The Milky Way has a 50-50 chance of colliding with a nearby galaxy in the next 10 billion years, a new study finds.

Yet while those odds appear daunting, the new finding suggests the catastrophic collision is far less likely than previously thought.

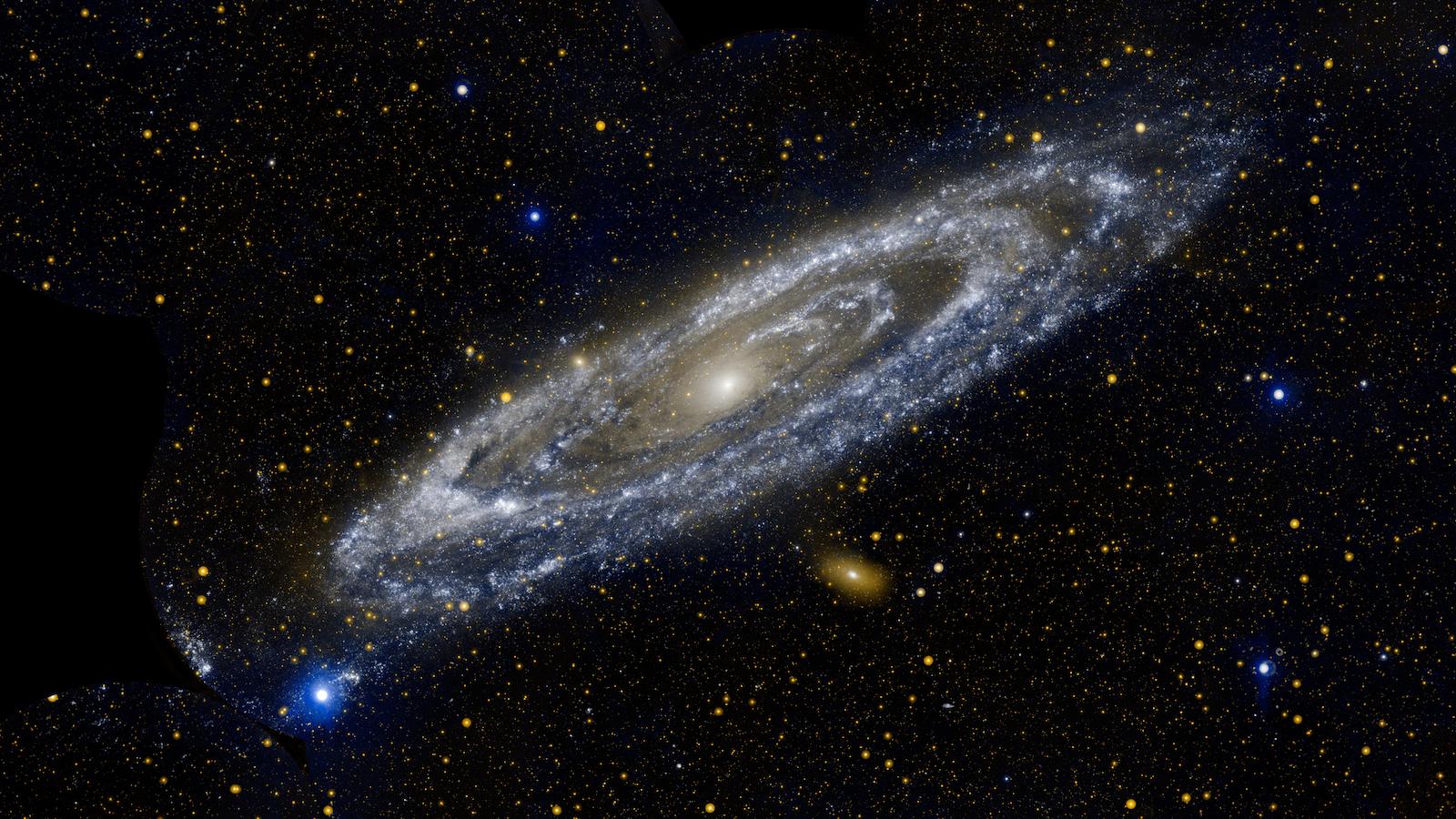

Located roughly 2.5 million light-years away, the Andromeda (M31) galaxy is approaching our Milky Way at a speed of 68 miles per second (110 kilometers per second). Because of this astronomers have long predicted that the two galaxies will inevitably become locked in a fatal dance sometime in the next several billion years — spiraling into each other and merging to form a new galaxy.

But according to a new study, published June 2 in the journal Nature Astronomy, the two galaxies are just as likely to narrowly miss each other.

"[Our galaxy] used to appear destined to merge with Andromeda forming a colossal 'Milkomeda'," co-author Alis Deason, a professor of cosmology at Durham University in the U.K., said in a statement. "Now, there is a chance that we could avoid this fate entirely."

Related: James Webb Telescope spots galaxies from the dawn of time that are so massive they 'shouldn't exist'

American astronomer Vesto Slipher discovered Andromeda galaxy's possible collision course with our own in 1912, when he found that Andromeda's light was doppler-shifted to the blue part of the light spectrum due to its approach.

Further studies predicted that Andromeda's eventual collision with our Milky Way was inevitable within the next 5 billion years — a process that would see our solar system catapulted to an outer arm of the newly merged galaxy.

But, according to the researchers behind the new study, these earlier studies did not take into account a "confounding factor" — the gravitational effects of the other, smaller galaxies inside the Local Group to which the Milky Way and Andromeda belong, which could nudge the galaxies away from a crash altogether.

"We find that uncertainties in the present positions, motions, and masses of all galaxies leave room for drastically different outcomes, and a probability of close to 50% that there is no Milky Way-Andromeda merger during the next 10 billion years," the authors wrote in the study.

