points to an unsustainable fiscal trajectory driven by a federal government that's addicted to borrowing—even as it becomes readily apparent that the bill is coming due.

"Such high and rising debt would have significant economic and financial consequences," the CBO warns. Among other things, the mountain of debt will "slow economic growth, drive up interest payments to foreign holders of U.S. debt, elevate the risk of a fiscal crisis, increase the likelihood of other adverse effects that could occur more gradually, and make the nation's fiscal position more vulnerable to an increase in interest rates."

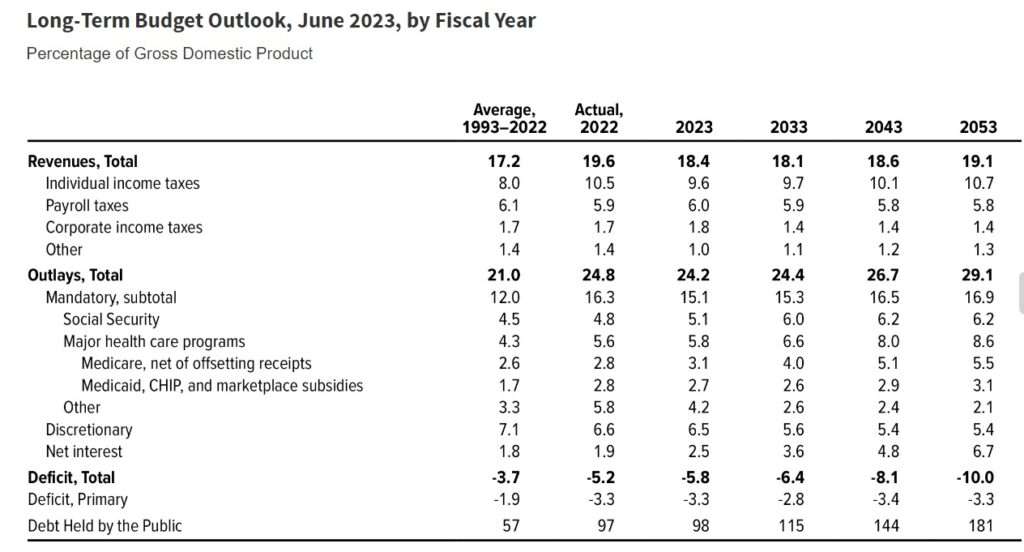

The formula for massive deficits and unsustainable levels of borrowing is actually pretty simple: federal spending that far exceeds what the government collects in tax revenue. Over the past 30 years, federal spending has averaged 21 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), a rough measure of the size of the whole American economy, while tax revenue has averaged 17.2 percent, the CBO notes. That's not great, but the future looks much worse. By 2053, the CBO expects federal spending to grow to 29.1 percent of GDP, while revenue climbs to just 19.1 percent.

Entitlements are the main driver of that future spending surge. Social Security spending will rise from about 5 percent of GDP to about 6.2 percent over the next 30 years. Costs for Medicare and Medicaid will jump from 5.8 percent of GDP to 8.6 percent by 2053.

Financing the national debt itself will become a major share of federal spending in the next few decades. The CBO projects that interest payments on the debt will cost $71 trillion over the next 30 years and will consume more than one-third of all federal revenue by the 2050s.

"America's fiscal outlook is more dangerous and daunting than ever, threatening our economy and the next generation," Michael A. Peterson, CEO of the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, which advocates for fiscal responsibility, said in a statement. The group responded to the new CBO report by renewing its calls for a bipartisan fiscal commission to consider plans for stabilizing the debt.

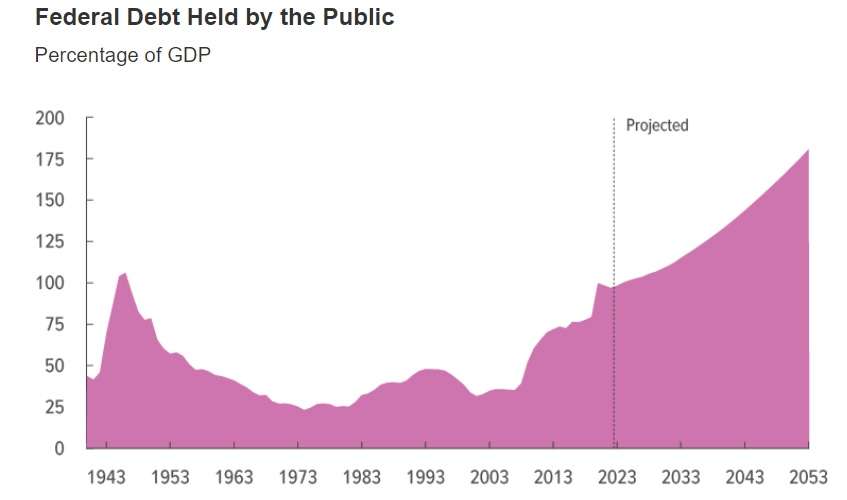

As a share of GDP, the national debt reached a record high of 106 percent during World War II. The CBO projects the record to be broken in 2029, and the debt will keep climbing—to 181 percent of GDP by 2053.

The CBO bases these projections on current law, which suggests this might actually be a rosy scenario. Obviously, the CBO cannot account for new future spending or tax cuts that might be financed by borrowing, and it does not include the possibility of another national emergency like the COVID-19 pandemic that could serve as an impetus to borrow heavily on a temporary basis. But the projections also leave out other things, like the possibility that Congress will extend the Trump administration's tax cuts past their planned expiration in 2025—which would add to the deficit and require more borrowing in the future—or the possibility that Social Security's impending insolvency will be papered over with yet more borrowing. And do you really believe that no Congress or president will hike spending without offsetting tax increases in the next three decades?

Under an alternative scenario in which the Trump administration's tax cuts are extended and federal spending grows at the same rate as the economy (rather than in line with inflation, as the CBO assumes), the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projects the debt to hit 222 percent of GDP by 2053.

There's one shred of good news inside the CBO's latest report, however. Compared to last year, long-term borrowing is expected to be slightly lower. That's the result of the debt ceiling deal struck last month between Congress and the White House. The deal included spending caps on nondefense discretionary spending for the next two years, and even that very limited bit of fiscal responsibility can have a measurable impact on future deficits.

Still, the modest decline in future deficits mostly serves to illustrate the daunting size of the federal government's debt problem. By 2053, the debt will more than double the size of America's economy—and, again, that's only if you assume borrowing won't increase for any reason in the next three decades.

"This level of debt would be truly unprecedented," said Maya MacGuineas, president of the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, in a statement. "Time is of the essence; we simply cannot afford to keep borrowing at this unsustainable rate."

The post CBO Projects Huge Deficits, $116 Trillion in New Borrowing Over the Next 30 Years appeared first on Reason.com.