It was as I folded myself into the tiny cockpit of the Caterham Super Seven 600, that I made my first mistake. Collecting the car from Caterham’s shiny new factory facilities in the London Thameside suburb of Dartford, I weighed up the practicalities of removing the canvas roof for the half an hour journey back home to South London. The sun beat down and I had no sunglasses or hat. Best keep the roof in place.

To the unfamiliar, the cockpit of a Caterham is akin to travelling back in automotive time. This is a world without adornment, fripperies or unnecessary accoutrements. Keeping the roof up would have been all very well in a modern droptop, because they have ventilation systems, perhaps even air conditioning, to counter the effect of sun on black canvas. In the Caterham, not so much. The doors, such as they are, can only be shut or taken off altogether, so there was no opportunity to crank open a window. In place of conventional air vents, the little Super Seven seems to pump heat from the engine directly into the cabin.

Within a few miles, the sweat had started to build up. Whilst hardly tricky to drive, the oppressive climate made getting to know the little car’s foibles and character harder to parse. From the switch-like manual gearchange, ultra-direct unassisted steering and intimidatingly diminutive scale, that first journey was a baptism by fire.

On the next journey, I sensibly opted to remove the roof. This is a convoluted process involved popper fastenings, an internal deckchair-like structure and brute force. To put it back, you reverse the steps, ‘usually in the pouring rain,’ according to Caterham’s cheerful PR rep.

Once topless (the doors remain in place, unless unbolted, and have fixed panel plastic windows), the character of the car is transformed. It’s marginally easier to squeeze into, but at least you can step in and slide down, rather than squeeze through the tiny door opening, but once firmly installed you are engaged not just with the Caterham’s snappy dynamics but also the proximity of the world outside, just grazing the tarmac, eye-level with the wheel nuts on buses and articulated lorries.

This low to the curb, a couple of feet below pedestrians and cyclists, one of the unexpected consequences of Caterham ownership is that you’re unwittingly privy to passing comments and conversations when pulled up at junctions and lights. This was an almost exclusively positive side effect as people offered up an array of questions, compliments and overhead bon mots. Even cyclists seemed to feel some affinity with the spindly little car, perhaps sensing that other, larger road users imperil you just as much as they imperil them.

That was around town. On the open road, life with the Super Seven was never dull, although sometimes it was less than comfortable. A 90-mile jaunt to the country was an opportunity to experience everything from motorways to winding lanes. The former could be a bit of an endurance test, putting the little turbocharged Suzuki 660cc engine through its paces.

This is the smallest petrol engine on the UK market, putting out an incredibly modest 84bhp. However, at a featherweight 440kg (around about the weight of a battery pack in a Tesla Model 3), the power-to-weight ratio allows for zippy acceleration and more than enough speed to keep up with contemporary traffic. It’s not even the smallest and lightest car the company makes. That honour goes the Seven 170, which swaps out the swooping flared front wings of the 600 for over-the-wheel units, and pares everything back to the bare minimum.

