If Robert Krankvich could ask a question of the Rev. Richard McGrath, the Catholic priest who Krankvich says raped him when he was a student at Providence Catholic High School in New Lenox in the 1990s, it would be: “Why? Why me?”

The Augustinian Catholic religious order that McGrath belongs to and the school it runs that’s owned by the Diocese of Joliet has reached a $2 million settlement on the eve of a trial over a lawsuit Krankvich filed, lawyers confirmed.

Church officials admitted no wrongdoing in agreeing to the payout to end the civil case.

But records reviewed by the Chicago Sun-Times and interviews by the newspaper show there were warning signs about McGrath.

The diocese — the arm of the church for DuPage and Will counties that brought in the Augustinians to run Providence in the 1980s — has said it is looking at closing or merging numerous parishes and elementary schools, partly over finances. Diocesan officials have declined to say how much money they have spent on settlements and other costs linked to child sex abuse accusations against clergy members and others over the years.

Earlier this year, McGrath was questioned under oath about accusations in the lawsuit that he raped Krankvich. The priest responded that he never engaged in “any unlawful, immoral or sexually improper conduct with any student.”

He also was asked whether he had ever viewed child pornography during the time he was president of Providence. McGrath declined to answer, citing his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination.

Augustinians and secrecy

The Augustinian order, which also runs St. Rita High School on the South Side, remains one of the few prominent Catholic organizations in the Chicago region that still withholds from the public the names of known sex offenders within its ranks, though it says it plans to end such secrecy.

“The Augustinians are committed to being transparent within the bounds of canon and civil law,” the order said in a written statement. “They are presently engaged in the process of preparing a list of those Augustinian friars” with established “allegations of abuse, which will be published within the first quarter of 2024.”

Krankvich said, “My hope is with this case getting resolved, more victims and survivors will have the strength and courage to come forward. Because they’re not alone.”

McGrath couldn’t be reached. His lawyer declined to comment.

A revelation that emerged in the Krankvich case centered on an anonymous letter sent to the Augustinians about McGrath, complaining that he repeatedly massaged students’ shoulders at Providence and made them feel uncomfortable.

The letter apparently came from a Providence parent between 2006 and 2010 and began, “Dear Augustinian provincial, please make Father McGrath stop giving . . . back rubs to the boys at Providence.”

The letter said McGrath “also watches the boys in the weight room and does it there, too.”

“Some other parents want to sue the Augustinians, but I don’t want my son exposed to” a legal process.

The letter writer said the note was being forwarded to Bishop J. Peter Sartain, then in charge of the Joliet diocese.

But there is no evidence that anyone from the diocese, now run by Bishop Ron Hicks, or the order forwarded the complaint to Providence or told McGrath to stop, records show.

Sartain couldn’t be reached. Hicks’ office didn’t respond to a reporter’s questions.

The Rev. Anthony Pizzo, who’s now in charge of Chicago-area Augustinians but wasn’t at the time of those allegations, also was deposed for the lawsuit. Pizzo was asked by Krankvich’s lawyer Marc Pearlman what was done in response to the letter.

“I don’t know,” Pizzo said. “It doesn’t seem to be anything.”

Asked what he would do today if he had received that letter, Pizzo said, “Hypothetically, I would provide the letter” to the high school.

“I can say this, is it inappropriate now? Yes,” Pizzo said about the conduct described in the letter. “However, I also believe in putting it into context. It’s not something I would support in any way. However, back then, I don’t know what Father McGrath’s intentions were . . . just perhaps he may have been affirming the kids, just putting his hands on their shoulders.”

Pearlman said, “We don’t know what the intention of Father McGrath was because nobody asked him, correct?”

That’s correct, Pizzo said.

More accusations

Another Augustinian questioned in the case was the Rev. John Merkelis, who became president at Providence in 2018, shortly after McGrath’s departure. He fielded a strange call around that time from another man who’d attended the school years earlier.

Seeming “agitated,” the man left a voicemail stating the “issue was Father McGrath,” and that he “had rubbed his shoulders” as a student, Merkelis said in his deposition.

After consulting with an attorney representing the order, Merkelis called back the man, who went on what seemed like a “stream of consciousness rant,” saying he had been drinking when he left the message. He told Merkelis, “I don’t want to go anywhere with this. I don’t want any kind of money.”

Around that time the same man called police in New Lenox and said he had been molested by two priests while he was a Providence student years earlier, and that McGrath was one of them, records show.

When investigators followed up with the man, he recanted.

But, according to a police report, he said McGrath would enter the boys’ locker room after football games and “stand at the entrance of the showers” and talk with the students “and stare at the naked boys while they took showers.”

McGrath also “blocked the entrance/exit,” causing “the boys to touch Father McGrath on their way out of the shower area,” the police report said.

Questioned at his deposition about standing by the showers, McGrath said, “I don’t recall doing that.”

Asked about rubbing shoulders, McGrath said, “I don’t recall specifically doing that.”

Regarding other physical contact with students, he said, “We’d hug, Providence hugged.”