The researchers used observations from the Gaia and Hubble space telescopes to get estimates of the masses, movements and gravitational interactions of the four largest Local Group galaxies. They then fed these data into a model that simulated a number of possible scenarios.

With the interactions of the four largest galaxies inside the local group (the Milky Way, Andromeda, the Triangulum galaxy and the Large Magellanic Cloud) taken into account, the researchers found the chances of a Milky Way-Andromeda collision were reduced to a coin flip. And if the merger does occur, it won't be for at least another 8 billion years.

"We find that the next most massive Local Group member galaxies — namely, M33 [Triangulum] and the Large Magellanic Cloud — distinctly and radically affect the Milky Way-Andromeda orbit," they wrote. "Uncertainties in the present positions, motions and masses of all galaxies leave room for drastically different outcomes."

Despite this, the researchers note that their study is far from the final word on a "Milkomeda" merger. To make even better calculations, the scientists are awaiting the release of new data from the recalibrated Gaia space telescope.

"Upcoming Gaia data releases will improve the proper motion constraints and mass models are continuously refined," the researchers wrote. "However, it is clear that galactic eschatology [the study of end days] is still in its infancy and significant work is required before the eventual fate of the Local Group can be predicted with any certainty. As it stands, proclamations of the impending demise of our galaxy appear greatly exaggerated."

Eventually, all of the galaxies within the Local Group will collide and merge, but this process may take many times longer than the universe's present age to occur.

"We see external galaxies often colliding and merging with other galaxies, sometimes producing the equivalent of cosmic fireworks when gas, driven to the centre of the merger remnant, feeds a central black hole emitting an enormous amount of radiation, before irrevocably falling into the hole," co-author Carlos Frenk, a professor of cosmology at Durham University, said in the statement "Until now we thought this was the fate that awaited our Milky Way galaxy. We now know that there is a very good chance that we may avoid that scary destiny."

Editor's note: This story was originally published when the research was a pre-print, and has been updated upon its release as a peer-reviewed article.