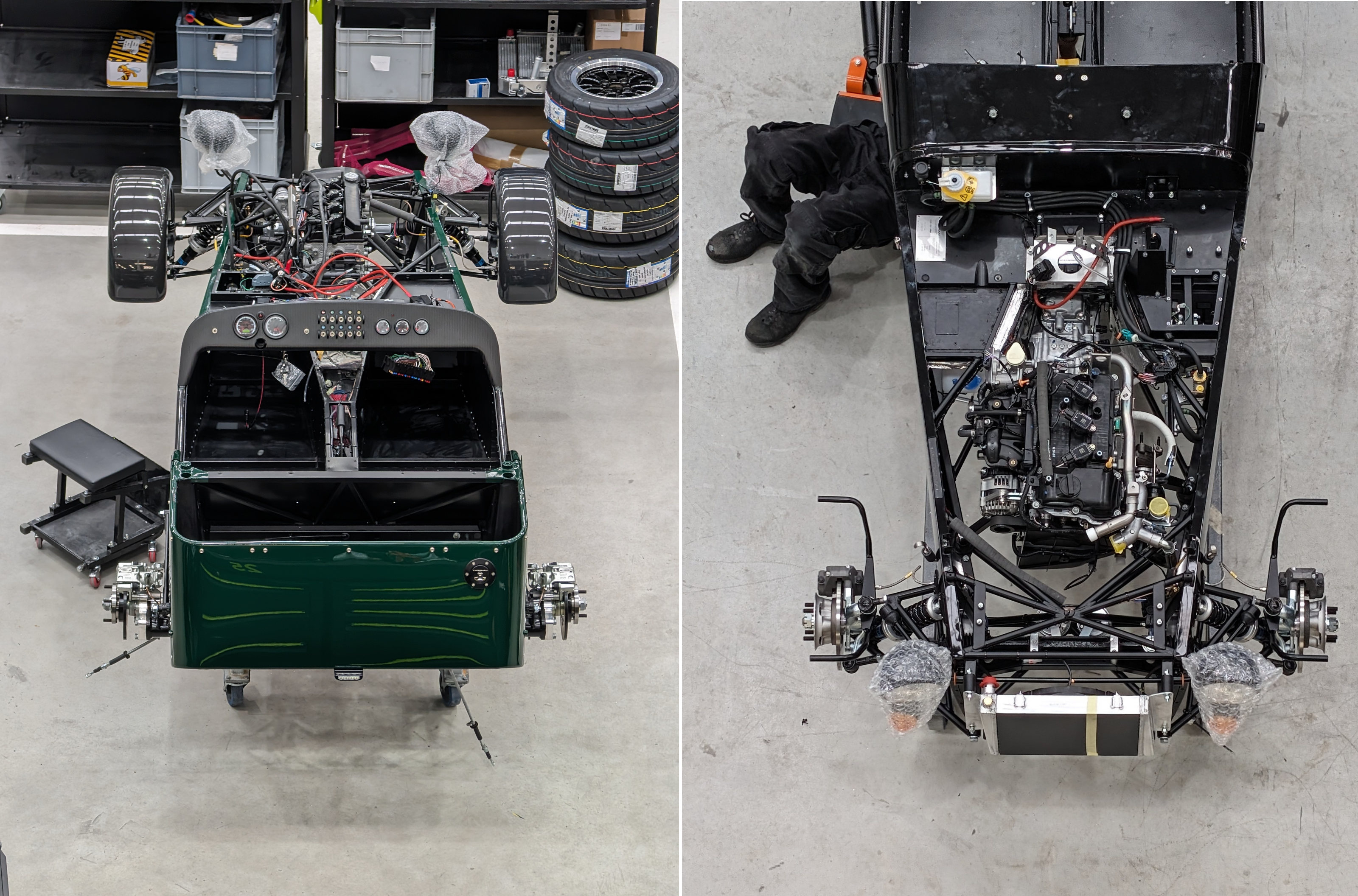

In comparison, the 600 has a very slightly elevated sense of occasion, with design inspiration drawn from the company’s heritage, rather than the spirit of stripped down track driving. The 54,000 square foot Dartford factory is laser focused on this model, taking in increasingly bespoke customer requests. These capabilities were ably demonstrated by the recent RAF Benson Caterham Seven 360R, as well as run-out editions of the Seven 485 CSR. It’s also where you go to get your Caterham race car specified and fettled, part of a long-running single make race series, the Caterham Academy, that acts as an affordable springboard into motorsport.

Not counting additional options, the Japanese-owned company, produces a huge range of cars, including the Seven Academy Car, Seven 170, Super Seven 600, Super Seven 2000, Seven 360, Seven 420, Seven 420 Cup and Seven 620. The current European range consists of the Seven 170, Super Seven 600, Super Seven 2000, Seven 340, and the Seven 485 and Seven 485 CSR Final Editions.

Once you step into the Super Seven 2000 and beyond you’ll be using the tried and tested Ford Duratec engine, a 2.0-litre unit that can be had in various levels of tune, dramatically increasing the power-to-weight ratio. Prices double, as does the perception of speed. The 2.0-litre cars can also be built using Caterham’s ‘Large Chassis’, which increases the width of the car to provide slightly less intimate accommodation for two.

Back to the present. My left side is hot, my right side is cold, the buzzy drone coming from 660cc keeping up with modern traffic is starting to get a little wearing, and then there’s the task of canvas and popper wrestling once you’ve parked up in order to weatherproof the interior. And yet life with this tiny machine has a lot going for it.

The view down the long bonnet to the skinny tyres and round headlights is timeless. The steering communicates instant direction changes, and the engine demands to be revved hard as you switch up and down through the gears. Although I occasionally physically tired of the experience, the joyful spirit never waned, and at the start of each journey, any travails or discomfort were once again re-set to zero.

How long can Caterham go on providing this kind of raw, analogue thrill? Low volume car makers are notoriously susceptible to big shifts in regulation, but also extremely adept at mapping out a legal path to market. Electrification of the Seven’s simple, ultra-light package would change its character irrevocably, possibly losing the allegiance of many whilst welcoming others to the fold. For the short term, the use of Suzuki and Ford engines is assured, but it won’t last for ever.

Caterham is currently experimenting with an EV Seven, as you’d expect, although it’ll take a few more generations of battery refinement before it can be anything close to the featherweight status of the 600. There’s also the much vaunted Caterham Project V, an electric sports car on an altogether different mission to the Seven. If it happens – and Parent company VT Holdings has already set up a separate entity to oversee ongoing development – it’ll need a new factory and facilities.

Should Project V ever come to fruition, the whole ethos of Caterham could change. For now, if you value the synergy between mind, machine and road, there are no better cars than a Super Seven.

Caterham Super Seven 600, from £30,490, CaterhamCars.com, CaterhamCarsLtd