McGrath’s ouster from Providence

Merkelis also spoke in his deposition about the incident that led to McGrath being forced out at Providence in December 2017 — and that, once publicized, prompted Krankvich to come forward with his accusations from his earlier time as a student.

McGrath was attending a wrestling match at the school, as he often did. He was sitting in the stands when a female student saw him looking at a photo on his cellphone of what appeared to be a young naked boy, records show.

Horrified, the student reported it to staff, and the complaint landed with Merkelis, who called police.

An officer came to the school and, along with Merkelis, approached McGrath in his office.

“Did you ask Father McGrath to turn over his cellphone?” one of Krankvich’s attorneys asked Merkelis in his deposition.

“I did,” the priest said.

“And what did he say to that?” Merkelis was asked.

“That he would not,” Merkelis said.

The attorney asked, “Did he say why he would not?”

Merkelis said, “He did not.”

A police report says McGrath eventually “stood up and walked out of the office, advising that he needed to get to the theater.”

Merkelis says the phone belonged to the school, not McGrath.

The order’s attorney, Michael Airdo, later spoke with McGrath’s attorney Patrick Reardon about the phone and “was advised . . . that no evidence exists,” the police report says.

The following month, police asked McGrath to come in for an interview, records show. He deferred to Reardon, who said no. When police asked Reardon about McGrath’s cellphone, he “explained that he does not think the cellphone will surface or ever turn up,” police records show.

And it hasn’t.

Deposed for the lawsuit, McGrath asserted his Fifth Amendment right not to answer questions when asked whether he had been looking at child pornography on his phone and whether he destroyed that phone.

He called his current relationship with Merkelis “problematic” because he “brought a policeman to my office in 2017, which started this whole mess.”

Asked what McGrath expected Merkelis to do, McGrath took the Fifth again.

McGrath moves near a Catholic school

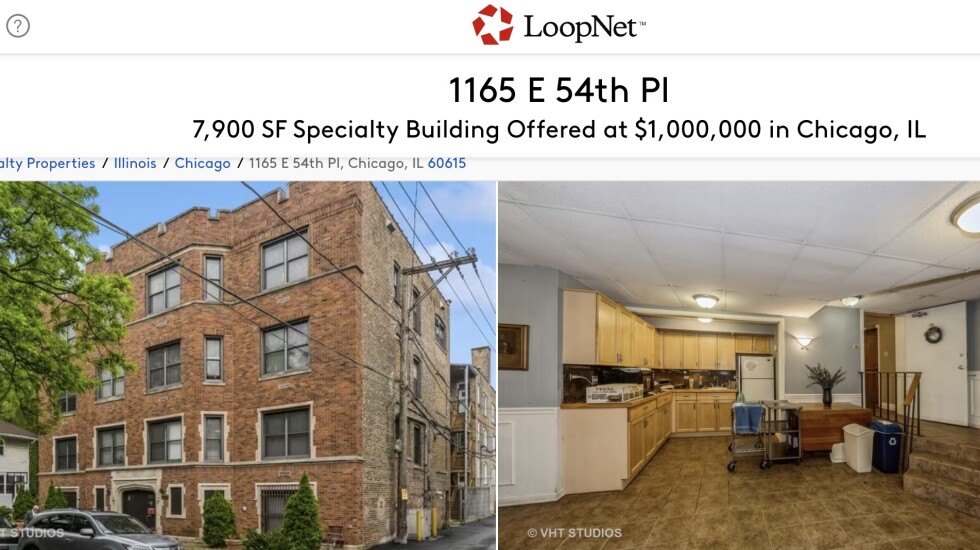

McGrath portrayed his departure from Providence as a forced exit. The order moved him from his longtime residence next to Providence, he said, to a monastery it runs on the South Side near the University of Chicago.

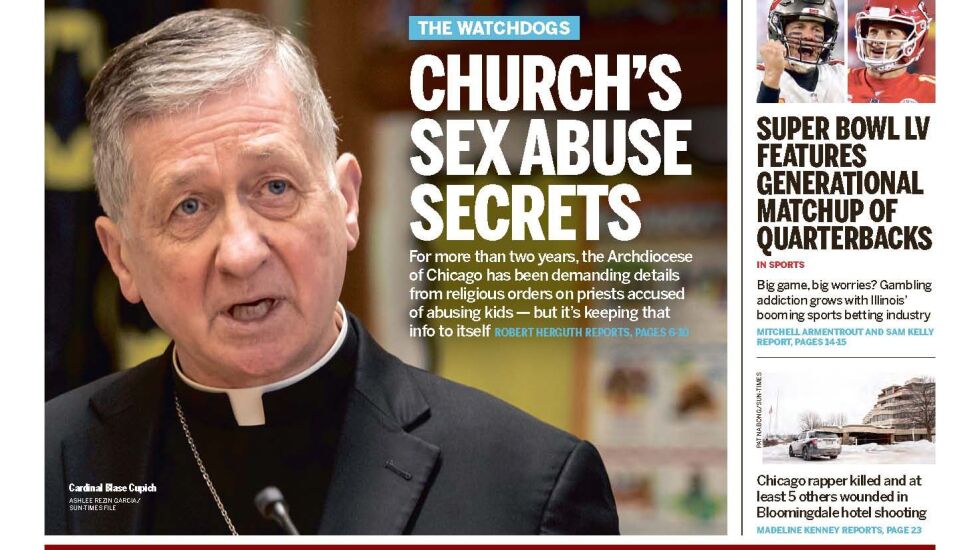

But neither the Augustinians nor the Archdiocese of Chicago, the arm of the church for Cook and Lake counties run by Hicks’ mentor, Cardinal Blase Cupich, told a Catholic school nearby or an adjacent preschool of McGrath’s presence.

