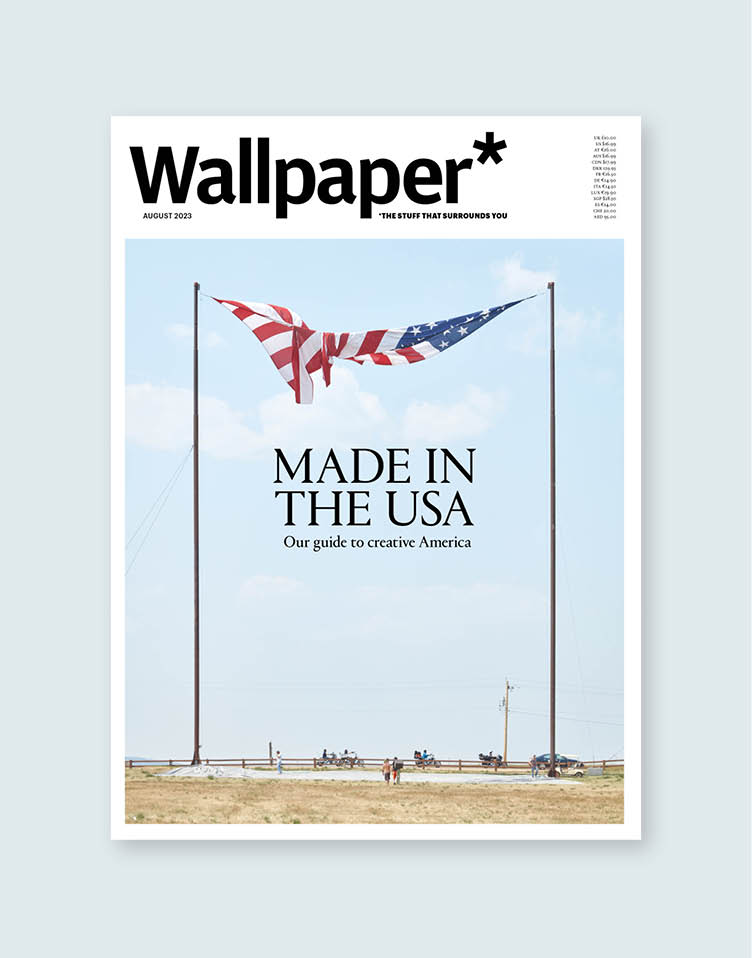

Wallpaper* has always been inspired by collectives, however informal, that lift each other up while remaining grounded along the way. Here, photographer Caroline Tompkins, one-eighth of this (mostly) New York-based cohort of photographer friends – featured in our Wallpaper* USA 300, a guide to creative America and the Wallpaper* August 2023 print issue – shares insights into their past collaborative decade. Read on for the group’s back-and-forth conversation, spanning ‘The American Dream’, romanticism, Craigslist, hurricanes, the realm of possibility, and photographic predecessors.

Caroline Tompkins on life and lensing with friends

A few times a year, we’ll find ourselves in Cape Cod or New Jersey or Maryland in a vacation home of whomever’s parents made the best life choices. In these coastal rooms, the same scenes play out. Molly enters the house and sets up various candles and cheeses by a window. Dave shuffles people together saying, ‘We gotta get a pic of these two!’ Bobby is putting an apple on someone’s head and a softbox as close to their face as possible. Ryan is photographing everything and everyone with a 28mm lens and a Dutch angle. Tim finds an exploded car down the street to photograph at dusk. Chris already took pictures of gas station paraphernalia on the way up. No one really knows what Corey is up to, but he’s getting extremely close to something on the ground. I’m waiting for the sun to set when everything becomes beautiful.

Sometimes we all take pictures of the same thing and other times we all come together to help one person take the photo. Ego is a wonderful servant and a terrible master. These pictures end up in books or Airbnb moodboards or hidden away on hard drives. One man’s photo dump is another man’s Amex campaign.

Most of the time we’re together in New York, but the real bonds are formed in group chats: American Photography School, Juergen Teller Support Group, Payboo Monthly Payments, and so on. These group chats feel like the only place where you can still be critical about photography. We all care about our reputation too badly to be critical anywhere else. It’s also the only place where someone can make the same request for a retoucher recommendation seemingly every week for months on end.

We’ve spent the last ten years letting our individual tides lift our communal boat. We share our lists of editors, our PDF portfolios, our sample estimates, our new books, our rate negotiations, our wins, and our losses. They’re the only people I can count on to tell me when my photos are bad. I remind myself that people pay a lot of money for that. Lately, when I think about who I take pictures for, the truth is that I do it for my friends.

What makes American photography: a collective in conversation

Bobby Doherty to Molly Matalon

BD: If I could explain American photography in one word it would be nostalgia. I think your photos are very nostalgic but at the same time, they're intensely about you. This is what I love about your photos. It's what makes the connection between your portraits and your still lives so fluid. Nostalgia is broad and malleable and you take what is broadly familiar, mix it with bits of your own soul, and create photos that are unmistakably Molly. You grew up in Florida, which has a very recognisable aesthetic. I see flashes of your childhood in your photos and I want to know what, if any, specific scene from your childhood you are chasing in your photographs.

MM: In Florida, everything would shut down during hurricanes. There was no school for days and our windows boarded up with wood. My brother and I would sit in the garage with the door up after the storm passed. Making little ecosystems in plastic tubs, collecting things for critters. When thinking of the broad familiarity you’re talking about, I think of still life. There’s a connection for me in this memory about foraging, making an arrangement, and photographing it. But I have so few childhood memories that are true scenes. Couldn't tell ya if the hurricane story is real even. Maybe that’s why my pictures feel like I’m chasing something that doesn’t exist.