After the Chicago Sun-Times reported he was living there, McGrath was sent away.

The South Side monastery was recently put up for sale for $1 million. An Augustinian representative says the McGrath suit didn’t prompt the decision to sell.

It’s unclear how much of the settlement with Krankvich the Augustinians and the Joliet diocese, whose lawyer was involved in defending the lawsuit, each covered and where the money came from.

McGrath said in his deposition that his order next wanted him to move into its complex in Crown Point, Indiana, but that, too, was close to a preschool, so he refused.

He decided to move away from the order, which declared him “illegitimately absent.” Members of the order take vows of poverty, chastity and obedience, and he no longer was obeying his superiors.

This highlighted one of the many inconsistencies that emerged since then, according to records and interviews.

McGrath violated a core aspect of being an Augustinian but wasn’t kicked out — though it appears the order at this point, six years later, is moving toward expulsion, court records show.

Church officials said they weren’t financially supporting him, but they were helping with his “supplemental medical coverage” — while McGrath made money helping around the house of an older former parishioner, he said in his deposition.

McGrath said his order didn’t know where he lives but acknowledged staying in regular touch with a fellow Augustinian priest in Indiana he regards as a close friend and who knows where he lives.

A broader silence

The Augustinians in the Chicago region as yet haven’t made public a list of members linked to sex abuse even as other orders such as the Jesuits, Dominicans and Carmelites have made moves toward greater transparency.

Cardinal Robert Prevost, a Chicago native and Augustinian, once ran the order’s Chicago-based province that covers the Midwest and also served as the international leader of the group, based in Rome, reporting to the pope. Recently, he was elevated by Pope Francis to be one of the top officials at the Vatican, overseeing an office involved in selecting new bishops, a powerful post.

Prevost had the authority to make the order publicly disclose abusers in its ranks, but there’s no evidence he did.

In 2021, a Sun-Times reporter asked Prevost for help in getting answers from his Chicago counterparts. He said, “I’ll see what I can do,” but didn’t respond to follow-up questions.

Pizzo wouldn’t address questions about Prevost not creating public lists, but said, “Nothing is more important to the Augustinians and me than transparency. Years before it became the general law of the church, under the leadership of Fr. Prevost put into place the requirement that there be a set of protocols . . . to guide all members in the different aspects of promoting child protection as well as in responding to cases where accusations might be received.”

As for the settlement, Pizzo said, “We continue to hold all of those involved in this matter in our prayers. . . . There is no higher priority for the Augustinians than the safety and well-being of those entrusted to our care. We have implemented robust child protection policies and procedures intended to ensure the safety of students and to provide a nurturing environment for all to whom we minister.”

Dioceses are geographic arms of the church, led by a bishop. Religious orders generally operate beyond such boundaries, each embracing a particular mission or following in the mold of a saint. In the case of the Augustinians, it’s theologian-philosopher St. Augustine.

Most orders, including the Augustinians, belong to a consortium called the Conference of Major Superiors of Men, which long has recommended that its members be transparent about sex abuse by clergy, in part by publishing lists of known offenders — a step that victims and many church leaders have said acknowledges the suffering inflicted on the abused and can help healing.

Airdo, one of the Augustinians’ lawyers in the Krankvich case, has worked with the major superiors conference, according to his law firm biography.

During depositions for the Krankvich case, he repeatedly told the priests who were being questioned not to answer certain questions.

Pearlman asked Pizzo during his deposition, “As you sit here today, are you aware of any Augustinians who have had established allegations” regarding “sexual misconduct with a minor?”

Airdo interjected, “Objection . . . Father, you will not answer those questions.”

“It’s a yes-or-no question, by the way,” Pearlman said.

“You will not answer those questions,” Airdo told Pizzo.

“Father, are you going to follow counsel’s instruction not to answer that question?” Pearlman asked.

Pizzo said, “Correct.”

Representatives of the Augustinians say some of the questions from Krankvich’s lawyers were irrelevant or not allowed in this setting, so cutting off a line of inquiry was appropriate.

Pearlman disagrees.

Besides McGrath, five Augustinians from the Chicago region are listed by the Bishop Accountability watchdog group as alleged child sex offenders.

Krankvich says he continues to struggle because of the abuse he suffered.

“I’ve had several suicide attempts, and I’m still here,” Krankvich says. “So there’s a guardian angel.”

READ MORE