Molly Matalon to David Brandon Geeting

MM: Dave, so much of what I perceive you to be doing with photography is building little fantasy world vignettes, which I don’t particularly frame as an American practice but it does make me think about ‘The American Dream’. I wonder if you think about aspiration when you are making pictures, in the sense of something that’s not possible but you wish was, or do you consider your pictures to be more of a subversion of ‘The American Dream’ in the sense of, ‘there’s no way it's possible to achieve that, so I made this’? And if so, could you explain your thinking around either?

DBG: I've always been enticed by this idea of ‘Fake It ’Til You Make It’, which seems similar to ‘The American Dream’ in a sense. It doesn't matter if my photographs are actual slices of life or assembled in a studio, as long as each image is successful in evoking a feeling. A lot of what I do may be read as ‘subversion’, but I'm most interested in the realm of possibility. Most nights, around 1am, I begin to feel my mind lose interest in the neuroticism of the previous day and embrace the warmth of future possibilities. If there is ‘no possible way’ for me to go to Antarctica tomorrow to make a photograph, I'm just as happy – if not happier – to print out a giant stock image of Antarctica and stage a scene instead. Reality is what you make it.

David Brandon Geeting to Timothy O’Connell

DB: When I think of your particular predecessors, names like Robert Frank, Lee Friedlander, Garry Winogrand, and William Eggleston come to mind. But the strength of your pictures, for me, is that they feel more reckless, less precious, and strike a balance between being quite beautiful and also rather haunting. Even though your images are pulled from reality, they feel less like ‘documentation’ of this world and more like a glimpse into the world of your mind. That said, do you consider your work to be ‘documentary’, following in the footsteps of that rich history? Or how would you describe what you're doing?

TO: I don’t consider my work to be documentary. My work is heavily influenced by the documentary aesthetic, yet, like Eggleston, Frank, and Friedlander, it lacks any definitive truths. My work is an exploration into the complex and nuanced notions of culture.

Timothy O’Connell to Caroline Tompkins

TO: How did growing up in the Midwest, or more specifically Ohio, influence your interest in intimacy and sexuality?

CT: I often felt like I was experiencing parallel Ohios. The Ohio in my parents' house had books and VHS tapes on how to have better sex. I would look at the diagrams of dicks in locked bathrooms and hide the tapes under my bed. I feel grateful to have my first porn experience be an instructional video on how to go down your wife.

Then there was the other Ohio. The one with 60ft Jesus statues erected off the side of the highway and no-touching requirements at emo bands’ concerts. I think I’ve always liked being a spy.

Caroline Tompkins to Chris Maggio

CT: I don’t see you as someone who has direct ‘photographic parents’, but instead referencing photography as a medium that’s used in various contexts. I’m curious what contexts of photography are interesting to you right now?

CM: The most exciting photographic contexts are the strange little pictures that we don’t necessarily think of as ‘Photography’ in our everyday lives: compressed pictures from Craigslist ads, vacation snapshots uploaded upside-down to Facebook, an eerie picture of someone’s dinner on Yelp. I’m inspired by the accidents and mysteries that arise in photos when we’re not totally paying attention, and these last bits of photographic detritus are thrilling because they’re the least curated. They tell better stories – some more intentionally than others.

Chris Maggio to Ryan Lowry

CM: For me, there’s a real bolt of romanticism in your photos that’s often pierced by something brash: a composition of extremes, the camera flash straddling the line of proper exposure, things punctuating the frame in the foreground… how much of that has to do with how you think the US should be portrayed photographically? Is it something of a mix of sincerity and irony? Are those ideas mutually exclusive?

RL: When I am photographing, I’m really trying to enter that headspace where I am absorbing my environment and letting my subconscious translate for me – seeing what's in front of me and letting whatever is floating around back there in my brain influence my decision making, so naturally if I am photographing in the US, my views get extracted in the process. I am sort of hyper-sincere but also looking for the humour or ironies in everything – a picture of an apocalyptic sky with some bizarre use of flash while you can see that I am out walking my dog… Surely that says something about America?

Ryan Lowry to Corey Olsen

RL: So I suppose this is sort of a statement backed with a question… I believe that our experiences growing up – and specifically what we become interested in during our adolescence – becomes burned into our subconscious and informs the way we dress, our living spaces, or more importantly to this conversation, our aesthetic decisions / the choices we make when we look through a camera. You were born on Long Island and then grew up in rural Maine – there are many American experiences but I think this one, specifically, is uniquely American; what about your upbringing and class background influences your work today? What about your interests as a teenager are present in the way you see the world today?

CO: Growing up in Maine, I spent a lot of time exploring nature. I was one of those kids playing with a ladybug or dandelion in the outfield during a baseball game. I feel like that relates to when I was making my body of work Garage Still Lifes, where I made still lifes with stuff from my childhood garage and my mom’s boyfriend came in to smoke and was like, ‘I don’t know why you’re taking photos of that old gas can… wouldn’t photographing girls in bikinis lead to more success?’

As a teenager, I felt a bit isolated in Maine. But I spent my time going to punk shows in basements. I appreciated the unapologetic expression and supportive community. Being yourself, pursuing your interests and creativity with passion no matter what. Might sound corny but this is how I define punk and it’s how I still try to approach my work today.

Corey Olsen to Bobby Doherty

CO: I think you have the highest output of photo-making in our friend group – do you think that’s an American influence?

BD: I think I take a lot of photos because I'm not worried about making bad photos. I think you have to take 10,000 bad photos before you get a good one. I guess it's stereotypically American to choose action over inspection.

A version of this article features in the August 2023 ‘Made in America’ issue of Wallpaper*, on sale 6 July, available in print, on the Wallpaper* app on Apple iOS, and to subscribers of Apple News +. Subscribe to Wallpaper* today